How Revenge Shopping Inspired Artist Amir H. Fallah’s New Hong Kong Show

Words by AAINA BHARGAVA | April 12, 2022

Revenge shopping and navigating a third-culture identity inform Amir Fallah’s first show in Hong Kong

As for many of us, the highlights of lockdown for artist Amir Fallah were mealtimes and receiving packages containing online shopping—the latter event so much so, it sparked the idea behind his first exhibition in Hong Kong, Joy as an Act of Resistance at the newly opened Denny Dimin Gallery in Wong Chuk Hang. Recently, he says, “I came across an old image of a smiling woman with shopping bags; it reminded me of Amazon boxes that show up at your house or when you get food deliveries. These are moments of temporary joy you find in absolute misery.”

Between the pandemic, civil unrest, intense elections around the world and rampant wildfires, there has certainly been a lot to be miserable about in recent years. For Fallah, finding small moments of joy was “a way to fight this non-stop wave of bad news, bad feelings and dread”. Perhaps choosing to feel joy as an act of resistance is just the antidote we need.

It was after the conception of the show that Fallah encountered revenge shopping—a phenomenon revived due to the pandemic of splurging on goods to make up for the lack of travel and recreation. Fallah captures this idea, and the feeling of contentment a new purchase brings, in the exhibition’s namesake painting. A luxuriously dressed woman overloaded with shopping bags and gift boxes emerges as the central figure in Joy as an Act of Resistance. Unlike his previous works, the character’s face is visible here.

