Meet the Artist

Drawing Without Fear: Lauren Seiden on Radically Reshaping the Work on Paper

By Dylan Kerr, May 19, 2015

For the past several years, the born-and-bred New York artist Lauren Seiden has been quietly updating one of the most fundamental artistic mediums: graphite (i.e. pencil) on paper. More akin to wall-mounted sculptures than the term “works on paper” may initially suggest, Seiden’s pieces appear at first glance to be welded out of sheets of metal or carved from blocks of marble. Upon further inspection these abstract works begin to open up, revealing creases and tears that disrupt any illusion of solidity.

Seiden’s process is highly physical, intensely time-consuming, and often very messy, which when combined with her strong work ethic means that most of her waking hours are spent in her studio. Artspace caught up with the Denny Gallery artist at her new space in Greenpoint, Brooklyn to discuss giving up “crutches” in both her work and her life, the potential pitfalls of maintaining an artistic presence online, and how making art can be an act of bravery.

When did you first start making art or realize that you wanted to be an artist?

I grew up in Manhattan, and I was always drawing and making things. Our schools would take us to museums, and as an only child I would often sit by myself drawing or playing with a watercolor kit. There are tons of pictures of me sitting with my grandpa collaging, and my mother still has all my childhood paintings framed. I transferred for part of high school to the Huntington School of Fine Arts in Long Island. I also studied studio art at Bennington, but after graduating I didn’t get a studio for about three years.

What were you up to in that period of time?

I had a few random jobs and worked at galleries for years. My last gallery job was at 303, which I left after receiving a grant and starting to show more often. In 2007, while still at the gallery, I moved into a large shared studio on the Lower East Side. At first I was really, really shy about making work—I put up a curtain and hid in the corner trying not to be seen. At that point, though, it was really important to me just to start working again. I started working day and night and on the weekends—I didn’t really want to be anyplace else.

Before that I had been feeling a little lost, and a few months into working that intensely I remember asking a friend, “If I was supposed to be an artist, wouldn’t I have needed this to truly be myself?” They replied, “Who says you’ve been yourself?” So, yeah. I quit my job and decided to not have a safety net, to just kind of go for it.

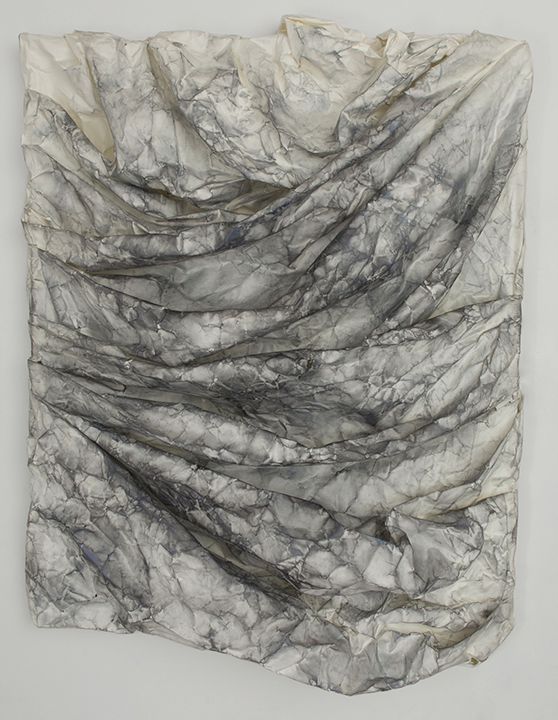

Raw Wrap 21, 2015. Graphite on paper.

That’s a big step to make. What were the early effects of that decision on your life?

It was only after I left my job that I found people in the art world who felt like peers. It sounds corny, but it was just a really inspiring community to be a part of. It was incentive to work, and I was just happier. Being not on the other side of it just made me feel freer to flop a bit, to have that time to make some failures.

Can you say more about that? What was it about working in the gallery context that made you more cautious about experimenting?

It was really just time. You’re so saturated with art, and you’re not as inclined to go to all the openings because it’s been a long day and you become sick of looking at art. Instead I would go to the studio, and I really didn’t have time to enjoy the art that was happening around me. Once I started working in the studio every single day, it was amazing how much time there was to make things that didn’t work and then destroy them or rework them. I just didn’t feel the pressure that everything had to be perfect, and therefore the work had room to develop into something beyond my initial vision for it.

