Meet Multimedia Artist and Activist Sheida Soleimani – Picter Blog

AUGUST 6, 2023 Katharina Siegel

“What a Revolutionary Must Know”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“What a Revolutionary Must Know”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

Sheida Soleimani is an Iranian-American multimedia artist, activist, and professor. Her innovative works in ‘constructed’ tableau photography spark dialogues on the intersection of art and protest, particularly emphasizing ongoing human rights violations in Iran.

When and how did you first get involved with photography and arts? What initially sparked your interest?

My maman’s old canon with a dead battery sat in her suitcase (that she escaped the country with) for a long time. Maybe its presence looming over me made me decide to pick up a camera? Not exactly sure what sparked it, but I began by shooting film photos of flowers and abandoned factories in rural Ohio where I grew up. I saw photography as a way to find and create safe spaces in a place that was not hospitable to my family or any form of otherness. World building and adventuring became a way of escape.

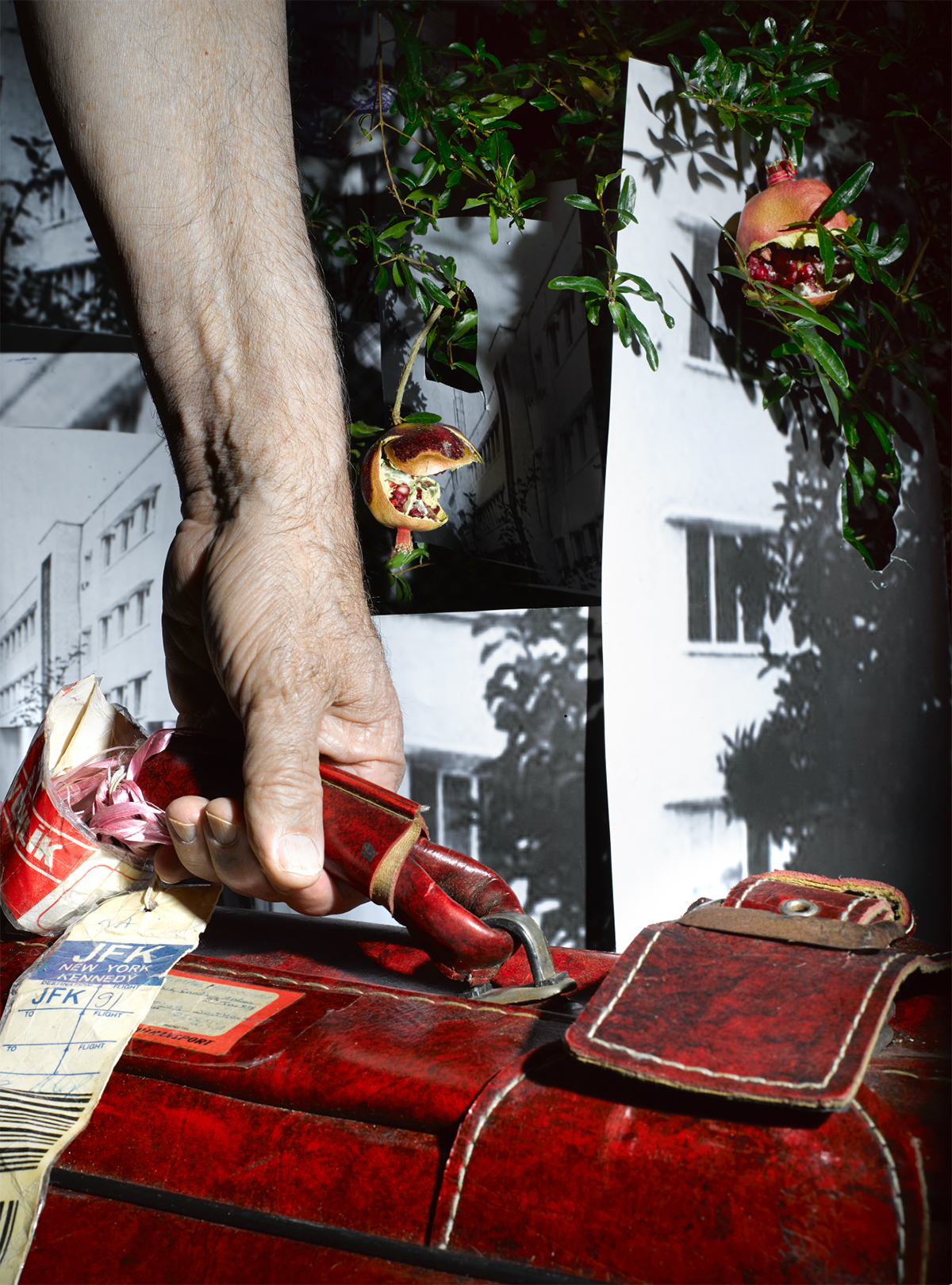

“Safar”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Safar”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

Can you tell us a bit about your project ‘Ghostwriter’?

