Turning to the Light: Paula Wilson Interviewed by Heidi Howard

Works that blend ecology and eroticism.

Oct 24, 2022

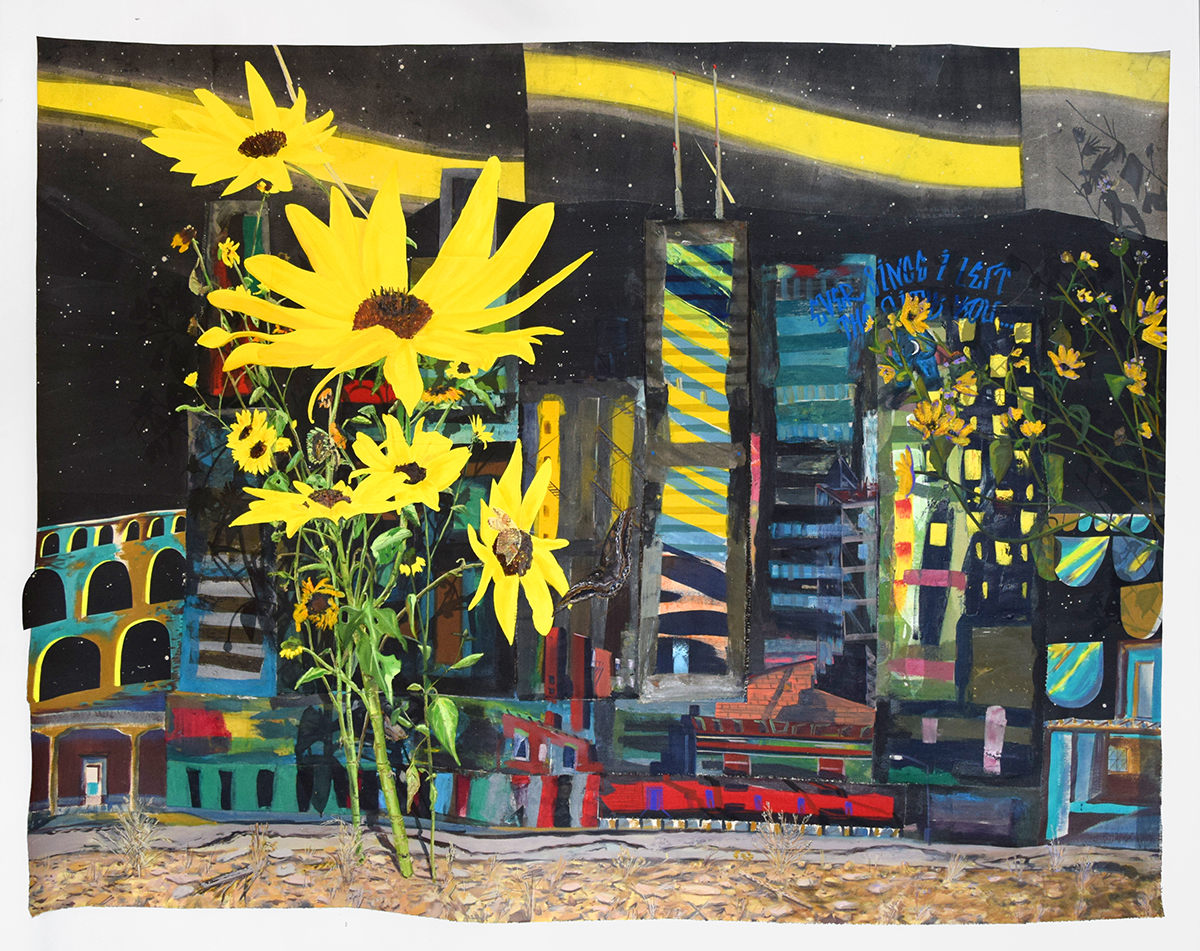

Paula Wilson, Sunflower Night, 2022, acrylic and oil on muslin and canvas (relief, woodblock, and monotype print), 68 × 89 inches. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

