Natalie Lo Lai Lai (b. 1983, Hong Kong) has a distinct practice, using video installation as a means to interact with nature. She is a member of Sangwoodgoon, a farming collective started in 2010 by activists in Hong Kong who opposed the construction of a high-speed railway which would displace villagers and farmland. Lo’s practice is at once deeply connected to Sangwoodgoon while working beyond its context, using farming to think through alternatives to repressive governance and the relationships between people and nature.

Installation view of “The Wild and the Tame”, Denny Dimin Gallery, Hong Kong

Installation view of “The Wild and the Tame”, Denny Dimin Gallery, Hong Kong

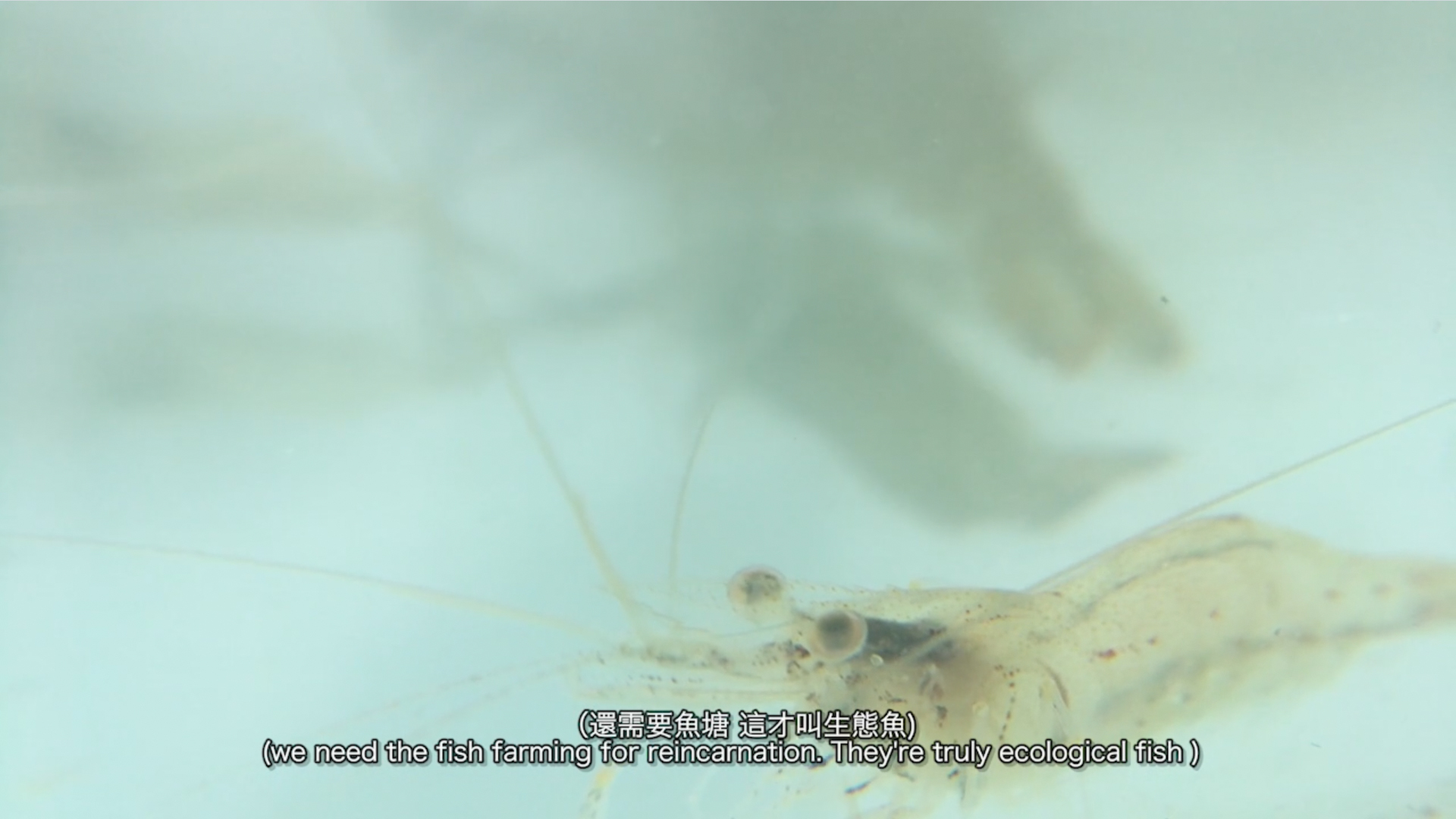

Natalie Lo Lai Lai, Voices from Nowhere (video still), 2018

Natalie Lo Lai Lai, Voices from Nowhere (video still), 2018

Voices from Nowhere (2018) is a video piece inspired by a coincidental encounter with a farmed fishpond in Yuen Long, Hong Kong. In July 2022, we were lucky enough to get a chance to visit Tai Sang Wai and Sangwoodgoon with Lo, and to speak to her about her practice, her participation in The Wild and the Tame, and reflections on Voices from Nowhere four years on.

