NEW YORK – DANA SHERWOOD: “CROSSING THE WILD LINE” AT DENNY GALLERY THROUGH FEBRUARY 21ST, 2016

By J. Holburn, January 20th, 2016

Dana Sherwood’s conceptual focus is the Anthropocene, a contentious term which in essence describes our present and future epoch, framed by the destabilization of nature as impacted by human activity on earth. With a practice that spans drawing, video, and sculptural installations, her work intervenes to engage local wildlife and open up a realm of play between humans and animals. Just as Joseph Beuys instigated a political party for animals back in 1974, Sherwood has hosted a dinner party for animals, using her skills as a former baker to create decorative, decadent meals to entice her guests, ultimately presenting the results at Denny Gallery in New York.

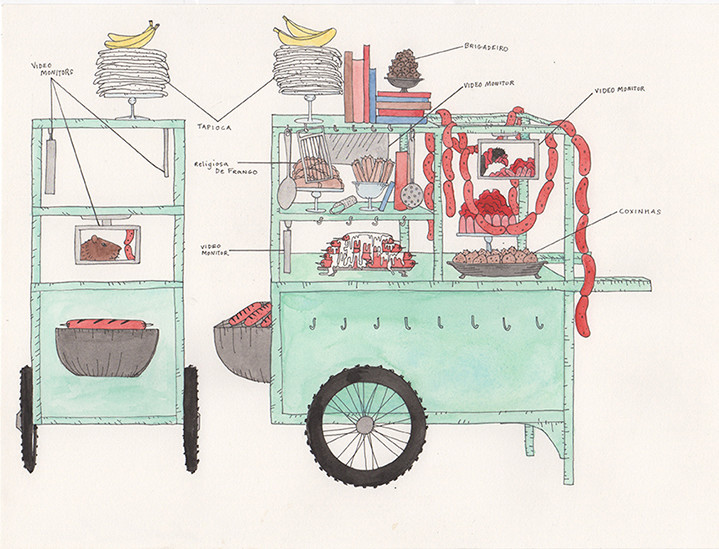

Like Beuys, Sherwood is attentive to the sensory experiences and intuition of animals, establishing a conversation with them through elaborate food aesthetics. The animals are her collaborators, co-conspirators and meaning makers. The central sculpture of the exhibition is a reincarnation of an elaborate food cart originally located in the Botanical Gardens of Brazil. Titled Crossing the Wild Line, the cart is adorned with cooking utensils, books, raw meat and fish, and is accompanied by a screen documenting the process of decaying meat and other activities around the sculpture.

Her book selection displayed upon the cart features a selection of cook books and other texts including Tracking & The Art of Seeing by Paul Rezendez, The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan, and Donna Haraway’s When Species Meet. Haraway in particular contends that the practice of eating is the site where human and nonhuman ways of living are at stake, where eating and killing is a matter of taste and culture, within which we cannot feign transcendence or innocence. Like Haraway, Sherwood rails against human exceptionalism by confronting our humbling realities without cynicism, creating a new form of storytelling that grasps the seriousness and humor of life, death and interdependence, or rather, a delicate “intradependence,” what Haraway calls a “becoming with-ness,” in which we are all bound together in a homogenized ecosystem.

Since culture and eating are inextricably linked, food functions as a kind of metaphor for the way nature, in its natural state, is transformed into culture, an idea associated with French anthropologist/theorist Claude Levi Strauss and his seminal book Le Cru et le Cuit (The Raw and the Cooked.) Rejecting individual self-expression as the height of creativity, Strauss saw myth-making as a collective approach to making culture. Sherwood and her animals do just this, collectively creating meaning through the interaction between her votive offering and their communal reception. The artist takes the role of mediator between nature and culture, commenting on her expeditions through a daily video diary. Throughout such documentation however, Sherwood sets out to literalize the animal, returning it from a state of human civilization’s metaphorical limits.

Accompanying the sculptural work and videos are ink and watercolor works on paper. These drawings are whimsical iterations of animal interactions with her bounty, and yet, unlike the video documentation, there is something disturbingly abject in these depictions of animals eating animals, all the more provocative because they appear as characters in a children’s picture book. Even Sherwood herself appears as a sweet-faced, meat-grinder girl in a butcher’s apron. Instead of an enchanted forest, we have instead a disenchanting sausage forest. Hyperbolic, perhaps, yet the image is only a stage removed from Sherwood’s construct of nature. The ethics of animals as consumers of our culture is fraught, yet inevitable. Many feed pets processed food from a can, whereas Sherwood gives the animal options. Sherwood discovers that when presented with a choice between natural produce and processed delicacies, the animals for the most part opt for the latter, just as humans do, but at other times they do not bite, each time presenting individualized choices and selections that the artist is happy to welcome into the piece.

Meat has come to represent human excess and agricultural unsustainability. Sherwood problematizes the boundaries between domestic and feral, as well as the boundaries between labor and nature, as she garners a nuanced relationship with animals, who in turn reinforce the absurdity and gluttony of human rituals. We can’t have our cake and eat it too, because there is no longer a division between worlds; we are all in one crippled atmosphere together. With wild animals as our companions, Sherwood argues that the human agent can begin to navigate a practical utopia within which all can inhabit.

— J. Holburn