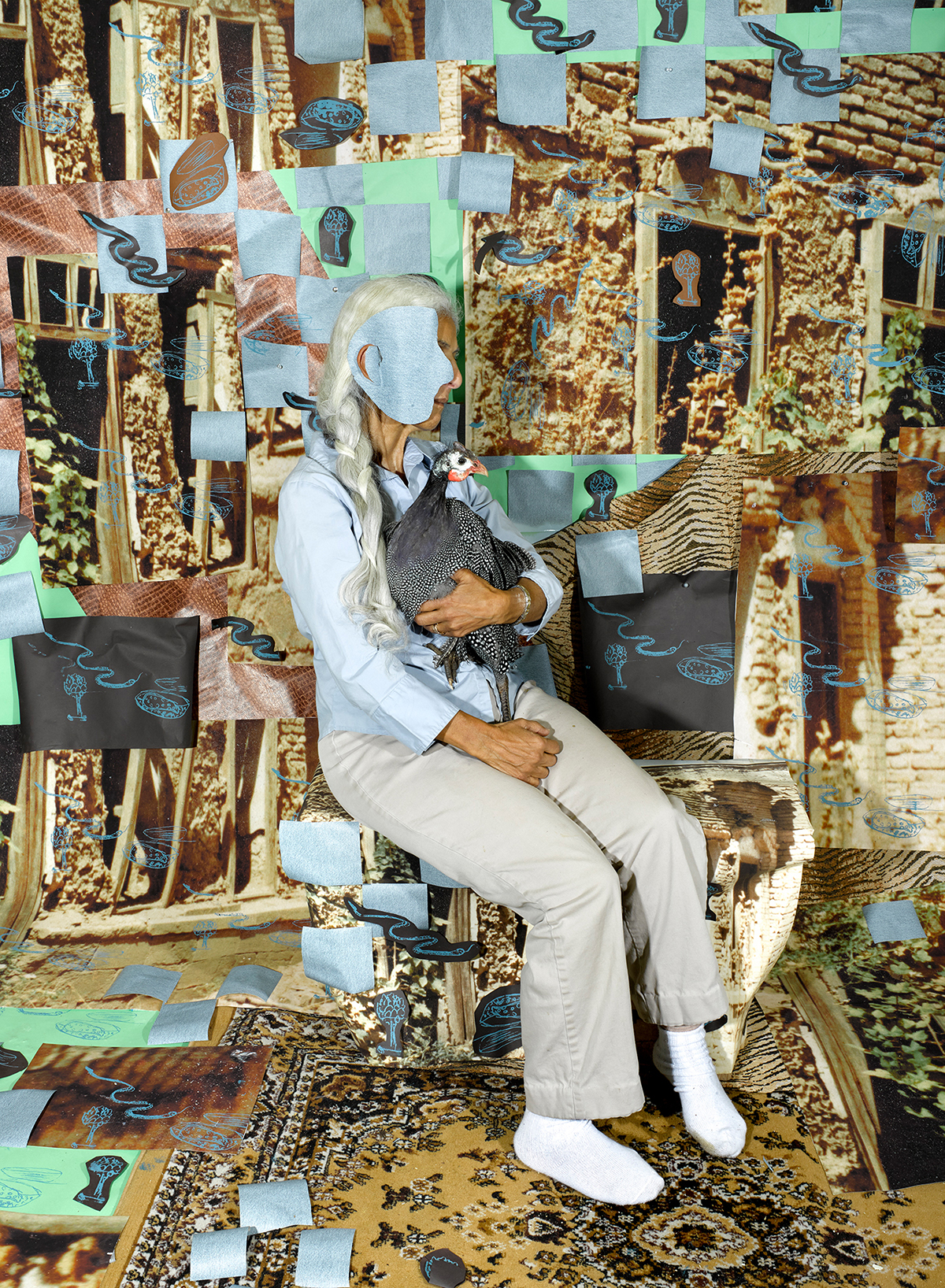

For the first time, I’ve decided to turn my camera inwards to explore my maman and baba’s history of exile from Iran, as well as the transference of the notion of home. The series of tableaux (constructed) photographs ‘ghostwrites’ my parents’ lives and stories, while tracing their time living in Iran as pro-democracy activists and the conditions that led to their displacement to the United States. Casting my parents as the protagonists, each photo symbolically recounts the memories surrounding my mother’s home and the unfolding of their urgent departure as Iran’s regime tightened its response to dissent.

“Noon o namak” (bread and salt), 2021 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Noon o namak” (bread and salt), 2021 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Khooroos (rooster) named Manoocher”, 2021 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Khooroos (rooster) named Manoocher”, 2021 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

How did it feel to present such an intimate project that also deals with parts of your family’s history to the general public?

I’ve held off on making this work for years, mostly because I find that the art world (and society at large) essentializes individual’s stories and is more obsessed with the pornography of pain than they are with the stories and the people actually involved in them. In fear of my parent’s narratives being used for click-bait worthy articles, or being reduced to abused individuals for audience consumption, I have waited until I felt like I would have the proper language and ability to control how the story is circulated and who it reaches. It still feels scary, because not only is this deeply ‘personal’ and vulnerable, but it also is where I have been wanting my work to go for the last few years, and that’s caused a lot of pressure. But it also feels really natural for me to be stepping into finally making this, as well as realizing ideas for photographs that I have had for over a decade.

Sheida Soleimani photographed by Eden Tai.

Sheida Soleimani photographed by Eden Tai.

Symbolism seems to be a significant aspect of your artwork. Would you mind discussing some of the key symbols and their significance to you?

Totalitarian terror compels people to develop strategies and practices for protecting themselves that people in democracies never need to know about and rarely consider. Like camouflage, blending in becomes a survival tactic; communication is fraught; and, generally speaking, individuals often assume they are under some form of surveillance. In Iran, this situation is hardly new; for more than four decades, Iranians inside and outside the country have developed complex ways of coding their language — both verbal and visual — to survive.