Hayley Wu: The Wild and the Tame marks your first time showing Denny Dimin Gallery. How did you become involved in this exhibition, and what is the connection between your work and its theme?

Natalie Lo Lai Lai: The line-up to The Wild and the Tame was made by my good artist friend Ip Wai Lung, whose work has been exhibited at Denny Dimin Gallery [in New York and in Hong Kong]. He connected me with Katie Alice, who is a partner of the gallery, and Katie Alice kindly invited me to join the group show. It was my pleasure to be invited to take part in the exhibition, which offers a platform for our six artists to address human interaction with nature through our personal experience and our works.

Voices from Nowhere responds to the exhibition’s theme by illustrating how humans curate and make a living with tamed nature–fishponds. There is no judgement on the practice, and I believe visual artists are working better to arouse contemplation on ecological issues, but not propaganda. The essay film centres my thoughts and questions on the life and death of fish, the ethics–if any–of food consumption, and so on. I am also happy and surprised that the legend and myths mentioned in the film echoes Dana Sherwood’s style of magical realism, portraying contact between human and non-human animals.

HW: Let’s go back to your beginnings. You studied fine arts, but worked as a travel journalist before becoming a professional artist. Could you tell me about that trajectory, and what you took from the experience?

NLLL: When I graduated from university, I thought, “Well, I want to make art, but just being an artist is quite boring.” So I deliberately looked for non-art jobs, like in research, and it just so happened that a journalist hired me. I worked full-time for four years, until the anti-Hong Kong Express Rail Link movement started.

That period trained my ability to look at photography. My job was to write, but with the help of fellow photographers, I learnt about what made a good photograph and what was ordinary. There were also some lines of thinking and ideas that were established during that time. While I did shoot stuff during that period, they don’t particularly show up in my works.

HW: Where can you see the influences of that time in your work?

NLLL: In the way I combine footage from abroad and from Hong Kong. My early essay films involved footage from abroad from research trips while doing my MFA, or from summer school. I didn’t want to keep the ideas in my works trapped within the context of Hong Kong, because when we talk about nature, there are actually things in common across the world. I can be a bit picky with regards to these positionings. Or with my short film, Cold Fire, the text and some of its scenes came from my thoughts on flying as a travel journalist. The concrete content of my works and my ways of thinking have both been affected.

HW: You’ve previously expressed that you’re a little uncomfortable identifying with the label ‘artist-farmer’. Why do you feel this way, and how might you characterise what you do?

NLLL: I think the honest way of describing the situation is that I have a kind of hesitancy towards what people call me or what I call myself. If I am an artist farmer, when I farm, do I keep an artist’s ego while working? I don’t want that. But to call myself a farmer is not quite right, either. Still, my art is all about agriculture. The more accurate way of describing what I do is that I vacillate between these two identities of artist and farmer, so it’s hard to label, but my practice is about farming and nature.

HW: Given that your artistic practice is so intertwined with your work on the farm, what then is the relationship between these two parts of your life?

NLLL: It must be understood as complimentary, and while my work relates to farming, it is never just about farming. My work uses farming to discuss a collective’s workload, or to understand a very different perspective towards nature. If in the past you might have thought that permaculture or organic farming was unconditionally good, then the actual practice of farming makes you recognise that solely using such methods creates another set of problems. As a farmer, you become a frontline worker who faces these issues.

Perhaps something I appreciate now that I farm is that there is no one who has the moral high ground. There are many things I understand now through the lens of human nature. I see all this through farming–which is not really just about farming–and in turn this deeply influences my artist practice and perspective.

HW: Your work addresses major political events in Hong Kong such as the 2014 and 2019 protests in Hong Kong, which largely take place in the city’s urban centres. Yet you are often responding from a rural context. How do you make sense of these seemingly discontinuous locales?

NLLL: At its core, it’s a question of how we engage with a society, a city, or a rural village under different circumstances. So an early example can be found with the Choi Yuen Village (菜園村) protests, where my collective was entering from a so-called city context into a rural village, learning about the situation– and actually, it wasn’t clear at the time why we felt compelled to protect the village. It wasn’t as if we were from there. But we slowly came to understand that these explorations of autonomy helped to override the uncomfortable feelings of living within a system. Of course, you can’t escape it. You’re still physically in Hong Kong, still paying your electricity and water bills. Hong Kong is very condensed. You can travel to the city very quickly. It’s almost impossible to separate the urban from the rural. You can try, but there is so much activity and interaction between the two contexts.

