STRAIGHT TALK with Dana Sherwood

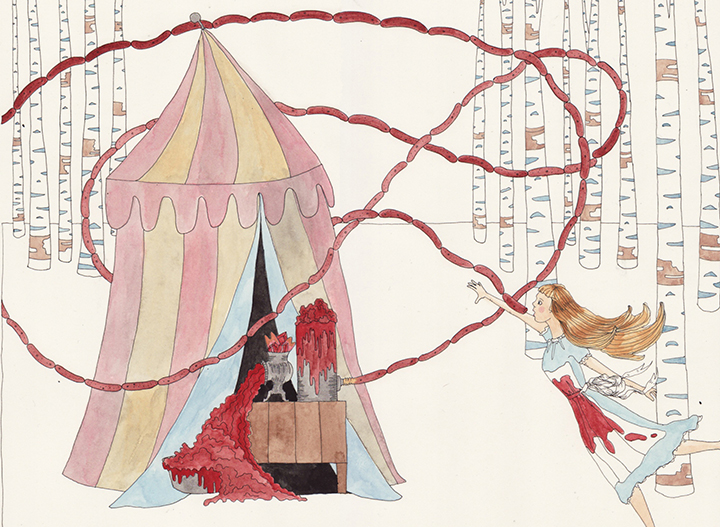

Dana Sherwood is a New York–based artist who blurs the line between the domestic and the wild through her mixed media and documentary art. Concerned with “the semiotics of desire and melancholia present at the intersection of the two worlds,” Sherwood’s work explores novel ideas such as what it means, and what it looks like, to create a picnic basket for South African baboons. Sherwood has exhibited internationally including at New York’s Marianne Boesky Gallery, Mixed Greens Gallery, Socrates Sculpture Park, and Flux Factory as well as in Toronto and throughout Europe.

By Danielle Kalamaras, Contributor & Blog Editor

DK: Your work crosses many media including drawing, video, and installation. How does mixed media production motivate your multi–disciplinary practice?

DS: For many artists I think the work is often driven by the idea more than by the media. Of course, the physical expression of the work must be paramount, and there is a delicate line to walk to ensure complete symbiosis of these two very important aspects. In my practice I spend a long period of time doing fieldwork, such as scoping out film sites, preparing food, and setting out cameras, and my studio practice complements the kinds of things I am doing in the field. It gives me space to think through ideas and push myself to open the scope of interpretation. I spend most of my studio time making the watercolors based on the fieldwork, writing, and finally producing the finished work. It’s a long process with many complementary elements.

DK: Your piece Crossing the Wild Line will be exhibited at the Denny Gallery in NYC early next year. The work itself is a food cart containing such items as cookware, cookbooks, bowls of fruit, and meat. The piece was originally located in the Botanical Garden of Brasília. Videos documented the natural world’s interaction with the living sculpture, and the cart along with these videos were later moved into the gallery spaces of the Cultural Banco do Brazil, Brasília for the exhibition “Cru.” How does this journey between spaces add new dimensions to your work?

DS: By having the work evolve in the two locations it emphasizes the idea of the domestic versus the wilderness. Brasília is a really interesting city. It was built in 1960 in the center of the country, which was at that point a vast wilderness hundreds of miles from civilization. Oscar Niemeyer, who planned the city, intentionally left large swaths of it undeveloped and left as savannah. Part one of the piece happens outdoors, and is only seen by an audience of animals. During part two, people are able to experience it inside the gallery. The video monitor mounted onto the finished sculpture provides a kind of surveillance view of what happened in the forest and how the animals interacted with it.

DK: You were recently featured in “Humanimalands” at SVA’s CP Projects Space. The works on view abandon the separation between humanity and nature and instead embrace an intimate integration of the two, and include a meditation on the ‘anthropocene’—the term coined by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer to denote the present time in which nature is significantly altered by human activities. How does straddling such tropes like ‘man versus nature’ influence your work? How did this concept directly impact your work for this exhibition, and your work in general?

DS: I don’t think of my work as ‘man versus nature’ as much as I think about exposing the fact that nature exists everywhere, right under our noses, even though it is easy to forget for those of us living in the concrete jungle. While I love the idea of going into pristine nature and experiencing wildlife in its ideal environment, I am more interested in examining how nature has evolved in the anthropocene—which means looking at disturbed territory and uncovering how nature flourishes in those places.

