Ann Shelton

In Conversation with Casey Carsel and Laura Thomson

March 3, 2017

Through a wide range of photographic investigations, Wellington-based artist Ann Shelton has, over her 20-year career, explored the construction of narratives that surround social, political and historical contexts. A selection of Shelton’s prolific practice has been brought together in her review exhibition, Dark Matter, at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, which opened on 26 November 2016 and continues through to 17 April 2017.

While studying photography at Elam School of Fine Arts in Auckland, Shelton decided to turn the camera on herself and her friends, presenting a slice of New Zealand’s 1990s urban culture through images of the infamous Karangahape Road scene in Auckland. In one image, a young man with nose and lip piercings wears a suit, with white flowers on his lapel and a silver scarf around his neck. He sports a buzz cut and heavy makeup that makes his face appear almost pure white against his drawn black eyebrows, heavy eyeliner, mascara, and red lips. He playfully stares the camera down, and looks as if he might burst out laughing at any second. Another image shows a white-tiled sauna room with soap dispensers on the wall. In the centre of the room stands a black-tiled column with a showerhead on two sides. These photographic explorations of Shelton’s social scene form a series titled ‘Redeye’ (1997), presented in Dark Matter as six large-scale—and larger than life—photographs that lean against two orange walls.

Following on from ‘Redeye’, Shelton began directly investigating ideas surrounding the complexity of historical memory, transitioning from the study of individuals to the traces that individuals leave on a place. Her series, ‘in a forest’ (2005-ongoing), for example, documents trees that are the product of seedlings presented by Olympic Committee members to the 130 gold medalists at the controversial 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany. In the exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery, 26 images of these trees are presented in a two-tiered frieze. The walls are painted a pale sky blue. In the bottom layer of the frieze, the 13 trees of the top layer are turned upside down and their order reversed, forming a mismatched mirror to their upper counterparts. In her essay on the image, Dorothée Brill notes its engagement with photography’s blur between fact and fiction. The combination of a simple, clean documentary style with the historical context in which these trees were gifted, traps the viewer between the subject they see and the events that occurred in bringing them into existence.

Exhibition view: Ann Shelton, Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (26 November 2016—17 April 2017). Photo: Sam Harnett.

In ‘Public Places’ (2001-03), a series of images of unpopulated natural scenes, Shelton continues to explore the contrast between photography as a tool for documentation and as storytelling. These images appear in pairs: to the left, a photograph of a place, and to the right, the photograph’s mirror image. In each place, fictional or non-fictional crimes involving women are said to have occurred—events that were turned into more gruesome horror stories when they were retold in popular culture. In an essay about the series, accompanying a 2003 publication of the same name, Shelton described these scenes as split between geography, history and form. The viewer imprints the drama onto an empty site, reads the evil in the banal, and recreates the myth once more.

In her most recent series, ‘jane says’ (2015-ongoing), also included in the exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery, Shelton presents photographs of rich botanical arrangements based around her research into plants’ historical uses for both fertility and birth control. The series is one of the few instances in Shelton’s career of the photograph not being of an existing scene, and is perhaps the most designed and staged manifestations of this choice. Each photograph is titled with a trope of womanhood and the plant it presents—for example, _The Hysteric, Fennel (_Foeniculum sp.) (2015-16). This act of naming expands on a relationship Shelton has cultivated in her practice between identity, perception and context, as well as on the way in which the female body is performed.

At Auckland Art Gallery, ‘jane says’ will be accompanied by The physical garden (2015-ongoing): a free performance held on various dates throughout the exhibition. In The physical garden, two young women perform a series of quotes surrounding the historical research that has informed ‘jane says’, serving to activate the extensive research on which these photographic works are based.

In this interview, the artist, who is associate professor in photography at Massey University, Wellington and chairperson of Enjoy Public Art Gallery, discusses her Auckland Art Gallery exhibition. She talks about her continuing investigation into photography as a medium in which identity can be explored in figurative as well as non-figurative bodies, and the viewer’s part in creating meaning out of what is given.

Exhibition view: Ann Shelton, Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (26 November 2016—17 April 2017). Photo: Sam Harnett.