With The Days before the Silent Spring, I wasn’t trying to force the connections between the urban and rural in the work. Rather, it reflected our collective’s considerations at the time: do we stay and work on the farm, or do we take to the streets? Some members wondered if we should stay with our farm because that was what we had chosen to do. This didn’t come from feelings of apathy towards society, but rather a sense that what was happening on the farm was the best contribution the collective could offer, and that we should keep going in that direction. Whereas others thought that, in such a burning moment, what the movement needed was for people to show up. And since the collective isn’t interested in turning away from the world, we will always have these thoughts and struggles.

HW: Fermentation is a recurring motif for you, and at times it seems to be a metaphor to describe the other processes in your works. Why are you interested in fermentation, and what does it offer you in terms of thinking about humans and the environment?

NLLL: There are a few ways of looking at it. Fermenting food is something that farmers already do with leftover and unsold vegetables. It is a way of preserving and adding layers of flavour to food. But when I went to investigate and learn more about the topic, I discovered that the world and interpersonal relationships can also be understood in terms of fermentation. No matter how you try to control it, it’s hard to control. This is especially the case with wild fermentation, where its many influential factors make it hard to repeat the results.

That’s why I think fermentation is particularly appropriate for the circumstances I depict, where there are many things that can’t be controlled. Works like Cold Fire, Seesaw, The Days Before Silent Spring do this. The Days Before the Silent Spring captures the fermentation of our collective’s members over a period of time, whereas Cold Fire describes a flight journey, which is really about how to expect the unexpected, or how to prepare for emergencies. It was made during the 2019 social movement in Hong Kong. The feeling it was trying to capture was that of not knowing what was going to happen. You might also describe these works as trying to depict situations in which you have to accept the reality whether you win or lose, or in which there is no such thing as winning or losing.

HW: Can you tell us a bit about Tai Sang Wai, the village where Voices from Nowhere was shot?

NLLL: An earlier generation came down from Panyu (番禺) and first settled as rice farmers–in particular red rice, since Tai Sang Wai is in brackish water. They sold some of it, kept the rest for themselves, and after a period of time they began to build their own fish ponds. Then there was a land development project called Fairview Park (錦綉花園) in the original village. Luckily, the area was seen to have preservation value, so the developers couldn’t develop it all. The 1980s was also a time of less aggressive levels of land development, as at the time the British Hong Kong government had no interest in linking their infrastructure with Mainland China.

What is special about Tai Sang Wai is that you can see the world of the fishermen and the farmers, and how the preservation value of its natural environment protected the villagers from eviction until Fairview Park. And I’ve said recently, people are now “in relationship with air-conditioning”, and so there are always also ways in which we are disturbing the environment. Tai Sang Wai is an ideal case for describing all these kinds of relationships. Of course, its natural environment is also beautiful.

HW: Voices from Nowhere is a follow-up work to Voices from Elsewhere, a film made for the 2018 Sustainable Festival. How did this festival come about, and how did it ultimately result in Voices from Elsewhere?

NLLL: The festival started around 2017, when Art Together and the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society decided to host it together. The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society had a member called Christina who had been working on nature education. She felt that one of the poor practices surrounding nature education in Hong Kong was that educators typically just asked students to collect data, which didn’t really create a connection with nature.

As someone who enjoyed land art, Christina sought out Clara from Art Together, and proposed that they organise an event together about exploring nature in Hong Kong. There was an existing relationship between Tai Sang Wai and the Bird Watching Society, so of course they wanted to promote the fish farms.

The project recruited a few artists, myself amongst them. At the time I knew I was going to film a video work, but I didn’t want to just accept the viewpoint in which the fish farms were presented as unconditionally good. After getting to know the villagers for a while they started to tell me stories from their decades in the village, and I wanted to put these stories into my work to offer some context to the site.

With Voices from Elsewhere, it felt like no matter what I was shot I couldn’t get what I needed, and it was only in the last week that it exploded into its final form. After the festival, the Bird Watching Society allowed me to join their workshops and the villagers were kind enough to keep chatting, so Voices from Nowhere thus had more time to develop. What resulted is a work which thinks about life and death through the perspective of the fish, or about people in relation to fish.

HW: One thing I noticed about Voices from Nowhere is that its subjects seem quite un-self conscious. How did you create this effect?

