Installation view, “Wendy White: Pix Vää” at Leo Koenig, Inc. (all images courtesy Leo Koenig, Inc.)

What do you call Wendy White’s most recent works, which are made of two or more panels that rest on the floor, hug the wall and at the same time protrude from it? Combines and hybrids are the obvious answers, but those familiar designations hardly tell the story. There is something fresh about White’s work that these familiar designations don’t account for.

The panels are different thicknesses and sizes, and can be stacked or layered. One panel is an inkjet or digital print on stretched vinyl, the kind used in awnings. (White takes the digital images with her phone camera.) The other panel is acrylic on canvas. (These feature letters, words, and untranslatable acronyms in scripts that range from the cursive to the straight and hard-edged). In “11 Oliver” (2012), the third, cutout panel — which is also the smallest element — seems like an ideogram made up of right angles. The result: three different self-contained sections, each embodying one or more languages.

Wendy White, “11 Oliver” (2012), acrylic on canvas PVC and vinyl over metal frame, 73 x 120 x 4 inches

White’s seamless synthesis of unity and separateness distinguishes her work from the approach defined by Raphael Rubinstein in his article, “Provisional Painting” (May, Art in America, 2009), which included her as one of its practitioners. In fact, her recent works don’t seem provisional at all. In them — and more so than before — the formal aspects echo the subject matter. There languages of her means (photographic image, layered fields of paint, and cut-out shapes) reverberate with the languages of her subject matter (photographic image, abstract fields, and letters and words) with an unsettled cohesiveness — sort of like watching a dance in which the configurations and partners keep changing.

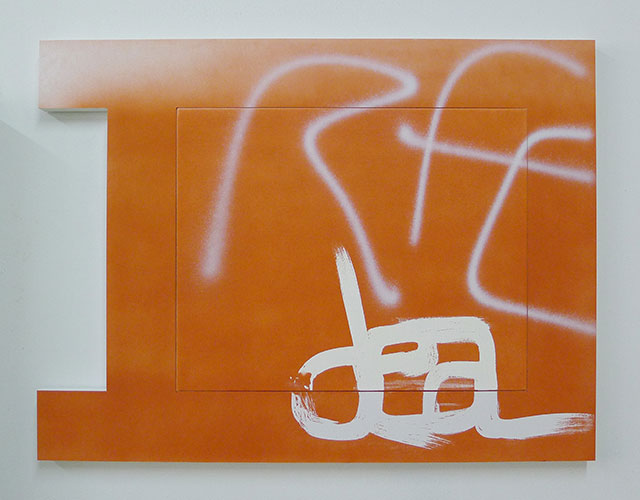

White orchestrates the differences without denying their identity. In “7 Monroe,” she juxtaposes two types of graffiti — spray painted (uppercase “RFE”) and brushed on (lowercase “dea”) — over an orange ground. Neither subdues the other. Are they acronyms, a secret code, or a tagger’s initials? That they remain indecipherable is part of the meaning of White’s work — her awareness of the various tactics adopted by those who resist absorption into mainstream culture.

Wendy White, “7 Monroe” (2012), acrylic on canvas, PVC, 26 x 28 x 1 inches

We have long recognized that language is not a transparent medium of thought, as Ludwig Wittgenstein observed, and Mel Bochner cited. However, by acknowledging that language has become a decaying residue, part of the accumulating layers and ever-present rubble of urban life, White goes one step further than Bochner, entering into an unstable and disquieting territory, which suggests that life itself has become provisional.

In “El Rocko Lounge,” the washed-out photographic image on the top panel seems to be fading right before our eyes. The viewer glimpses the rotated image of a building with a corrugated front. The top edge of the building, now vertical, is aligned with the leftmost edge of a scribbled-over letter below, on the lower panel. To the left of the unreadable letter, and visually more prominent, are the letters MLK.

In today’s society, everything undergoes degradation. Nothing is preserved, except as dregs and detritus. MLK becomes a sign, but of what — memory, martyrdom, resistance or grist for popular culture’s production machines?

By making each component distinct — visually, materially, and in its physical scale — White endows everything with a specific identity. By having the smallest component resting on the floor, with something larger stacked on top of it, she ensures that this element is regarded as necessary to the work rather than as a decorative addition. Finally, by binding the work into a single unit made up of highly individualized modules, she invites the viewer to become more conscious of the play of similarities and differences among the constituent parts.

Beginning with Edouard Manet, modern painting was born in the maelstrom of urban development. White is an urban artist. The connection to Manet isn’t as farfetched as one might think. In his paintings, Manet recognized the isolation of each element from the others — such as the nanny, young girl, grapes and sleeping dog in The Railway (1888). Each inhabits its own world. This is also one of the identifying characteristics of White’s work — every mark and image hold its own, down to the abstract fuchsia scribble hovering in a dark blue atmospheric field.

Wendy White, “El Rocko Lounge”, (2012), acrylic on canvas, digital print on vinyl over metal frame, 103.5 x 139 x 4 inches

Today’s city is a hodge-podge of self-sufficient fragments. Nothing really goes with anything else, and yet it all does somehow fit together and bump along. Cacophony rules. And in that dissonance White sees the conflict between anonymity and particularity, as well as the written signs of opposition written in graffiti tags. Despite the state of deterioration we inhabit, or perhaps because of it, the desire to overcome invisibility and conformity manifests itself in many small and discrete ways.

Painting seems the perfect medium for White’s project since institutions largely disregard it — it is, one might say, a kind of graffiti that some curators feel it’s their duty to remove from the walls.