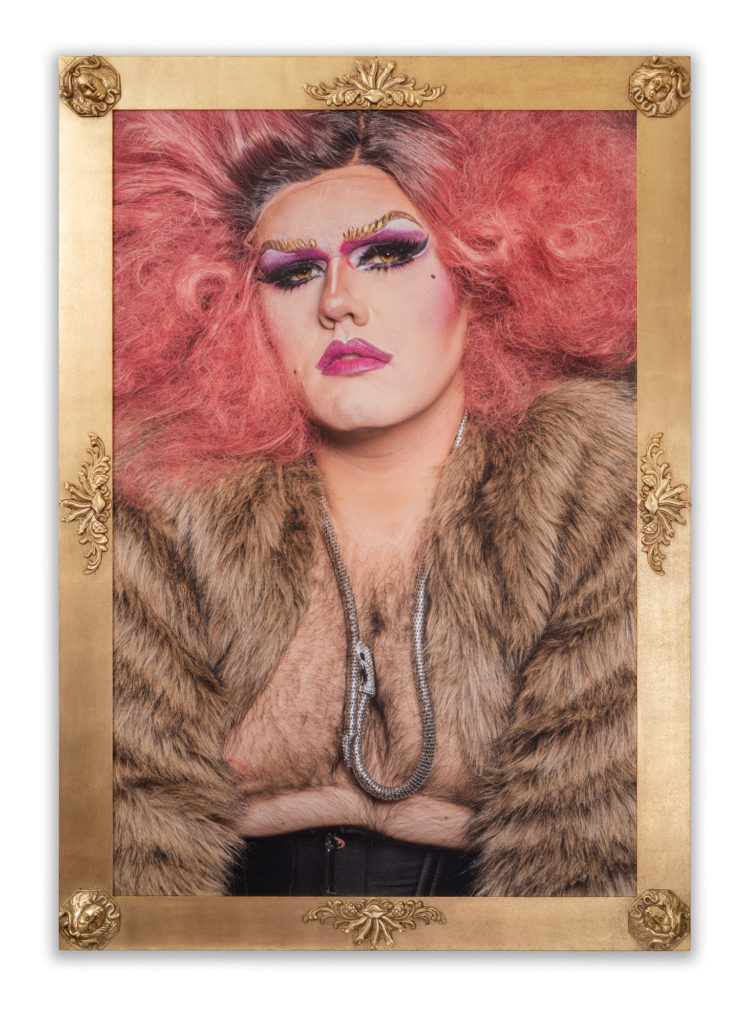

@Beefcake_Dragqueen #queer #instagay #instabear, 2020 © Sean Fader

The Digital Limits of Queer Trauma and Celebration

Sean Fader uses two photographic series to bookend a transformative two decades of LGBTQIA history through the lens of digital photography and its role in queer representation.

A lot has changed since the first mass-market digital camera was released. Not just in the quality or accessibility of digital images, but how we think about image culture. How we think about selfies. How images are tracked and geotagged.How photography builds connections and relationships. How we use it as a historical record. How we celebrate ourselves, and how we memorialize pain.

Sean Fader’s latest exhibition Thirst/Trap, on view (from a safe and social distance) at NYC’s Denny Dimin Gallery, pairs two recent series to address how technology, accessibility, and self-reflection have shaped queer communities and identities. They do this in strikingly different ways – one from a place of celebration, and the other from a place of terror and mourning.