That’s a good segue to another thing I’m curious about. On one hand you works are generated through a certain amount of rote process, but on the other hand you’re looking for enough space to let them become more than the results of that process, more than just what’s in your head while starting out. How do you strike a balance while you’re working?

It depends. I feel like the more I work, the less control I need.

How so? Could you tell me a bit about the specifics of your process?

With the paper works I usually have an idea in my head, but I’m not quite sure how I’ll apply the medium. I roll out paper two or three times the size of the stretcher, wet it down, and find the balance of how malleable I want it to be. I work it into a shape, then wrap it around the stretcher as you would a canvas. At this point I try to let the form find itself — I always feel that’s when the work is at its strongest. That’s when I start working the detailed folds into the paper.

Cloaked, 2015. Graphite on paper.

By “working,” do you mean physically molding the paper?

Yeah, physically moving it around—sculpting, in a sense. The larger the piece, the more physically demanding it is. Once the paper is set, I let the shape dictate where and how I’ll apply the graphite. The act of folding the paper strengthens its structure while weakening the surface, allowing for necessary manipulation of the material in order to maintain stability. It’s about finding the balance between those things, and that really opens up an element of chance. It allows the material to do its own thing and fall where it will.

The use of paper opens up the possibility of breakage and other accidents that occur within the process, leading to a choice of whether to hide it in folds, or to leave it and show the vulnerability of the material. This enhances the work by reflecting that duality of fragility and strength. Pieces with a metallic, armor-like appearance sometimes contain moments of breakage or tears, like slices through a shield after battle—and sometimes it is very much a battle with these materials. Sometimes they work, and sometimes they don’t.

When I first started making these I would either discard the piece or cover up a tear, but the more I made them, the more confident I became with the materials and perhaps the rougher I became with them. I feel that working with these tears reveals another element of what the material is, and that is important. It allows it to be what it is, not in a contrived or artificial state but in a natural way.

Do you add the graphite after the paper is shaped?

I rarely make any marks before the form is created. Sometimes it adapts or changes—maybe I’ll tear off some pieces, or re-hem or push out, but the form really dictates what the piece is going to be for me. I can’t imagine knowing how to navigate if I were to work beforehand on a flat surface.

How do you get all that graphite on there once the paper is formed?

It’s layers and layers of hand-drawn pencil. It takes a long time, but it’s methodical and kind of calming. The pieces that appear almost metallic with a heavy application of graphite are more labor intensive and physically demanding, but they’re sometimes easier than the works with less graphite because those become about decisions—figuring out where I want the graphite to go, what line I’m trying to emphasize. The restraint can be more challenging. On a good day I can see exactly where the graphite should go, where I can mimic shadows or mimic a marbleization based on the folds, tears, and shape.

Truthfully Unfolding, 2015. Graphite on paper.

Is that how you conceive of the graphite in these works, as resembling shadows or marble?

When I’m working I never think of shadows or marble per se—I’m saying that to you because that’s how others tend to describe it. I usually start with one area that I think has a clear direction, which leads me into the next section. I use my fingers to really push into the grain of the paper. Sometimes I sand it down, depending on what I think best suits my intention. After a few hours of doing this I’ll step back and see if I think it’s working. Sometimes it’s just too light and I’m ready to make a move and go bolder, so I’ll wet it down and start “painting,” moving and pushing the graphite like a stain.

I really see that effect in some of your works—it’s hard to imagine all that color coming out of a pencil.

Yeah, but it does [laughs].

Your works seem to be closely related to one another, each employing similar processes and sensibilities. How did you settle on this mode of working?

When I started making work again after college, I was painting. I kept saying to one of my studio-mates, “Eh, they’re ok, but they’re not right.” She pulled one of these paintings away and said “All right, but what do you like about it?” It turned out that it was the connection between the dark marks and the line that I responded to, so I started working with pencil and doing drawings like that. The more I did it the more I kept pulling it away and seeing what I liked in it and what I was interested in looking at, so it became more and more about the mark-making and the medium itself. The works show a connection between lines and weight, between different areas that pull at and speak with each other.

These early attempts were graphite on paper works behind frames, but I wanted them to be more tactile. I started putting them in frames without glass, then put them on top of the frames, then I decided to start wrapping the paper around the frames, and from there it started to move even more away from being behind the frame. Now the work is not on a frame at all. Part of this process is about moving away from any kind of armature or crutch—I really wanted this to be something that you could be more involved in, that you could find your way through yourself.

As a viewer, you mean?