CT: Could you explain the thoughts behind Dark Matter, the title of your exhibition at the Auckland Art Gallery?

AS: Dark matter is the tangible influence of invisible forces: the material out there in the universe that affects us but remains invisible to our eyes. My photographs speak of the influence of invisible forces—of narratives, events, and people. While the works are often empty of people, aside from in my early work, they are full of content. When I came up with the title Dark Matter it stuck, as it has both a conceptual and—more directly though my ongoing interest in traumatic stories and violence as subjects—a content-driven relationship to my work.

It is interesting to consider Western culture’s privileging of sight and the ongoing belief that seeing is everything and should be privileged over other senses. You can see the reoccurring unpacking of sight and seeing within my work as a critique of that privileging, and as a broad sustained subtext in my practice as a whole. I am trying to look deeper and on more subjective terms at the construction of meaning in our particular cultural context. My images address the ‘dark matter’ of our history, and often that’s a New Zealand history; but equally as often it’s a history that reaches out globally and has global resonance. The impact of colonisation, feminisms, identity politics and constructions of gender, disease and critiques of technology, surveillance and high capitalist culture are all subjects in the work. Alongside that content runs an ongoing interest in photography’s relationship to the construction of meaning, including, its hidden affects, its doubleness as both a force for agency but also a mechanism of power and of hidden agendas and influences, its strong links to vision, and my interest in how pre- and post-photographic apparatus have informed and constructed the way that we see the world.

Exhibition view: Ann Shelton, Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (26 November 2016—17 April 2017). Photo: Sam Harnett.

CT: With such a large body of work to choose from, how did you decide on what to include in Dark Matter? What was it like to see works that span your prolific 20-year practice come together in the same space?

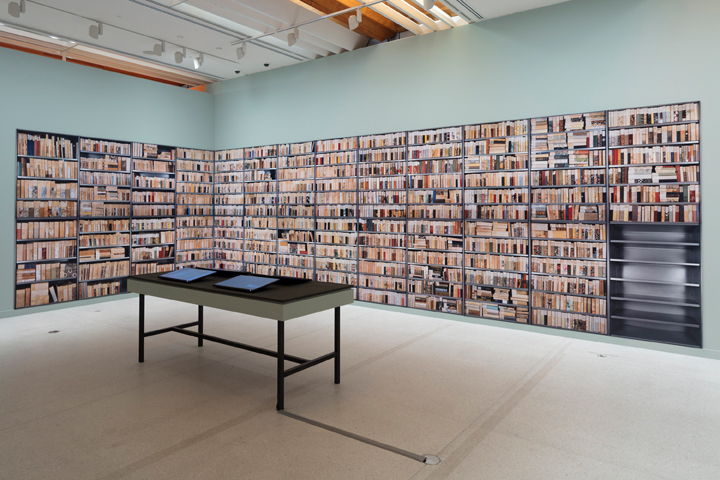

AS: A lot of works that were in my original selection ended up on the cutting room floor as it were, because of space restrictions; but also because they didn’t work in the wider exhibition conceptually. The curator Zara Stanhope and I worked together, thinking through the relationships between bodies of work. Zara brought some fresh curatorial ideas to how we grouped each section of the exhibition—we have known each other and made exhibitions together for over 20 years, so we had a lot of ground covered. We met and trawled through my archive on several occasions, looking at unpublished and lesser-known work and considering how each grouping of work functioned in the frame of the show. We wanted previously unpublished bodies of work to feature in the exhibition, alongside those precious opportunities that a large space like this offered to present ambitious showings of some bodies of work in installation form, such as ‘in a forest’ (2011-ongoing) and ‘a library to scale’ (2006). We also recognised the accompanying book could be its own entity, including works that were not in the exhibition, and having its own logic and conceptual relationship to my practice.

I also introduced an approach to the conception of the space where we started out with a grouping of arcades that morphed into rooms and channels. These were connected via my introduction of scenographic paint finishes, which ease you from one room to another through a kind of bruised painting effect on the walls, thanks to the work of exhibition designer Scott Everson and scenographer extraordinaire Eric Knoben. Some people miss these paint finishes, but for the viewer who takes their time, a little reward awaits. I am attempting to draw analogies between photography as a kind of bruise or impression left behind on the film or pixels, and relating that to a sense of bodies holding the impression of memory or of events that circulate throughout my work. As photography becomes a much more intangible medium, less based in prints and more in pixels and on tablets and screens, it loses its ‘bodiliness’. And that brings us back to ‘dark matter’—the tangible influence of less tangible or physical forces.

