Studio Visit: Erin O’Keefe

Interview by Matthew Leifheit, Published September 9, 2015

Erin O’Keefe is a studio artist who has taken 800 pictures of a corner in her studio since last year. It’s not that she finds the corner itself particularly beautiful, it’s just a space that—when customised with very deliberate combinations of colours and materials, lit precisely, and photographed in an exacting way—can transcend its materials and become an otherworldly experience that challenges traditional perceptions of space. This is all done in-camera, without Photoshop, by drawing on a diverse range of influences from early Renaissance figurative painting to Josef Albers to. Based in Manhattan, O’Keefe graduated from Cornell University with an undergraduate degree in printmaking and, when faced with the fiscal realities of this certificate after graduation, decided to get a masters in Architecture, and then start teaching. She did this for 23 years, and along the way picked up a husband and two daughters. Last  year, she quit her job to become a full-time art photographer, working from a small studio on the Upper West side. I saw the first pictures she ever made in a 2012 group show curated by Humble Arts Foundation that I wrote about for TIME, was immediately fascinated, and have witnessed a steady increase of her presence in both online and brick-and-mortar exhibitions in NYC and beyond. Last year, following a studio visit where Erin showed me the beginnings of her epically complex series Natural Disasters, I invited her to debut the work in VICE magazine’s 2014 photo issue, which I was putting together at the time.

year, she quit her job to become a full-time art photographer, working from a small studio on the Upper West side. I saw the first pictures she ever made in a 2012 group show curated by Humble Arts Foundation that I wrote about for TIME, was immediately fascinated, and have witnessed a steady increase of her presence in both online and brick-and-mortar exhibitions in NYC and beyond. Last year, following a studio visit where Erin showed me the beginnings of her epically complex series Natural Disasters, I invited her to debut the work in VICE magazine’s 2014 photo issue, which I was putting together at the time.

“The Disasters are ongoing,” O’Keefe told me in her studio earlier this summer. “It’s something I return to. Those were inspired by looking at images in the New York Times every day and seeing everything falling apart. There’s nothing that’s fixed. And so I wanted to build them, some of them are more chaotic than others. It’s also to do with the failure of our eyes to make sense of things. We look at this and think it’s photoshop, it can’t be real. So there’s this idea about giving up a sense of control, or something. Somehow those two ideas are connected for me in this work. There is no stasis, there is no fixed truth.”

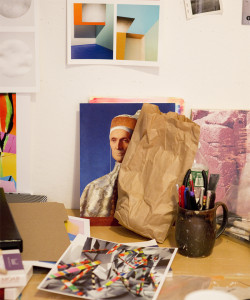

Tonight at Denny Gallery in New York, O’Keefe’s latest series, Things as They Are, will debut alongside three of the epic Disasters in a solo exhibition. Photographer Max Marshall and I went to O’Keefe’s studio earlier this summer to talk about life in the world versus work in the studio, how having kids can change your colour palette, and the inexplicable awe of perceiving something unmediated by language.

Matthew Leifheit: You have a Jan Groover postcard on your studio wall, from Janet Borden’s booth at the Armory. But the other reference images are paintings.

Erin O’Keefe: The top two are Leger, and those others might both be Gris. I look mostly at painters, I have to say.

But your background is not in painting or photography.

Architecture. That’s what I did for 23 years.

How did you come to that? Did you try being a painter first?

No, I never painted. I studied printmaking as an undergrad, and after I graduated, it was terrifying economically to think, what do you do with that. And I didn’t want to work at an ad agency or something. And I was really interested in architecture, so I got a masters degree, got licensed, and then taught.

And then you stopped teaching to be a full-time artist?

Yes, one year ago is when I formally left. Dopey economics decision but…

How does your biography impact what you’re making?

Architecture is a way of thinking about things, and particularly thinking about limitations. In any of this work, I set up some sort of rules for myself. And that’s part of the reason it’s studio-based. The world is too big. I don’t know how I’d even go about choosing what I was interested in.

Now I can make things in a much more immediate way than I could as an architect. There’s a thing that I’ve thought about where, when you’re an architect you either kind of make models or make drawings, and so you’re always referring to this other thing, but you’re never dealing directly with the thing. The thing (the building) is always at this weird remove from what you do. Photography is sort of the same thing, there’s a distance between the subject or the condition that you’re taking a photograph of, and the photograph itself. And I like that separation, that’s what I find very juicy about the whole thing.

Something to do with the transformation the camera performs in creating a new flat surface. But you’re also taking photos in the world, printing them, and then putting them back into pictures in the studio. There’s some kind of composting going on in your photographs.

Something I find frustrating is that when you make a sculpture, you make a thing, and there it is. When you make a photograph, it exists in this weird… it’s like I can give you a jpeg, and then I can give you something else, and then we can print it big. It never resolves itself into an item.

The pictures in Natural Disasters sometimes incorporate pictures of carved stone drapery on sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum. Those are pictures of the world.