Oftentimes, the West criticizes Iranian artists for not being direct enough in their visual and verbal language, expressing difficulty in deciphering an inexplicit symbolic language. Many Iranians have seen and felt the consequences of being direct, and not many are willing to risk their lives. However, even with the use of symbolism, there are still consequences to pay. Iranian artists are still forced to use symbols as indirect expressions of their ideologies. Artists of the Iranian diaspora often use symbolic coding in a similar way, though often far more directly. For members of the diaspora like myself, there is no imminent threat of imprisonment or death, but speaking out against the regime in any way can result in the threat of exile. Within the diaspora, this threat has become a divide and raises a question for immigrants, as well as first and second-generational individuals: how explicit should you be about your politics, and what repercussions can your opinions and art have? One example of a symbol repeatedly used in my work is sugar- and in many different forms (raw sugar, icing, cubes, etc). The reference point for this specific repeated symbol nods to the slaughter of lambs in Iran: a sugar cube is placed in their mouths to pacify them before their throats are slit- an analogy for the failed revolutions in the country and the government’s way of handling dissenting individuals.

“Behind the Door”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Behind the Door”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

What are your thoughts on the contribution of photography towards political activism and exposing human rights abuses?

So much of the art world is filled with ‘activist art’ that is self-serving, or even worse, images that have no content. I feel like it’s the job of artists to put images into circulation that tackle critical events and bring information to light about overlooked topics.

“Field Hospital”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Field Hospital”, 2022 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Khoy”, 2021 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Khoy”, 2021 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

As a photography professor, what advice or tips would you like to offer emerging artists, especially those working with themes such as politics, human rights violations, and identity?

Take risks, ask lots of questions, and DO YOUR RESEARCH!!

Are there any other art forms you would like to explore in the future?

For an upcoming museum exhibition, I’ve decided to create a full-sized sculpture of a horse- made out of foam, and hand screen printed fabric. I’ve never taken on anything like this before, and it’s been quite the learning curve!

“Remorse”, 2023 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.

“Remorse”, 2023 – Courtesy of Denny Gallery and Sheida Soleimani.