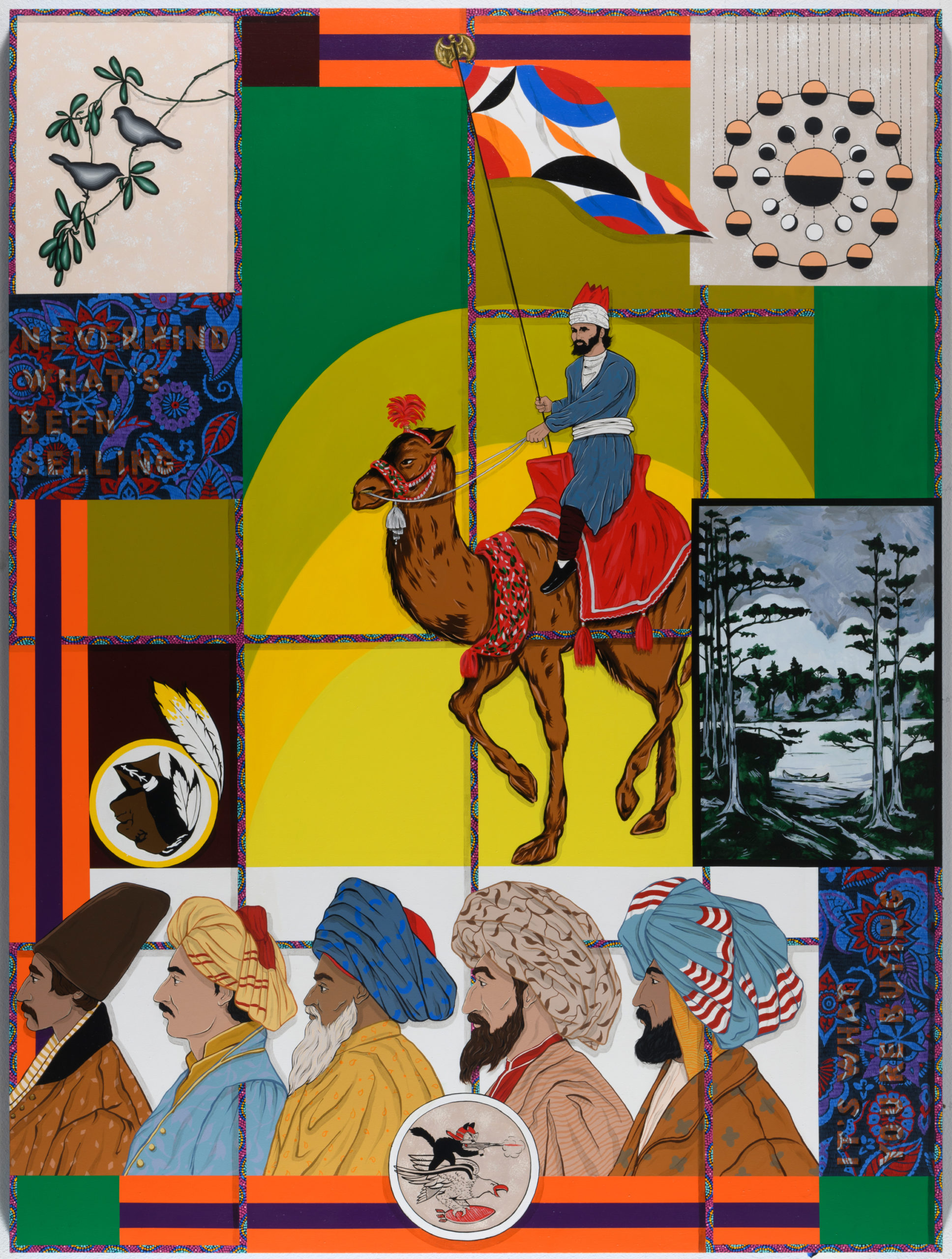

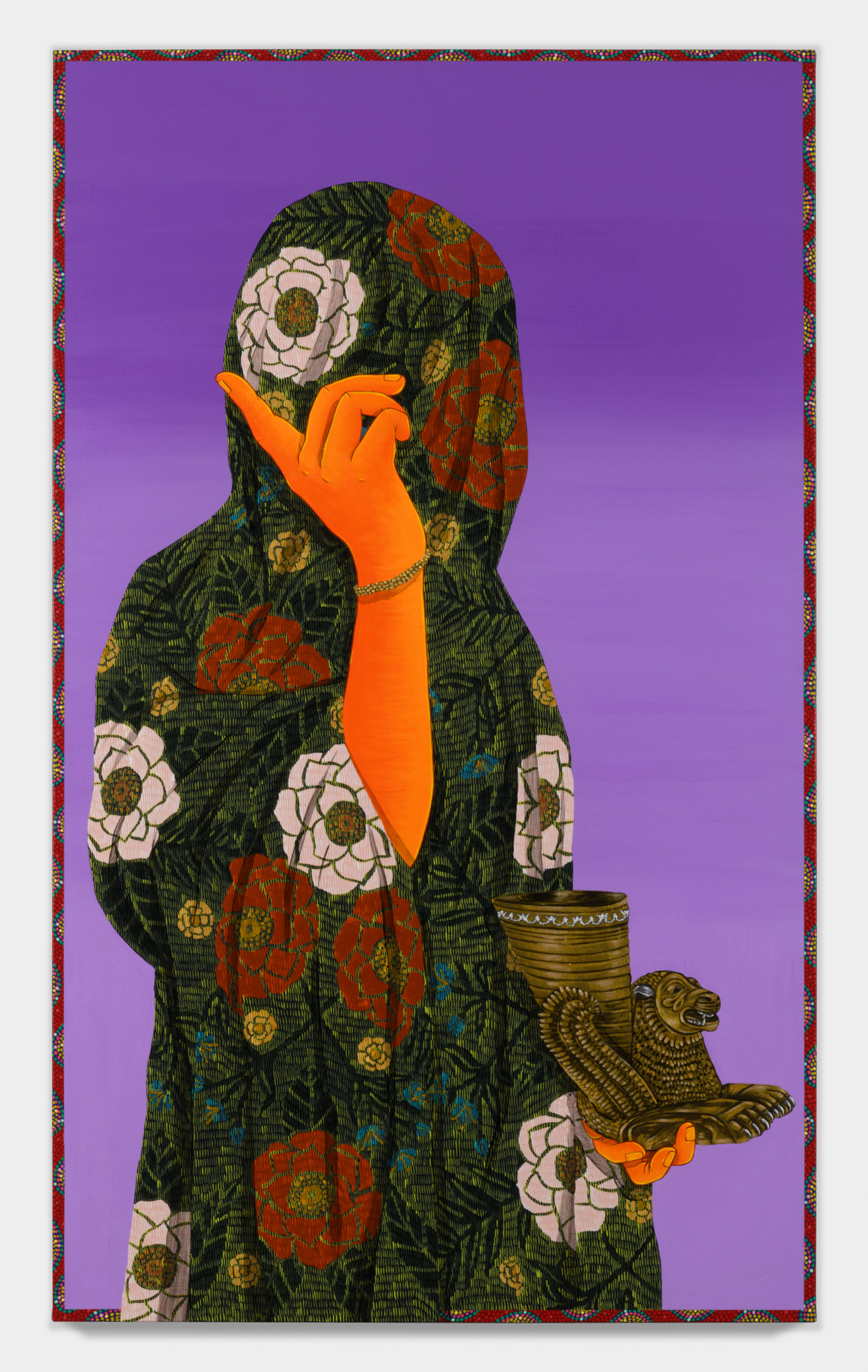

Fallah’s best-known works are his portrait paintings, which are typically characterised by bright colours and intricate details, and feature a signature collage-like aesthetic and “veiled” subject matter. Well known pieces such as Offerings at the Altar (2017) and A Distorted Reality is Now A Necessity To Be Free (2019) depict figures with a cloth draped over their head covering most of their body, often surrounded by or holding objects which hint at their identities. This way Fallah reveals the subject’s identity without relying on their physical features, as seen in The Way (2022) and The Artifact (2022), two new works featured in the Hong Kong show.

ABOVE Fallah’s A Distorted Reality is Now a Necessity (2019), Photo: Denny Dimin Gallery and the Artist

ABOVE Fallah’s A Distorted Reality is Now a Necessity (2019), Photo: Denny Dimin Gallery and the Artist

Fallah’s personal experiences and feeling that he is suspended in a cultural limbo inform his desire to define identity beyond physical appearance. He was born in Iran, but his family left while he was young; he lived in Turkey for two years, then a refugee camp in Italy for three months, before arriving in the US at the age of six. He recalls having to learn three or four languages before the age of seven. “I was airdropped into different cultures, but I just adapted.”

His sentiments on arrival in America resonate with immigrants universally. “There is a little bit of trauma associated with learning to assimilate into American culture and fit in,” he says. This can be compounded when people are constantly asking you where you are from, with the unspoken question being “What are your race and ethnicity?”.

ABOVE Fallah’s Offerings at the Altar (2017), Photo: Denny Dimin Gallery and the Artist

ABOVE Fallah’s Offerings at the Altar (2017), Photo: Denny Dimin Gallery and the Artist

Like with many third-culture kids, Fallah doesn’t have an easy answer. In the States he isn’t really considered “American”, and in Iran he is seen as more American than Iranian, because of his accent and the way he dresses. “It’s not negative thing,” says Fallah. “I’m a cultural hybrid.” Having lived in Los Angeles for more than 20 years, he feels very at home with Mexican culture: “Every day I interact with Mexican culture, from the food I eat to the people I hang out with … I felt much more at home [during a visit] in Mexico City than I do in Iran,” he says.

