For Photographer Ann Shelton, the Japanese Art of Floral Arranging is a Medium for Messages.

Pōneke/Wellington-based photographer Ann Shelton’s personal ikebana-inspired revival has resulted in some astonishingly beautiful works. Like all good images, they can be appreciated in and of themselves, but there is an interesting story behind them.

One chilly morning, a taxi driver and I negotiate our way into the hills beyond Wadestown to Wilton, where Ann lives with her designer/art director partner Duncan Munro in a 1957 home designed by Czech-born architect Frederick Ost. In 2020, the couple won the Resene Total Colour Heritage Award for the spectacular transformation of the house, having restored much of the interior colours back to their original vibrant palette, and the place is a joy to enter. On the dining table are a number of vases bursting with camellias in disarray. Long, glass-fronted cupboards upstairs store a collection of ikebana vessels made by Ann over many years. In a converted garage below the house is Ann’s studio.

It all started back in the mid-1970s, when Ann, then aged about seven, was first encouraged by her mother to enter flower-arranging competitions in the Timaru Horticultural Society Show. “It was the usual stuff to start with — you know, sand saucers, that kind of thing,” she says. “I won some prizes and gradually moved through the floral art sections of the show. Mum tells me I did do some ikebana-style entries, which she taught me the principles of from a book.”

Later, when Ann’s side hustle as a rampant op-shopper was in full swing, she began to collect Ikebana International magazines — widely read publications that were being discarded after the post-war craze for Japanese flower arranging had begun to wane in New Zealand. “I carried them from one grotty flat to the next, thinking I’d eventually make use of them,” says Ann. “The bright colour fields that formed the backgrounds of the photos of arrangements in the magazine have always been in my works, from Redeye to Jane Says. I guess that’s where they came from.”

“It was the usual stuff to start with — you know, sand saucers, that kind of thing.”

Ann enrolled in classes in which the students were taught with Sogetsu School ikebana books and exercises. “So every Saturday morning, I’d cut down half the backyard and arrive at the classes with bits of branches from the semi-forest behind our house,” she says. “I may have gone a bit overboard!”

Later, while at Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts in 1992, she made a trip to Japan as part of the Hiroshima cultural exchange. Staying in Tokyo for around six weeks after an exhibition in Hiroshima, she was able to explore Japanese culture, including ikebana, first-hand.

“Ikebana slows you down,” she says. “Because of its spiritual roots, it teaches you to engage with nature in a thoughtful way, not just decoratively or for purposes of display. Although I can’t claim to be an ikebana-ist, I owe a great debt to ikebana because it encourages a different relationship to nature. I’d grown up with an attitude in which plants were valued primarily as commodities and for their aesthetic value. My new approach meshed with what I wanted to do in my photographic work: to ask how we can reformulate or realign our relationship with nature, to see ourselves inside it.

Vessels in Ann’s collection. She elaborates on the link she sees ikebana having to photography: “For instance, I might look at a stem of camellia and remove everything except the flower and a single leaf; similarly, I might crop an image to exclude a detail I don’t think works. That’s the hardest thing I find with composing an ikebana-inspired arrangement — the risk lies in going too far. You can’t put a leaf back on. The aim is to concentrate, to focus precisely on what is to be foregrounded.”

Vessels in Ann’s collection. She elaborates on the link she sees ikebana having to photography: “For instance, I might look at a stem of camellia and remove everything except the flower and a single leaf; similarly, I might crop an image to exclude a detail I don’t think works. That’s the hardest thing I find with composing an ikebana-inspired arrangement — the risk lies in going too far. You can’t put a leaf back on. The aim is to concentrate, to focus precisely on what is to be foregrounded.”