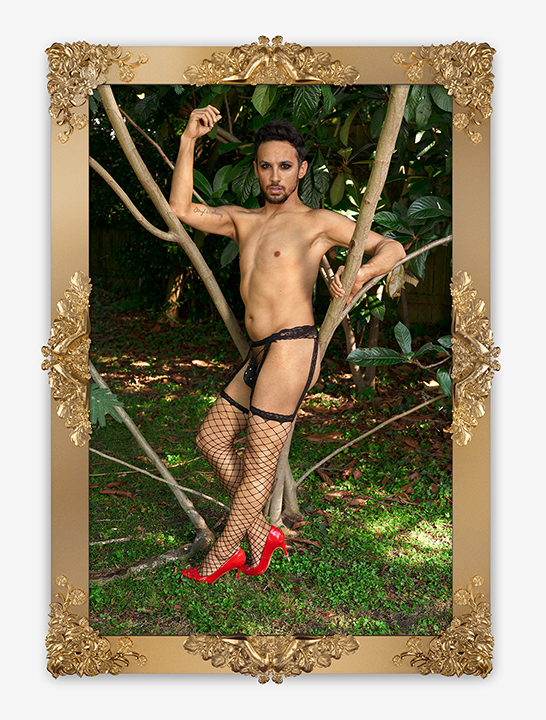

Best Lives is a series of collaborative portraits Fader made with sitters he met online using hashtags like #instagay, #nonbinary, and #genderfluid – proud references to self-identity and community forging. Fader then photographed his sitters, asking them how they wanted to be represented. The bold and colorful images – often with gestural nods to early painting – capture ostentation and self-determination.

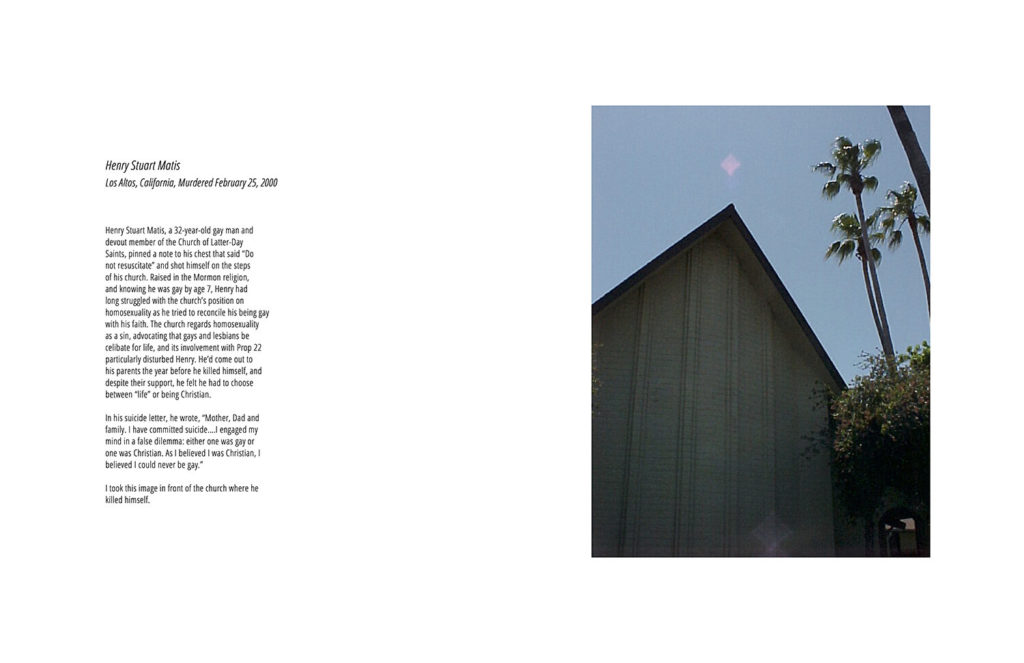

In stark contrast, Insufficient Memory reflects the pain and trauma associated with over 50 reported anti-LGBTQ hate crimes committed in the United States in 1999 and 2000. Fader drove thousands of miles around the country photographing the sites of these murders, locations that are largely unmarked. Fader used a Sony Digital Mavica camera, which was released around the time these murders took place. The camera’s low resolution creates pixelated and blurred images that reflect the anonymity of these locations, which Fader pairs with text describing the horrific hate crimes.

Contrasting two periods of time significant to the rise of digital photography and its impact on mass culture, Thirst/Trap highlights how identity and representation have evolved, how they are celebrated and memorialized, and the limits images have to record or reflect history.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Sean Fader

(content warning: the text accompanying the images for Insufficient Memory describes awful, violent traumatic hate crimes.)

Jon Feinstein: Did you originally imagine exhibiting these two distinct series together?

