Amir H. Fallah: Better A Cruel Truth Than a Comfortable Delusion

by Paul Laster

Best known for his unique approach to portraiture, Amir H. Fallah has made a name for himself not by painting incredible likenesses of people but by revealing who they are through the objects that they possess. Exploring issues of family, identity, and representation, the Tehran-born, Los Angeles-based artist has made several series of colorful, collage-like paintings in which the sitters are shrouded in patterned fabrics amid their most prized possessions. Beginning with commissioned paintings of collectors who collaborated with the artist on the choice of objects, Fallah’s portraiture subsequently delved into the lives of immigrants in Southern California. Since 2019, however, Fallah’s practice has taken a turn toward the appropriation of found images—which he has been compiling in a database— to explore his personal history. At Denny Dimin Gallery, his exhibition “Better a Cruel Truth Than a Comfortable Delusion,” featuring eight new canvases (all 2020), offered a variety of visual narratives with images, symbols, and objects that speak to the artist’s lived experiences. Each painting started with a lesson on the complexities of life that Fallah wanted to pass down to his five-year-old son. Better a Cruel Truth Than a Comfortable Delusion, the first painting in a rhythmically laid out show, combines a gesturing, black-cloaked woman—whom he thought resembled a judge—from an Art Deco-style Erté drawing with a smiling Hare Krishna Jagannatha sticker, a Persian miniature of two mirrored angels holding geometric abstractions, his son’s anatomy drawing of the circulatory system, and other found or photographed images. Arranged like pieces in a jigsaw puzzle, the imagery references the artist’s past and aesthetic influences, as well as his interest in multifaceted forms and realities.

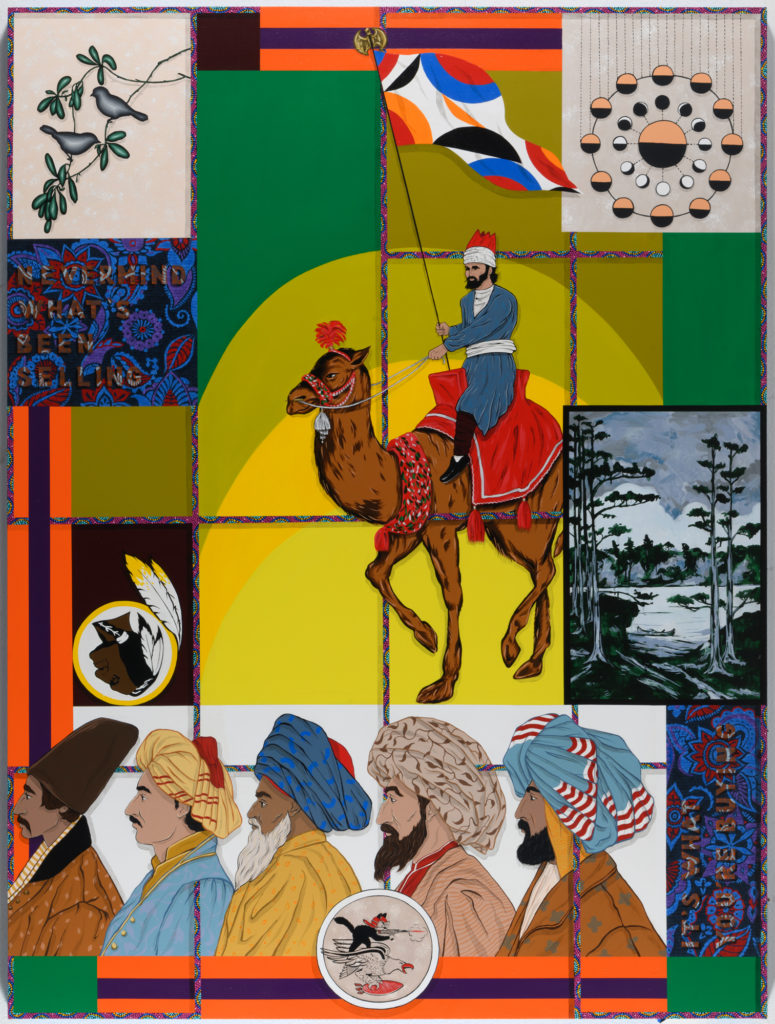

Most of the canvases feature painted images of rugs that appear to have the artwork titles woven into them, as in Nevermind What’s Been Selling, It’s What You’re Buying. The work is named after a lyric in a song by the political punk band Fugazi, which Fallah listened to as a teenager. Off-center, a man on camelback holds a flag in the style of a Frank Stella abstraction; the figure relates to Fallah being called a “camel jockey” by his Islamophobic classmates. The upside-down Washington Redskins’ logo represents his favorite sports team in his youth, although he resented the racist imagery, and the five Muslim men at the bottom symbolize the way his high school teachers stereotypically thought most Iranian males still dressed.In Dying for Invisible Lines, Killing for Invisible Gods— which gestures to the violence of borders—a woman holding a symbolic key to the city crosses the decorative lines that section the canvas, both stepping over and staying within the boundaries. Resembling a character from an old advertisement, she flashes a mischievous smile as she marches forward brandishing the giant beflowered key. Behind her are a caged man, a sorcerer, and a dark sky full of shooting stars, yet a happy young girl relishing nature and a welcoming sunflower lie ahead, suggesting a more optimistic future for his multiracial son in an unbiased America.

Two new tondos in the show, Hold On Tight and Beast of Burden, fit another variety of canvases that the artist first introduced in his 2020 solo show at Los Angeles gallery Shulamit Nazarian, “Remember My Child . . . ” where the self- referential paintings also made their debut. Shaped like the Earth or a portal for the viewer to enter the artist’s world, the edges are painted and collaged with a global assortment of flora and fauna, enchantingly entangled with cultural symbols that have influenced Fallah. In Hold On Tight, Uncle Sam on a rocket from a Soviet anti- American poster is caught opposite an angel from a Persian miniature presenting a crown. On the top left, a feminist protest sticker portrays the Statue of Liberty clenching her fist, while other commercial imagery and patterns pop in and out of exotic plant life. A mix of high and low, old and new, and East versus West symbolism, the painting—like all of Fallah’s fascinating artworks— metaphorically captures the immigrant experience in both its splendor and grief.