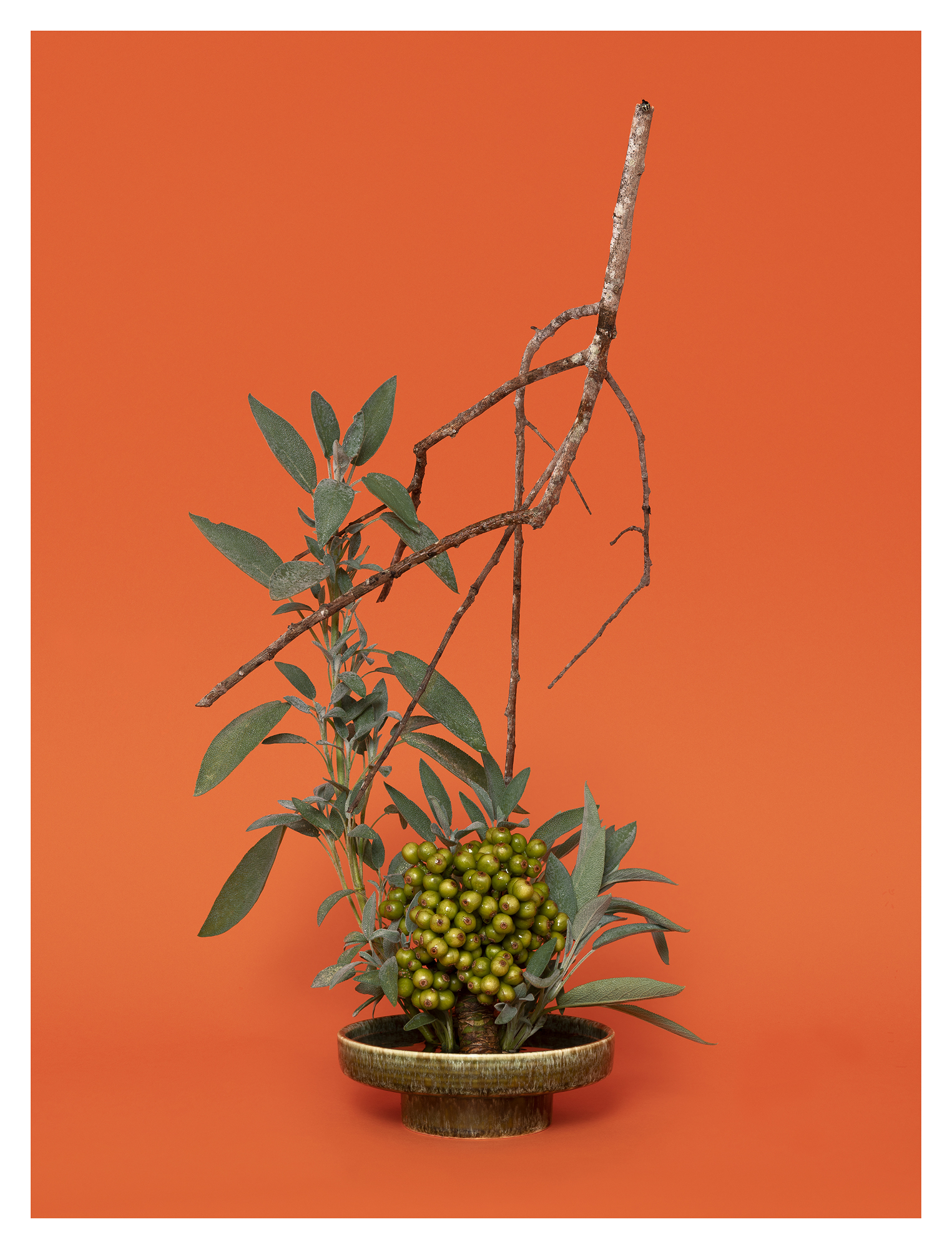

The Mother, Rue (Ruta sp.).

“In a way, ikebana is also conceptually linked to photography,” she continues. “As I understand them, both are concerned with a distilling down and paring back, a removal or cropping out of elements in order to articulate a fragment from the world visually, or to engage with a significant aspect of a plant or group of plant attributes.”