Sean Fader: Oh my god, no. I never thought they would be in the same show. I guess I was making both at the same time because I needed the emotional balance that was happening in the two of them. One felt so celebratory, and the other one felt so dark. When I was making Insufficient Memory, it felt really, really hard every day, and one of the ways that I was able to pull myself out of those dark places was to make the optimistic celebratory work in Best Lives. I think because I was making them concurrently, the ideas that were coming up in both bodies of work started to play off each other.

Feinstein: To your point, these two series have opposing yet complementary qualities. One is steeped in pain, violence, and bigotry, the other is bright, bold, celebratory.

Fader: When I am in making mode, it’s rare that I have any real perspective on the work. I’m so deep in it, digging down and excavating, that I often forget to look up and see the sky. In the beginning, I don’t think I even realized that I was dealing with queerness, visibility, photography, and Internet technology like bookends of an era 20 years apart, but the works were definitely influencing each other and having a conversation. I didn’t really realize how much that had happened until we talked about putting them in the same show.

Feinstein: I interpret your use of gilded frames for Best Lives as a celebration, commentary on, and embrace of outward confidence of online performance—a kind of reclaiming of self-representation, a positive embellishment, a middle finger to those who deserve it, a kind of wonderfully blatant: “We’re here.”

Fader: Ha ha. I guess I wasn’t really thinking about them as a middle finger, but I love that idea. I did want them to be extremely celebratory and to celebrate queerness unapologetically. On this large of a scale that probably feels like a middle finger to a lot of people. My focus was trying to reinsert these images into an art historical context.

I grew up going to the Met and seeing the celebrated society portraits in giant gold frames. The frames felt like they were telling me that these people and these paintings were important. I wanted to trigger that same response. I wanted to make you feel like the thirst traps and selfies of queer people are the society portraits of today, and I wanted to celebrate and honor these people.

Feinstein: I have only experienced these portraits digitally so far. I imagine they feel even more regally confident in person?

Fader: One of the things that I realized when we installed Best Lives in the gallery was that the pieces are so large that they feel like bodies in the room. They also feel ethereal and as if they could float away. The backroom is completely the opposite, it’s empty of physical objects. It’s only inhabited by projections that feel like the ghosts of queer people that were lost to violence. The backroom becomes a sobering anchor that nails the large portraits to the ground.

Feinstein: Insufficient Memory functions on a few levels for me:

a) the pixilation as it relates to the confusion and erasure of memory and history – the pain we might want to forget, but of course, not forget…

b) your use of technology of the time to reference and memorialize the victims of horrible violence that occurred during this time.

Can you talk a bit about your initial conceptualization?

Fader: The work was initially conceptualized when I moved into my office at Tulane, which I inherited from a photo hoarder (you know the type). When I was digging through all the cameras, expired chemicals, and junk from still lives past, I found this camera, the Sony Digital Mavica. I looked at it and immediately had a flashback to meeting my ex’s mother for the first time. She lived in the Deep South, was an Internet junkie, and wanted to be a PFLAG mom. I started thinking about that moment in time and my experience of being a gay man then (now I think about myself as a queer person). As I looked at that camera, I thought a lot about visibility, queerness, and technology back then.

So, I started doing research, both about the camera and the queer histories at the time the camera came out. The Sony Digital Mavica was the first commercially successful digital camera in 1999 and 2000 because it shot to 3.5-inch floppy. In 1998 Matthew Shepard was murdered, and in 1999 President Clinton told Congress in his State of the Union that he wanted to update the federal hate crimes bill to include LGBT people. He promised to sign it. While the 106th Congress debated whether LGBT people should become a protected class, people were dying.

In my research I came across a spreadsheet of hate crimes against queer people, and since it was a spreadsheet, I could organize it by year. I zoomed into 1999 and 2000 expecting that I would know many of the names and realized that I didn’t know a single one. In that moment I felt a cross between ashamed and angry. I began researching them, and I realized that I didn’t know these stories because most of them didn’t get that much coverage. For many of them, I couldn’t find more than one sentence. I then spent the following year and a half working to find as much information as I could on each of their stories so that I could tell them.

A screenshot of the Google Earth map for the location of the hate crime against Henry Stuart Matis

Feinstein: How did this develop and translate into a photographic series?