Paula Wilson, Sunflower Night, 2022, acrylic and oil on muslin and canvas (relief, woodblock, and monotype print), 68 × 89 inches. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

I first encountered Paula Wilson’s art as an MFA student in Gregory Amenoff’s office at Columbia University. I was drawn to an image that featured a female figure in a garden amid the kind of dappled sunlight found in the work of French painters such as Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Henri Matisse. There was a feminine buzz to this print, a harmony between the woman’s body and the grass and flowers rubbing against her naked backside as she painted. I loved seeing this active femme figure whose relationship to nature seemed so symbiotic. In 2012, when I encountered this work, sophisticated pictures of ecofeminist ideas were rare. This was even truer in 2006, the date the print was made. I could not wait to meet the woman who made it, but I found out that she did not live in, or often travel to, New York City. She lived in the nine-hundred-person town of Carrizozo, New Mexico. When I met Wilson at a party for the launch of Kara Walker’s A Subtlety in 2014, she invited me to come stay with her and her partner Mike Lagg at their mostly hand-built and painted home/studio/museum. In the following conversation we discuss how Wilson’s show Imago, currently on view at Denny Dimin Gallery, brings the life of that lovingly made place to New York City.

—Heidi Howard

Heidi Howard

An influential text for you has been Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” When I listened to a recording of Lorde read this text I felt a vibration, very similar to what happened when I saw your work for the first time. I see your show Imago as being about cultivating space in a way that is erotic. Can you talk about making a site for yourself and others that has this energy?

Paula Wilson

After I moved to Carrizozo I felt like I had the space to tap into and access my erotic energy. In the studio sometimes I feel a sensation in my groin chakra, or root chakra. Sometimes, when I’m making art or puzzling through ideas, I’ll feel my root chakra start to tingle. I have come to the conclusion that this is an indication that I am on the right path or that I should follow through on whatever idea triggered this sensation. Lorde talks about an “internal sense of satisfaction” that turning toward the erotic provides. When something “feels right to you,” Lorde encourages listening to this awareness. We have been robbed of this kind of erotic power in favor of the pornographic. Moving to Carrizozo and being with Mike and communing with nature allowed access to the erotic for me. I identify as an ecosexual, and the desert has brought me the felt wisdom that I try to reflect in my art. And as you said, making space for me and others is a component of Lorde’s erotic as well—this sharing. The Carrizozo Artists in Residence program and MoMAZoZo become part of that story as a way of building space in the desert for others to access their own depth and power of feeling.

Paula Wilson, Life Spiral, 2022, digital video, 5 minutes and 32 seconds. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

Paula Wilson, Life Spiral, 2022, digital video, 5 minutes and 32 seconds. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

HH

Thinking about the bodies in your show, the flying elements, and the human-made structures that are so connected to their surroundings, some of the themes that come up for me are “freedom,” “America,” and “western landscape.” Are you reacting to any of these terms in the work?

PW

Hmm. When you first said “freedom,” I associated it with freedom from fear, the freedom to move toward and into love, the freedom that being an artist generates in terms of breaking free of the confines and boundaries of society. If someone says the work is free or freeing, that is a great compliment to me. Then when you followed with “America” and “western landscape,” I tensed up. I feel very connected to my environment in the west where I have been for fifteen years. Yet I do not identify with many of the artists we call western artists, nor do I relate to the landscape painting traditions that continue a kind of Manifest Destiny relationship to the land. The video Life Spiral was shot exclusively by me and Mike in and around Carrizozo. It tells the story of the life cycle of a winged insect as embodied in human form—my form. It holds an otherworldly reality that feels true to our human life and sense of place. I also think of the salon-style hanging in the gallery that has traditional landscape pictures in the mix. For me there is a self-awareness in the pieces because of their faux frames and faux shadows. They are ironed on the wall so that their profile is flat. It is as if the pictures themselves are aware of their own existence. That self-awareness is what garners power for us to see ourselves seeing. There is no more powerful sense of place than to be in your body wherever you are standing.

