Art Mamas: Amir H. Fallah Paints a Roadmap for His Son

Katy Donoghue

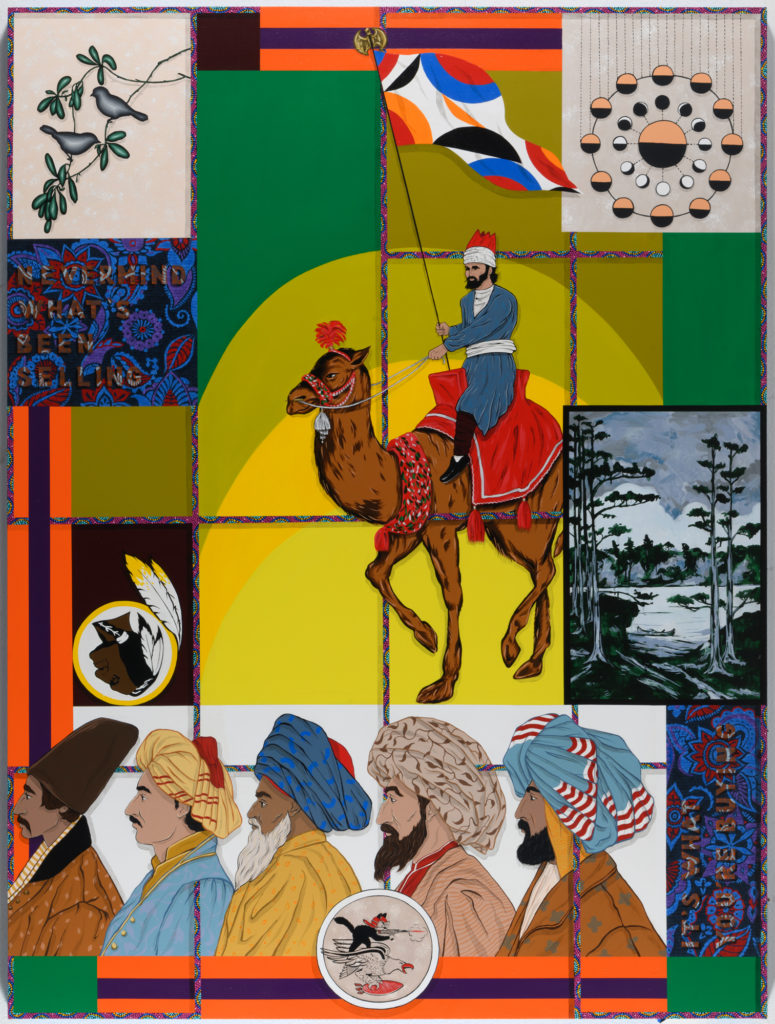

Amir H. Fallah’s show, “Better a Cruel Truth Than a Comfortable Delusion,” is currently on view at Denny Dimin Gallery in New York. The new paintings imagined as a how-to manual for Fallah’s son, featuring icons, imagery, and references to the culture that forms us—from advertising and pop culture to the books we read as children. Each work started from a text, whether a lyric from a song or line from poetry or film. In them, Fallah addresses issues like racism, xenophobia, climate change, immigration, and political division.

The Los Angeles-based artist is known for his vibrant portraits in which his subjects are obscured, visually revealed by the objects with which they surround themselves. This new series posits that what we consume, from even the earliest age, shapes our values and the way we see and interact with the world.

Given that these paintings are the result of Fallah thinking about how best to raise his young son, we asked the artist to be part of our ongoing “Art Mamas” series. Fallah shared with us why having a child made him unafraid of making art about social issues, inspiring him to take a stand about something.

WHITEWALL: What was the starting point for “Better a Cruel Truth Than a Comfortable Delusion”?

AMIR H. FALLAH: A few years back, I noticed that all the children’s books that we were reading to my young son were tools to teach basic life lessons like empathy, caring, compassion, equality. Before I had a kid, I thought children’s books were merely entertainment. I started photographing the illustrations in the books and thinking about this idea of instilling values into your kids at young age and how that has a ripple effect on the rest of their life.

What would happen if my wife and I disappeared one day before we had a chance to finish our duties as parents? How would our young son navigate the world and who would pass on our beliefs and values onto him? These questions were the starting point of the work. I began to make a list of various beliefs, metaphors, parables, and warnings that I thought were important to pass on to my kid. These short pieces of texts would be the starting point of each painting.

WW: When we previously spoke in the spring of 2020, we discussed revisiting children’s books we grew up reading with now our own young children, seeing them anew. Personally, I’ve had to reconsider classics like Curious George, where the monkey is not only stolen from the jungle but put in jail. You use that very image in Absolute Power Corrupts. But my son also loves this book. How are you talking about this kind of imagery with your son?