Considered a very ‘dark skinned’ Iranian, Fallah is often mistaken as being Indian or Mexican. His wife who is Puerto Rican has red hair, pale skin, and freckles. “She looks more like Molly Ringwald than any Puerto Rican you might have seen,” says Fallah. “Now we have this Iranian – Puerto Rican kid who looks like we kidnapped someone’s white baby.”

These incidents of misidentification inspired the artist to visually challenge the way we perceive identity. His most personal works are “portraits of belief systems—it’s about me and my wife and what we believe”. They serve as a legacy he wishes to leave his son, and to remind him “of how they want him to navigate the world”. After the birth of his now six-year-old son, Fallah realised that many children’s stories are fables used to teach life lessons; he wants his paintings to function in a similar way.

Each of his works begins with text, whether that’s lines from Persian poet Rumi or a book he read recently, a phrase he overheard or song lyrics. The text serves as a visual prompt for the selection of images he makes, which function like jigsaw puzzle pieces coming together to form a bigger picture and message.

Heavily ornate and detailed, his paintings are made up of elements drawn from a diverse range of sources. He begins by creating archives of images from Instagram, Flickr, Facebook, Pinterest, random Google searches, museum databases, public archives and copyright-free databases. He then mixes all this imagery together, reflecting his visual influences—ranging from art history and graphic design to pop culture-—to create an opulent and seductive aesthetic. This is best exemplified in the largest work on view in the Hong Kong exhibition, Angel’s Trumpet (2022). Details include an angel from a Persian miniature on the left and a copy of 1960s minimalist and abstract artist Frank Stella’s painting on the left, while at the top is a vintage illustration of idyllic sand dunes in the Middle East.

The sumptuous details and saturated, bright colours are meant to draw viewers in. “Once I can seduce the viewer into looking closer, the piece reveals itself to be about something more serious,” says Fallah. “I think about how to seduce the viewer a lot. How do you create a painting that even people who dislike the style will want to press their nose up against?”

Amir Fallah’s exhibition at Denny Dimin Gallery runs until June 4th