As a viewer, but also as a maker. I’m constantly trying to find ways to push these mediums beyond what they inherently do or are supposed to be. That pushes my process, and that keeps me excited. As long as you’re interested in your own work, hopefully it will be interesting to other people. If you’re not, it probably won’t be.

Shield Wrap 10, 2014. Graphite on paper.

Working in the studio seems central to your creative process. What is your day in the studio like? What kind of environment do you like to work in?

It varies. I just moved into this space, which is twice the size of the space I had, and it took me a while to not be scared. It’s like looking at a really big blank canvas. It’s pretty clean right now, but it’s usually really dirty.

Sometimes I’ll walk in and it’s super go-time, so I move fast and my decisions are really obvious and instinctual. Other times the process is more about sitting in here and staring at the work, seeing how it looks in the context of itself and of the other pieces and letting it haunt you for a bit to figure out what it needs or if it’s done. For the most part, it’s really about not being afraid and just continuing to go. If I feel hesitant about something I try to just push past it and remember that if it doesn’t work it’s not a bad failure. I think you have to be brave every day to come in here and work, to make yourself work. The studio is never the wrong place to be.

Working within relatively strict confines in terms of materials and process, how do you keep pushing yourself and your work to new places?

I’ve been playing a bit with pigment lately. It’s really subtle, because I don’t want color to be an artifice or make-up. The graphite and paper both seem so limitless to me, but I am trying out some different materials as in my newer thread works.

What excites me about the work is that it’s made with really traditional drawing tools that are pushed beyond what their preconceptions might be. I’m trying to take it beyond a drawing or painting and just have them be objects created from these elemental materials.

You go through an intensely physical process in making these works. How do you see this mode of creating relating to the digital processes that are increasingly important to artists today?

It probably only relates insofar as it’s not part of that trend—not to say that digital art is a trend that’s going to come and go fast.

I think that art being Post-Internet or digital or even just online can be a wonderful thing—it’s great exposure, and of course it’s part of the time we live in—but I think it can be a disservice to artists in terms how you think of making the work. It creates a pressure of always having something new for this virtual audience, which to me is kind of sad. When you think about great art and artists throughout history, you think about the maturity of a career and a studio practice that grows and develops, not one idea quickly realized and deposited online followed by another new and flashy piece.

I’ve had some really odd studio visits where people don’t ask questions when they are with the work, experiencing it in real life. They just say, “Oh, it looks good in photos or on Instagram.” It’s a weird thing—you want somebody to engage and ask questions and be curious. You hope to always do that for yourself too. So when I feel that curiosity drift and get replaced with an exterior pressure, I need to stop and remember that this is happening in here, for me, from me. It’s not just online.

Fallen Ribbon, 2015. Graphite and mixed media on silk and polyester thread.

Having worked on both sides of the gallery system, what are your thoughts on the role of the gallery in our current, booming art economy?

There are two sides to it. If you’re an ethical businessperson growing with your artists, cultivating careers, encouraging and supporting them, as well as properly conveying your artists’ work to the world, then I think galleries are a wonderful platform. I think they are important because a gallery allows artists to create their work within an intended context, either a solo show in the context of the work itself or in a group show with your contemporaries as part of an ongoing conversation. I think that’s so important, and that probably happens less at art fairs than in a gallery.

So yes, I do think galleries are very valuable for that reason, but there are also different ways to construct that dialogue now—people putting up shows without a brick-and-mortar gallery space, self-promoting online and being more grassroots about it, or groups of friends joining forces and being a little movement, creating a dialogue within themselves and then making shows to work through those conversations.

What are your relationships with your collectors like? Are you close with any of them?

There are a few that I do have close relationships with. One in particular is an unbelievable supporter. The way that she speaks about the work, it really shows me new ways of seeing it. I’ve never had somebody come in and curate my studio like she did, creating a timeline to tell a better story.

She always describes herself as an “emotional collector.” The first visit I had with her was fine, and then the second visit was this crazy, intense crit. I had made these works, and she came in with a gallerist and said, “This is technically perfect, and I just don’t really care.” I like a tough, thoughtful critique, and it really made me think about the work and the importance of having life to it, of having movement and heart in it.

There was a new piece in the corner that she pointed out and asked “What’s this?” She always seems to find the first of every new series—there must be an energy or a pace to it, perhaps because you’re kind of fearless and have no expectations for it. It reminds me to have that fearless, loose energy in the work, and to not get sterile or be process-oriented to the point that it’s clinical.