Exhibition view: Ann Shelton, Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (26 November 2016—17 April 2017). Photo: Sam Harnett.

CT:You started out as a photojournalist before turning to photography in the fine arts. In both cases, what led you to choose photography as the medium to devote yourself to?

AS: I guess this ties into my answer above. For me to maintain an interest in photography, it had to be a compelling and manifold vehicle for meaning; it had to have all those layers. As I mentioned earlier, I am interested in the places where photography falls down; where it has been implicated and is fallible. All those ‘chinks in its armour’—those are the places where I have felt compelled to engage with it and that, I think, is what has kept my interest for so long. Those doubled and contrasting aspects of the medium are paralleled in the content of my work and allow me to dovetail formal and conceptual concerns across images.

CT: Given your background in photojournalism, could you talk a little bit about your perspective on photography’s dual potentials—its potential to report fact, and its potential to create stories and narratives as art?

AS: For me, veracity can be located at both ends of this spectrum. Journalism is a crafting of materials that edits and refines and presents certain perspectives, as does any fiction. I am interested in that middle ground: that messy space where fact and fiction conflate and where any sense of truth is complicated, particularly within the context of photography as a medium.

In terms of my images, works like ‘jane says’ and ‘Public Places’ are investigating the edges of fact and fiction through my interest in urban myth and how stories come to be read as real through their repetition across time. In many ways, the status of journalism is the dangerous one in the binary pair you present, as it appears as fact and is culturally inscribed as such, but it’s not that simple. Of course, journalism is affected by the forces that produce it and their interests. In terms of art practices, many artists, Joachim Koester and Tacita Dean among them, share my interest in exploring the complexities of the territory between fact and fiction. In many ways, this is the spectrum that has informed my career; the contradictions herein have interested me ever since I first read Susan Sontag, and then Abigail Solomon-Godeau on Sontag. In her landmark 1994 essay ‘Inside/Out’, Solomon-Godeau stated ‘…I would nevertheless suggest that the terms of this binarism are in fact more complicated. …On the one hand, we frequently assume authenticity and truth to be located on the inside (the truth of the subject), and, at the same time we routinely—culturally—locate and define objectivity (as in reportorial, journalistic, or judicial objectivity) in conditions of exteriority, and non-implication.’ 1

Exhibition view: Ann Shelton, Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (26 November 2016—17 April 2017). Photo: Sam Harnett.

CT: It was your 1997 ‘Redeye’ series that first put you in the limelight of the Auckland art scene. Could you trace the connections between that series’ exploration of identity and representation, and the consideration of similar themes in ‘jane says’? What do you think is photography’s role in the representation or creation of identity?

AS: I guess we are in a ‘post-photographic’ moment in which imagery has morphed into a hyperreal space where manipulation and retouching are the norm. The consumer end of this photographic space shares its intent with this moment we find ourselves in: a high capitalist consumer culture that wants us to buy more stuff and aligns ‘having’ with being individually fulfilled. So this is one of the places we need to be vigilant with photography and how it’s operating. However, photography can also allow us to access pluralised and diverse identity positions and meanings in both figurative and non-figurative approaches. I am interested in how photography can be a space for generating a plurality of meaning and where multiple positions can be opened up, and in how the viewer can have an active role in creating those meanings. I am hoping to achieve some of this complexity, or at least to allude to it and to the viewer, through various prompts: a sense of the absence of bodies leading to a consideration of bodies outside figuration; the height at which the works are hung, ideally low, to allude to a body and echo a human-scale viewpoint; the arrangement of the works in large and complicating groups; the titles which refer to specific and generic female characters; the intense suggestion of surface and depth in the work; and other materials in the form of texts or performances that accompany the works.

CT: As well as being a practicing artist, you are an associate professor at Massey University’s Whiti o Rehua School of Art in Wellington. How have your experiences as an academic and educator influenced your practice?