Fader: As I researched, I started putting all these crimes on a Google map. I kept looking at the map and thinking I need to go to all of these places. From a technical standpoint, I knew that I needed to photograph them using the Sony Digital Mavica. I knew it was important for me to use the technology of the time to talk about how queer erasure happens; not just from people ignoring the stories the first time around but also because of how the digitization process happens.

Many of the queer newspapers of that era are impossible to find because they were never archived and never scanned. The images produced by the Sony Digital Mavica are 600×800 pixels (about 1/3 of a megapixel). When I printed those images very large the images became both ghostly and violent. The images revealed something about a reality but also concealed so much because the resolution is so bad. For most of the victims, the press did the same. I struggled a lot when I was making the images because I didn’t know how to use the camera. It’s sort of cruel and unforgiving because the light needs to be just right to get a decent exposure. I will say that I never expected to like the photographs, but I love them.

A screenshot of the Google Earth map with pinpoints to the hate crime locations Sean Fader photographed

Feinstein: As you began making these images: sat, stood and photographed in these locations among the pain and ghosts, did new revelations come about, moments of clarity, reflection, etc.?

Fader: I think the process of physically going to these places was one of the hardest experiences I’ve ever had in terms of making a photograph. I thought the hard part was going to be driving 15,000 miles to 38 states. I was wrong. When I stood in those locations, I had such a sense of grief and loss mixed with fear for my own safety. I didn’t realize the emotional impact me I would feel every single time. I cried a lot the past year.

Feinstein: As a viewer, it’s incredibly hard to process – I can’t even imagine. Both of these series seem to build on your larger practice, which addresses self-portraiture, queer identity, technology, and, in stark contrast to the pain of Insufficient Memory, often self-referencing humor. I recall being struck by your 2008 series I Want to Put You On….

Fader: My undergraduate degree is in musical theater, but I grew up with a darkroom in my basement because my mother was a photographer. In the end, if I were to distill my practice down to one epic idea it would be that I am always thinking about the photographic event as the site of performance and how we create, disseminate, and digest those images in digital public spaces (like Instagram) so that we can understand ourselves, our place in the world, and others. I know it’s a mouthful. I think that in varying degrees these themes show up in all of my work. In some work, the focus isn’t as direct, but there are always a bit of underlying questions around those ideas.

@Danny_girl_official, #boylesque #genderfluid #nonbinary #IAmArt #MenInHeels, 2020 © Sean Fader

Feinstein: How has the process of making this work and getting it to the point of exhibition helped you understand things about yourself/your own experience, identity, etc.?

Fader: Well, I’m not sure that is exactly what I meant though I guess that is probably true. Part of me wants to say that that understanding just comes with age. I also think that making work about how we all understand ourselves and others through the performances of self in digital public spaces might give me a bit of a leg up understanding myself. When I was younger, I was angry that people always talked about me as an emerging gay artist. I wanted to just be thought of as a great artist. I’ve moved beyond that. I want to be thought of as a great queer artist.

If I was given the opportunity to be reborn and to choose being straight or queer, I would choose queer. When I was coming up in the art world, I had several gallerists come to my studio and tell me that my work was “amazing, but really gay.” This was a blatant way of saying that they would never represent me because no one would buy work that could be seen as legibly gay. It just pissed me off. I kept making my work anyway, no matter what homophobic misogyny was thrown at me. I wasn’t gonna bury my queerness to make collectors comfortable. A few years back, a friend looked at me and said, “You’re so lucky—it’s really in to be queer.” I just laughed. I still don’t feel cool, but I feel great with myself and my work.

Feinstein: What do you hope viewers come away with after seeing and experiencing this work?

Fader: Oh, this is a complicated question because of the structure of the show and I’m too involved to have any perspective. With each body of work there are different questions I want people to struggle with. In terms of the two bodies of work that make up THIRST/TRAP, I want people to challenge the idea that progress is a one-way street. I want people to realize that queer people have not been in charge of their own narrative and that it’s important to change that power dynamic. I want people to find beauty and sadness in these stories but realize that they are important to tell. All told I want people to think about how important it is to fight every day for equality and humanity for everyone. Oh, and vote every single time.

Visit the Humble Arts Foundation website.