NLLL: I think the feeling of “naturalness” came from my original intention to avoid directly shooting people, as in a documentary. So when conducting interviews or listening to stories from the villagers of Tai Sang Wai, I would only ever record the sound. So after we were acquainted for a while the villagers became more natural on-screen, and I think the camera angle I shot at also had an impact. The first shot of Voices from Nowhere, where a villager is pulling up the net, was just shot with a GoPro. Even though she knew she was being filmed, there wasn’t any particular pressure on her to act.

Perhaps it’s because when filming on my farm or for other works, I find it hard to avoid making people aware of the fact that they are being shot. I don’t want to seem like I’m attacking or unintentionally violating my subjects. I’ll often use more ‘relaxed’ angles to film, or use a phone, which can be easier, or shoot using lower angles where I can film people working in a more natural way. This is related to what I am filming, and the relationships I have with my subjects. I can’t film talking heads, because I find even such a simple act to be really insincere. It makes me really uncomfortable.

HW: Voices from Nowhere is an essay film, a genre you often use for your works. Why do you prefer this genre?

NLLL: I haven’t edited films for a long time; it was only from 2015, 2016 that I started making more video works. Around that time, a friend pointed out that aside from creating video installations, the way a video was cut and edited was also crucial. If a video work is good independently, it offers something different in terms of articulating a filmmaker’s thoughts. So my first video work was Glacier, and as I hadn’t had much experience with video works, it meant that I could try many things from there.

Even with simple elements such as text, visual and audio, I find there are many ways of combining them and experimenting with them. So with Voices from Nowhere, why did I stay in the village after the festival to continue learning about the fish farm? That was because for the festival, I tried to make a work that was easier to understand That became Voices from Elsewhere, which resembles a mockumentary. But I also wanted to try to make a work that centred the fish, and focused more on internal thought processes. That’s how Voices from Nowhere came to be.

One of the reasons Voices from Nowhere needs to be in conversation with Voices from Elsewhere is that aside from differences in context, they use some of the same footage. I was experimenting with how to use the same material, but to narrate a different story through text or script, and to create a completely different tone or vibe. I quite like to try these kinds of things.

HW: It’s been four years since you made Voices from Nowhere. Given that exhibiting this work again at Denny Dimin Gallery gives you a chance to reflect on the work, have there been any developments on the ideas you were trying to express then?

NLLL: For Voices from Nowhere, which was about in-depth internal thoughts, I came to feel that people are an overriding force. There is a question of rights with regards to fish farming, but the fish and plants are also working hard to survive. They’re following the course of nature, and have to face the consequences of the changing weather or risk dying out. Their lives feel a bit more timeless; they are not so concerned with questions of development. Of course, they may get wiped out by the conditions around them, but it seems that there is something more universal about their existence.

Of course, fish farmers and fishing in Hong Kong is increasingly rare, and a lot of people wonder if it is ethical. But sometimes I wonder if fish farming provides an alternative to enjoying fish? How do people arrive at these ethical positions; how does a farmer decide to grow vegetables? Why don’t we just live nomadically, picking vegetables from wild growth? Fish farming isn’t particularly bad, but it seems to be deeply affected by the changing environment. So it seems to be disappearing, and while it’s not like it can’t be protected, the practice may not be able to survive in this particular place. I’m not so pessimistic to say that the practice must be lost or will definitely disappear. I just think its only option is to find another way to survive.

In the case of Tai Sang Wai, at the time of filming Voices from Elsewhere and Voices from Elsewhere we wondered if it was a special case. As it stands, the village as it stands is a replacement site for the original village, so supposedly it wouldn’t be demolished. But that’s just what was discussed, and if those in power want to demolish the village then they can. It seems like we cannot avoid these suburban developments, and the feeling is that it’s just a matter of when it is your turn. This issue is one of the reasons I started farming, but it has also created an opportunity for others to understand the situation.

What I mean to say with Voices from Nowhere is that from a modest starting point, such as understanding a fish, its internal world, and thoughts on survival, you can thus develop a multifaceted perspective towards how its ecological conditions can and do change. What I see now is a kind of stimulation for my work, as the fish of Tai Sang Wai face another challenge. The work is actually unfinished. What is tragic is that its world has to be so unstable.

Natalie Lo Lai Lai, Voices from Nowhere (video still), 2018

Natalie Lo Lai Lai, Voices from Nowhere (video still), 2018

Installation view of “The Wild and the Tame”, Denny Dimin Gallery, Hong Kong

Installation view of “The Wild and the Tame”, Denny Dimin Gallery, Hong Kong

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This interview is courtesy of the Hong Kong Art Gallery Association.