Raccoons are my favorite subjects because they have really figured out how to thrive in the new ecosystems. We now find that populations of raccoons positively correspond with the populations of humans in an area, by observing raccoon’s adaptation of behavior and diet. Strangely enough, Toronto is the raccoon capital of the world. For the work featured in “Humanimalands” I spent three months deep in the suburbs of South Florida where my backyard extended into a sort of sub–tropical no man’s land along an extensive canal system. Several nights a week I would set out a table filled with elaborately constructed platters of food and set up one or two ‘camera traps’ of the sort used by hunters to track game in the forest. The camera traps are ideal because they are heat-sensor activated, are weatherproof, have night vision and are designed without sounds or lights that would scare off any animals. They have the visual quality of surveillance cameras, kind of grainy and flickering, and are also reminiscent of early cinema. This gives them a nice aesthetic sensibility while underscoring the idea of being watched. I regularly get a cast of raccoons, opossums, foxes, and if there are leftovers in the morning, vultures. Planning is hard for this work so I tend to think of it as collaborative. Over the years I have learned that the only certainty is uncertainty. Wittgenstein wrote, “if a lion could talk we could not understand him,” perhaps implying that we do not have the ability to comprehend the alternate universe that exists in the mind of a nonhuman animal.

Keeping this in mind, I try to remain aware of my anthropomorphic assumptions, but I think these experiences have made me realize that our language is indeed very different, and it is worth engaging and learning to embrace the chaos of plans gone awry. The work shown in “Humanimalands” is really a best case scenario. Raccoons are fairly habituated to humans and do not have such a strong flight instinct as deer or other shy animals. It is also advantageous to have a long period of time. Often animals are afraid of anything new in their environment and it can take weeks for them to become bold enough to approach even something as benign as a carrot.

DK: Your work is heavily influenced by biology, but also often incorporates food. This dichotomy between living organisms and cooked food really symbolizes one way humanity frequently modifies nature’s ecology. How does this cycle (from living thing to human nourishment) motivate your creative process?

DS: Claude Lévi-Strauss observed, “cooking food is a metaphor for the human transformation of nature into culture.” Cooking is the thing that separates us from other animals, but it can also be the thing that brings us together. Cooking and its relationship to domestication and the taming of the wild initiates our long history of manipulating the natural world to suit our desires. The theme of the manipulation of nature is a big one for me and I think food is a perfect metaphor for this idea, especially the sculptural displays of food from the 19th century though the 1960s that I usually model my presentations after. They become so architectural and non–food–like, it’s a wonder anyone ever ate them. Also, serving food is the best way to make friends. We use feasts to celebrate significant events and also to enjoy the company of loved ones. In the wild kingdom it serves as the easiest way to attract animals to places where they can be observed without forcing them into confinement. In a way, they remain there on their own terms and it makes it possible for me to film animals just being animals.

DK: How do you feel integrating science into art (and vice versa) will help stimulate innovation within the two disciplines?

DS: Being an artist, I have a lot more freedom to experiment without adhering to the scientific method, and I allow my curiosity to take the lead. What I do is very unscientific; however, I think the issues I’m looking at are timely and complex. I would love to think that my works fuels a discussion that could help bring about creative ways of problem solving. We are in the midst of an epoch where the destruction of animal habitats and exploded development has forced us to live in close proximity with other species. Every week I read in the paper of bear sightings in Florida, raccoon evictions in Brooklyn, baboons in Cape Town, and leopards in Mumbai. Nobody wants to hurt these animals, but we have yet to come up with an effective way to live together.

DK: You frequently collaborate with your husband, Mark Dion. How does working with another artist shape your process? What are a few recent collaborations you two worked on together?

DS: While Mark and I make different kinds of work, there is a strong overlap in the poetics of environmental concern and we both spend a good deal of time in the field, sometimes working with scientists and naturalists. We are very easy collaborators, and when we work together we are able to feed off each other’s ideas in a very productive way. This is a rare gift. We are really due for another collaboration soon. The last project we did together was in 2012, called Encrustations, and was part of an exhibition called “International Orange,” celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Golden Gate Bridge. The show was at Fort Point, a Civil War era fort situated directly below the bridge. It is a place of extreme weather, prone to flooding by the turbulent sea at its doorstep. In fact, the only battle that ever happened there was between the fort and the sea. The work imagines the structure had been engulfed and submerged by the Pacific Ocean, and the various personal and military objects left behind were both destroyed and transformed by the ocean, releasing them into a new life and life forms. The objects, housed in two wood and glass vitrines, are no longer recognizable as shoes, hats, cannonballs or spoons, but hybrids of culture and nature, colonized by ocean organisms such as barnacles, algae, mollusks and sponges of all variety.