HH

The painting Sunflower Night (2022) is caressed with light from a lamp made by Mike. I love how the sunflowers in this painting feel like a light attached to his lamp. They contrast with the cityscape. I see New York or Chicago skyscrapers and Roman arches, seemingly the concept of a global metropolis; at the same time, the ground at the very front of the painting is the ground in New Mexico, that very dry ground that somehow grows the tallest sunflowers in late summer. Can you talk about this painting? To me, it feels like an anchor in the show. I am also curious about your relationship with sunflowers, an ongoing motif in your work.

PW

I like the way you said that—caressed with light. Halfway through making this painting Mike made a streetlight-inspired lamp to pair with it. It changed the trajectory of the piece. I painted the flowers in response to the light. Their exuberant scale and orientation would have never manifested in this way without this outside light. It is as if the flowers grew toward the light. I spent pretty much my entire life in cities before moving to New Mexico. I still find myself turning much of my attention toward shows and people that I love in these urban centers. I think that is what this painting is kind of about: the fact that I could fully bloom in the light of the sun in the desert, but the backdrop of my being is urban. Sunflowers are in our garden and grow wild about town. They rotate toward the light. They demand to be seen, and I was happy to oblige their calling.

Paula Wilson, Earth Angel, 2022, acrylic and oil on muslin and canvas (relief, silkscreen, monotype, and lithography print), wooden and beaded jewelry made in collaboration with Mike Lagg, 155 × 155 inches. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

Paula Wilson, Earth Angel, 2022, acrylic and oil on muslin and canvas (relief, silkscreen, monotype, and lithography print), wooden and beaded jewelry made in collaboration with Mike Lagg, 155 × 155 inches. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

HH

You can see a thirteen-foot-high Earth Angel (2022) rising up through the window before you enter the gallery. She talks through her skirt to the adobe decal you added to the gallery’s facade. She also contains houses, moths, pomegranates, and the moon. Your monumental figures hold so much space and energy. I remember first seeing them at Smack Mellon. How did you conceive them? Are they related to totems?

PW

I made my first large figure in 2006. I didn’t set out to make her. It was a frustrating time in the studio for me after graduate school. I just kept cutting and cutting up my own paintings and prints in an attempt to get at something fundamental or elemental in the work. But I just ended up with a pile of scraps. One day I started gluing all these pieces on canvas and the figure started to take form. Another unrelated painting in the corner of my studio became the shoulder and head. It was as if the figure built itself. I don’t think of them as totems, but I do think that is a keen observation. I love how they hold so much information, but it is all contained within their form, not within a rectangle or picture plane. It feels like a more ancient form of storytelling and related traditions of ceremonial dress. I print and sew most of my own clothes, so it feels right that my paintings are also outfits, albeit at a monumental scale.

HH

You seem to use Facebook and Instagram naturally, interweaving these media as you do video, printmaking, and painting in your work. Can you talk about how you interact with technology and the importance of crossing boundaries of genre and medium?

PW

That’s nice to hear, although I don’t see myself that way in terms of garnering followers and being good at posting regularly. In graduate school I inserted video into my paintings. This was before tablets and smartphones made this inclusion easy. Holding these screens in our hands is a radical new platform for imagery. I’ve never been able to fit my work within a single genre or medium because that feels antithetical to the diverse and technologically abundant world we live in.

Installation view of Paula Wilson: Imago, 2022. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

Installation view of Paula Wilson: Imago, 2022. Courtesy of Denny Dimin Gallery and Paula Wilson.

HH

You have tablet holders in your living spaces, handcrafted in wood by Mike. He also utilizes his waste materials by turning much of them into sculptures and usable means. This ecological way of living makes me think about the future. Technology is a part of that future, as well as a potentially more thoughtful and accountable way of being human.

PW

Technologies of all sorts have been the driving force for artistic innovation. From paint being put in tubes to the development of the camera. Choosing artful ways to integrate and interface with these technologies is a task we welcome as artists.

Paula Wilson: Imago is on view at Denny Dimin Gallery in New York City until October 29.

Heidi Howard’s work stems from the practice of portraiture. They were born, raised, and currently live in Queens, New York.