AS: I am an academic at a very exciting art school moment. We have the first Māori woman head of an art school in Aotearoa New Zealand, Dr Huhana Smith, and I suspect we have one of the largest cohorts of indigenous academics in an art school, in their own country of origin, anywhere in the world. This is something I want to be part of, and so for me that’s what makes my job exciting at the level of leadership. I believe we all have to take responsibility for addressing the theft of economic resource from Māori historically, and I see being part of an art school such as Whiti o Rehua School of Art—linked also to Toioho ki Āpiti, Massey’s Māori Visual Arts programme—and the meaning it creates for young people as working toward some of the changes necessary to acknowledge this theft, and populate Māori into more leadership positions.

Working with students is always a privilege, and many of them become friends and colleagues. I am also fortunate to support young people as they develop their careers and enter the art world through my involvement with Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Wellington’s longest running artist-run space. We give many young artists their first exhibition. It’s also great to see the current revival of interest in identity politics among young artists, and some of the same urgency and creativity around that material that was a salient characteristic of the 1990s and the art scene I was part of at the time on Karangahape Road in Auckland.

In terms of links, these concerns link back to my own work. Questions around who creates meaning, who gets to speak, and how photography is implicated in those moments when meaning is created are foundational for me. These moments of exclusion, of failure or break down are the moments I want to look at as an artist.

Exhibition view: Ann Shelton, Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (26 November 2016—17 April 2017). Photo: Sam Harnett.

CT:How do you choose the research topics you pursue?

AS: For the last eight years, I have been fascinated by plants and their histories, the way human activity has attempted to control plants and exploit them, and the way we have lost touch with them. My work has looked at narratives around plants that link them to some dark moments in European history (in a forest), and to the ways that knowledge around plants has been lost, as in ‘jane says’, appropriated by industry, or wilfully excluded from the canon by Western botanists—as was the case with some plants relating to the control of fertility. Currently I am working on a new project, which concerns plant history, but in this instance, the plants were transformed into another physical form some time ago.

CT: Could you tell us about The physical garden, the performance that will be staged on 26 February, 12 March, 1 April and 16 April 2017 as an accompaniment to the work ‘jane says’?

AS: Historically, the physical garden was a precursor to the botanic garden. Sponsored by wealthy medical doctors, the physical garden was a garden of plants for use in medicine. The images in ‘jane says’ are a kind of photographic garden of these medical plants. The works link photography and botany, and the impulse to record specimens and their uses from around the globe. They are my small physical garden if you like. The performance presents a viewer with glimpses into the historical context for these works: tracts of information, not unlike Walter Benjamin’s ‘Arcades Project’ (1927-1940) which was published unfinished as a kind of stream-of-consciousness list of related quotes which were assembled into common themes. The physical garden is also a list of quotes—covering everything from the now-extinct giant fennel plant that was traded for more than the price of gold and harvested to extinction because of its popularity as a contraceptive, to our very own poroporo plant, farmed commercially briefly in Taranaki, Aotearoa New Zealand, to be used in contraceptive pills. The physical garden performance allows me to present to a viewer all of those swirling pieces of content; all the background research that a photograph cannot speak. Hopefully it allows me to get to the depth of the works across and provide an insight into them, creating order and juxtaposition through them, not unlike the way you would in an essay or a piece of writing.

Exhibition view: Ann Shelton, Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (26 November 2016—17 April 2017). Photo: Sam Harnett.

CT: What was it like watching others perform with your work?

AS: It confused people that I asked others to perform my work. For me, I don’t see this as anything out of the ordinary; it’s part of my artistic toolbox. Like any aspect of the work, who performs it is carefully considered. —[O]

—

1 Abigail Solomon-Godeau, ‘Inside/Out’, in Public Information: Desire, disaster, document (San Francisco Muum of Modern Art, 1994), 51.

Professor Abigail Solomon-Godeau will give the keynote presentation (at 6pm on Friday 31 March) for ‘Agency and aesthetics: A symposium on the expanded field of photography’ (Fri 31 Mar 2017 — Sat 1 Apr 2017). The symposium is convened by Ann Shelton and Dr Zara Stanhope, in association with the exhibition ‘Ann Shelton: Dark Matter’