Yes, but I like that that is also remote. And it’s all in the American wing, so they’re copying copying copying… There’s this weird thing where you’re looking backwards through a periscope or something. History reproduces this stuff over and over.

Are you just following your heart, or is there some consideration for adding to a specific dialogue?

It’s definitely coming from me and my concerns, but I do feel like there is this potential convergence of those concerns with what’s going on in contemporary photography. And that discussion is something I am really interested in. I have something to add because I come from this other place.

Some people are frightened if they notice things out in the world that remind them of what they’re doing.

Sounds weird and lonely. I came to this way of working through the trajectory I came to it through, and was in a position to discover all this other work that was going on that shares some of my concerns. But it doesn’t feel scary to me, it feels…

Zeitgeisty.

Eileen Quinlan is someone I was aware of a long time ago, but I didn’t totally understand what she was up to until I was on this side of photography and struggling with some of the same things.

How do you feel about formalism? Have people applied that term to your work before?

I think that my primary response to the world is like this retinal, formal response. There’s this sort of primal situation, where the work is not mediated by language. When I first saw the work of Robert Irwin—there’s this primary response of like, POOF [makes gesture of mind being blown through eyeballs]. Then you’re trying to sort if out in your head, like, what’s going on exactly. At a certain point, I do feel like the giving up to that is a very pleasurable experience. The lack of control when you can’t quite work it out. I think that’s positive. It’s like wonder, or awe. Those are big words, but the not knowing is a thing that I’m interested in.

I guess I’m wondering what you’re chipping away at. I liked what you were saying about the stone carving, which is sort of a translation anyhow.

Right, until it becomes this sort of mirrored box of who knows what’s what. Since I’m interested in space, I’m interested in creating a condition that reads one way, but isn’t that way. There is a tension there. That’s what photography can do I think, because there is this other way of translating that experience. […] The camera is taking this thing that I know is one way, and it’s flipping it. This is something I explored in sculpture as well. The way that you see is like a fly’s experience of the world, or a bunny, or my daughter whose eyesight is really terrible is like radically different than yours or mine or whoever. It’s a subjective experience. So I’m thinking about that.

Between architecture and photographs, there were sculptures?

The whole time I was an architect I was making sculptures. I started taking photographs of them, and people told me they were cool on their own. Those sculptures were very concerned with cubism, and thinking about fracturing a view. So, the concerns here are very much the same here as in the sculpture, but with the interjection of an idea about colour.

It does seem like you’re using a specific colour palette. Lots of synthetic colours, right?

Well, it’s all paint, right behind you.

But you like fluorescents.

Yeah I always kind of liked those. But then, the other day, it was like, OH MY GOD, TAUPE. (laughs) That’s what I am going to do. So, it evolves. I can’t say that anything’s really fixed.

The studio can be like a laboratory for you, or a place of potential that doesn’t necessarily require a plan in advance.

Yes, you made a comment when you came for your last studio visit that I got a lot of mileage out of a corner. Literally, since then I’ve made literally 800 photographs of corners. Can I make stuff with the stuff I find around here? Can I make things only out of things I generate with the printer, and then print them back out of the printer, so this Epson printer becomes sort of a snake that ate its tail?

How many days a week do you spend here?

4 usually.

And you have two kids?

Daughters, 14 and 18.

So you have like, a life.

Oh, yeah, there’s that whole thing.

How does your life outside of this room come into it? Does your family life or your personal life come into the pictures at all?

When I was making sculpture, colour did come into it a bit, and it was definitely because of having kids, because of having all this brightly coloured crap around. I was like oh I like Barbie, these are great pinks! And so, you’re less serious about things because you can’t take yourself very seriously when the primary people in your life don’t.

(laughs)

So there’s that. And my husband is an architect. So that part of things is always there, always looking at stuff in the world critically. And I think that’s the primary thing that we do. We go and look at work…

Do you take your kids to see art?

I used to when I could make them go. But my 14 year old is starting high school, and she is not so interested in doing things with us. But, they both went to Roden Crater, which was awesome.

It was good?

Yeah. So they’ve done some of these amazing art things that I’m not sure they appreciate yet, like, one of my daughters fell asleep there under the dining room table with James Turrell.

How did you get to do that?

My husband was working on drawings for the Crater. Terrell has collaborated on a few projects with the firm where he works.

So there is actually a connection between you and California Light and Space.

Oh, his work was like [mind blowing gesture]. And having the opportunity to see Roden Crater was, you know, that was pretty peak.

Will you ever make installations? It seems like you’re not set on making flat photos. I’m interested in where this is going… but of course you don’t know either. Do you see going back into the third dimension?

That is a frustration for me. The surface of a photograph is cool, it has that window/mirror thing. But sometimes there is something that I want that I can’t quite get at. So I would say that the sculpture will come back.

—

Erin O’Keefe’s exhibition Things as They Are opens tonight, September 9th, 2015, at Denny Gallery, 261 Broome Street NYC. It will remain on view through October 11th.

—

Interview by Matthew Leifheit / Photographs by Max Marshall / Published 9 September 2015