AHF: I had to stop reading that book to my son soon after I first read it to him. I never thought much about Curious George, but after reading it as a parent I realized so many references to colonialism and racism in the book. I became curious if anyone else had noticed the same thing and sure enough there are entire websites dedicated to this subject and many college thesis papers written on the subject. I had to take it out of circulation in our house. It felt like I was poisoning my kid with these images. I know we can’t protect our kids from the cruelty of the world, but I certainly don’t want to bring it into the most special moments with him.

WW: Are there any “new classics” you’ve brought into the fold for your son?

AHF: We have a lot of books dealing with equality, the importance of voting, and teaching empathy. It’s our job to shape and mold a compassionate and decent human into the population so we gravitate towards books that reinforce that. Most modern titles do a great job. It’s the “classics” that haven’t aged well.

WW: While this series is a how-to manual for your son, it offers adult viewers to reflect on the shaping of their own values. How has this made you reflect on what children’s stories impacted your world view?

AHF: My son was the catalyst for the work but that’s not necessarily important to the viewer. I’d like to think the work appeals to a wide larger audience. At its core it deals with the politics and social issues of our time like war, borders, politics, ethics. These are all themes that are accessible to anyone that is living in this complex moment in history. One other thing that I realized making the work is that, in a way, the work functions as self-portraiture. It’s capturing my place in the world and how I am trying to navigate life when we are being hit with disaster after disaster. In that sense I’d like to think that it’s a record of life in America in 2020.

For instance, the largest painting in the show Better A Cruel Truth Than A Comfortable Delusion directly speaks to our political situation. So many people denied the hate and rage that Donald Trump promoted and then two weeks before he left the White House, we had an attempted coup. The cruel truth is that this man should have never been elected and Republicans should have controlled him many years ago. Even after domestic terrorists tried to take them as hostages most of the Republicans wouldn’t stand up to Trump. If that isn’t a comfortable delusion, then I don’t know what is.

WW: When did you become a father?

AHF: 2015.

WW: Were you able to take parental leave? If so, what was the transition back like for you?

AHF: I work for myself so that is a hard question to answer. Did I make less work? Yes. Did I completely stop? No. For the first two years I stayed up and fed my son every single night. My wife had to go back to work after three months so I would stay up at night and paint in the garage with the baby monitor. Every couple of hours I would run in and feed the baby and then run back to the studio. It was a grueling schedule that has destroyed restful sleep for me forever. I don’t think parents can completely transition back to their old life. Your life completely changes after you have a kid. Nothing is the same. Some things are worse, and many things are better. It’s a rebirth in many ways for the parents.

WW: What has surprised you most so far about being a parent?

AHF: All of it. It is hands down the most challenging thing anyone will ever do. It completely changes you as a human. Also, I didn’t know you could love another person like that. You hear people say that all the time and you think it’s a cliché but then you become a parent and it hits you. It’s magical.

WW: How did it change who you found yourself connecting with?

AHF: Well, it’s hard to have the same connection with folks that don’t have kids. You have to work extra hard to keep relationships going with kid-less friends. It helps you weed out the excess in life. Also, dad friends are a real thing. I have a lot of friends now that I have nothing in common with other than that we’re both dads.

WW: Did becoming a parent change how you viewed your role as an artist?

AHF: Absolutely. For a long time, I had shied away from making work that dealt with social issues. But after having a kid I realized that I wanted my work to stand for something, to add a voice that might not have been there before, and to leave behind work that talked about the issues of the day. I’m not sure if art can change political policy or erase hate but art can bear witness to the times and be a record of the time that we’re living in.

WW: How do you experience art with your child?

AHF: Our kid doesn’t care for art that much. Somehow, he has become obsessed with the human body and anatomy despite having to creative parents. He walks around telling people he wants to be a surgeon. He is fiercely passionate about science, facts, and how the human body works. At first, I wished he loved art more but seeing him so passionate about a subject reminds me of my own love for art. Maybe he will become a scientific illustrator? As long as he is passionate about something, I’m happy. Some people go throughout life without anything to be passionate about. He discovered his passion at the age of three and has been going strong ever since. I hope it lasts.

WW: Historically, addressing parenthood or children in one’s work has been called “sentimental,” etc. Have you had this experience and do you see that taboo changing?

AHF: I don’t waste time thinking about things like that. You have to make art that you believe in and I believe 100% in what I’m making. When I was younger, I would overthink my work but now I am so excited to get in the studio every day and make work that I don’t care about what you can and can’t do.

WW: What is something another parent has shared with you that’s really resonated?

AHF: “Parenthood is all joy and no fun.” I think about that quote all the time.

WW: What is the biggest misconception about being a father?

AHF: That you’re off at some bar partying with friends while your wife raises your kid. I know this is true for some people, especially in our parents’ generation, but I’m involved in every aspect of our son’s life. My wife and I view our marriage as a partnership and we go into every situation with that mindset.