Then there’s the matter of imperfection. When foraging, Ann will sometimes pick leaves that are full of holes, rejecting perfectly formed glossy ones untouched by insects. “It’s not always a matter of the perfect bloom, but instead of nature in transition,” she says. “It’s a natural progression.”

Ann is also interested in the gender politics of flower arranging. She points out that ikebana was a creation of Japanese Samurai male culture at the same time as, and as a part of, the tea ceremony. It was a solemn, thoughtful cultural practice undertaken by men. “But by the late 19th century in Britain, flowers had become the province of women, who in the West, were also confined domestically. If you think of the [late 1800s, early 1900s] painters Berthe Morisot or Mary Cassatt [leading talents in the Impressionist movement], theirs was primarily an art of domesticity, pursued with great determination in the face of general societal disapproval.” Berthe’s teacher actually warned her parents that if he continued to work with her, she would become a painter, and therefore unsuited to the role of wife and mother.

British photographer Julia Mary Cameron, a woman with six children, was given a camera when she was 48, in 1863. In the teeth of opposition from the photographic establishment, she carved out a significant reputation for herself. “I like to think of myself as having a conversation with that gendered history and valuing it,” says Ann. In her series Jane Says, Ann’s artworks step away from ikebana in the purest sense. These works take on a looser and less-structured configuration that’s nonetheless influenced by the Japanese artform. Her ikebana-inspired photographs also mine the way in which plants have traditionally been used as a means of controlling female reproductive health. This is the critical nexus for Ann, who draws a link between the controls applied to the plants and those acted on the body.

“In making ikebana, the first thing you learn is to look at the plant, the direction or flow of the stem. It’s not just a case of picking at random because things might look pretty together.”

Her large 2020 image The Mother, Rue (Ruta sp.), featuring kawakawa, for instance, uses the native plant recognised by Māori for its efficacy in treating cuts and wounds. In her image, falling kawakawa leaves are combined with more upright rue, a Mediterranean herb that was used in Roman times to induce abortion, as well as to repel insects. First seen in 2016 in the exhibition Dark Matter at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Jane Says is an ongoing body of work numbering nearly 20 now that has been eagerly responded to, especially by women who remember the 1987 song of the same name about a young girl taking control of her life.

Ann looks carefully at an unusual ikebana pot made in 1990 by Bruce Martin, which I’ve just collected from auction house Dunbar Sloane. She selects a camellia branch with six flowers on it, the aim being to combine them to make a composition of flowers and young, barely budding magnolia twigs. With the deftest hand, she rapidly transforms its bronze, geometric, offset, double-square structure into a series of graceful floral curves. Rules are broken; she removes two of the flowers, leaving four (ignoring the Japanese preference for odd numbers), and places one of the magnolia fronds upside down in the vase.

After sitting in front of it for a while, Ann says, “Mmm — that’s lovely. It should do.” We go down to the studio to photograph it and I promise not to divulge her technical secrets.

A couple of days later, she emails me the image. The pink of the camellia is perfectly set against a cinnamon-brown background. Despite the use of a challenging pot, the artist’s experience and deftness of touch has ensured that an arrangement that took no more than 10 minutes to make has all the timeless beauty, grace and elegance of a classic Japanese still life.

Ann’s composition in Peter’s vase by Bruce Martin. Ikebana “is less to do with originality or creativity in the beginning and more about following the principles to achieve the correct result according to the ikebana style,” says Ann of her early days as a student of the art. “You learn to think about composition, line, colour, mass and space. You learn how far above the top of a particular pot your highest stem should be, and next come the angles and heights of the following branches. You learn about the removal of unsuitable buds, the trimming of leaves and ‘crimping’ or folding of plant material, including the manipulation of the stems of plants. You concentrate single-mindedly on the task at hand.”

annshelton.com