BLACK PHENOMENA: On Afropessimism & Camp

by Hafizah Geter

“Me, we,” Steph says, quoting Muhammad Ali. She points her finger from me to her, turning the history that daisy-chains us into shorthand. We gaze out from Prospect Park’s highest pinnacle. Like the frogs chameleoning in the pond two hundred feet below us, our sentences leap from one conversation to another—art, ancestors, this Hunger Games called America. Gulps of white clouds hover at our waist level, pressed like pennies between a gentrifying Brooklyn and a sky painted turquoise by morning. Wanting to map how the we knows what the we knows, I’m tempted to compare our memories.

Steph and I have been friends ever since I met her through my wife years ago. Where my father is a painter and visual artist, Steph is an art curator. In different ways, Steph and I have both spent our lives deliberately steeped in Black images, Black possibility, and Black art. Like me, Steph spent her childhood years in a Black Baptist church, and her last name, Baptist, is pronounced like the religion. Steph grew up in New Jersey. Me, in Ohio until my parents moved us to South Carolina when I was fifteen for my father’s new job teaching art at an HBCU. But there is something about Black church that turns all Blackness a little Southern—proximity to the plantation, I think.

In her 1934 essay “The Characteristics of Negro Expression,” Zora Neale Hurston—the folklorist, anthropologist, author of Their Eyes Were Watching God, and the daughter of a carpenter and Baptist preacher—writes, “Whatever the Negro does of his own volition he embellishes. His religious service is for the greater part excellent prose poetry. Both prayers and sermons are tooled and polished until they are true works of art. The supplication is forgotten in the frenzy of creation.” In my remembering, it’s always the women who catch the fever. It’s the women who speak in tongues. Always the big-hatted women sprinting in place with the quickness of sons. Everyone in grandma’s church knew who we were running after: the Lord Our Savior, the Mr. Holy Ghost. We knew America could send you on like that.

~

Along the path below us, the trees touch their heads together in preparation for the afternoon’s heat. Their beauty so extravagant it teeters on cartoonish. Between me and Steph was a world where George Floyd had been dead a little over a year. Black people had spent the previous summer protesting through a deadly pandemic. We’d traded HANDS UP, DON’T SHOOT for FUCK THESE RACIST ASS POLICE! If we could have no justice, no way in hell would America have any peace.

“If I’m centering humanity, in particular Black humanity, we’re going to be okay,” Steph says. We’re talking white destruction, Black hope, and the aesthetics of Camp. It’s a discussion I began last fall with another friend who’s a literary critic. Three seasons later, Camp’s still on my mind. Also rigorous with her looking, I’m hoping Steph can help.

A style and sensibility lifted from Black culture, Camp entered the mainstream conversation in 1964 via “Notes on Camp,” Susan Sontag’s fifty-eight-point essay on the qualities of Camp. In that portrayal, Camp is commonly seen as the love of irony and artifice, a theatrical devotion to what the mainstream considers ugly and/or garish and gaudy. But in its original and Blackest manifestation, Camp is a way of looking, one that shifts whose gaze has power as well as who can be at the center of the political project we call beauty.

Steph is the founder of Medium Tings, a gallery and project space originally housed at the top of a Brooklyn brownstone where she lived. She later expanded Medium Tings to include public art and collaborations with other galleries. It opened in 2017 with a solo show for Jonathan Gardenhire, a Black photographer who also performed live music with Kita P. I walked through the doors, and it was like walking into a church after the sermon. The congregation a little full, a little drunk on the pastor’s proselytizing cadence. If it was summer, summer testified all over our faces. We wore the perspiration of the world and the heat of being witnessed upon, like both Steph and I wear now at the flattest peak of the park, overtaken by weeds-turned-trees and fresh air steeped in pollution.

In the gallery, Gardenhire and Kita P sat on the floor. Behind them, the fireplace was gold with a cream trim and above it leaned an oval portrait of Frederick Douglass by the British Nigerian artist Mary Evans. Black folks nestled in corners of the gallery’s two main rooms. We held our shoes in our hands. We occupied all sections of the couch. We sat on the floor leaning against it. From our hair to our clothes to the jewelry adorning our bodies, style unfolded like we were inside of a Black family photo album being made in real time. The space was louder and Blacker than any white gallery in Manhattan would’ve allowed. Here, we could let our shine out without the worry of cops being called. I thought of my childhood hanging out in Hikima Creations, the Black art gallery my parents owned when we lived in Akron, Ohio. I thought of all things Black church.

Natural light and softness drenched Gardenhire’s portraiture of Black men’s faces, eradicating the distance between the subject and viewer. In one photograph, Shomari, a topless Black man gazes over his left shoulder at the camera as though I’d said his name. If I’d reached out to touch the photograph, I would’ve touched skin. Shomari was calling me in. Behind him, the backdrop was a shock of bubblegum pink. A few portraits were intentionally out of focus. Still, all that was queer spoke.

Medium Tings, this gallery born from a Black woman’s home, reminded me of the Kwanzaa events my sister and I attended as children, that confluence of Black art, Black music, and the way we combined Black American and African traditions into a single expression on our bodies. With the exception of my African mother, all the adults in those Kwanzaa rooms of the ’90s seemed to be the Great Migration’s Southern runaways. Its daughters, or, like my father, its sons. Each expression, each person, a necessary ingredient to the collective getting free.

~

“Blackness is social death,” I say to Steph. Around us, red robins, blue jays, warblers, and starlings—the whole animal cast of a Disney film—appears. Foliage pops from every untarred patch of earth. Chipmunks dash in and out, racing our feet. I’d been carrying that Frank B. Wilderson III quote with me for over a year, worrying it smooth in my pocket. Steph nods, looking into the wind—her confirmation releasing something in me. We are Black women. Every day, we experience a white America that imbibes this death sentiment. America—to use police code—receives us as N.H.I.: “no humans involved.”

In his book Afropessimism, Wilderson asks if the world as we know it requires Black death to understand itself. He describes Blackness as having the same borders of slaveness. Wilderson argues that the spectacle of Black death releases the pressure valve of the world. He believes what we suffer today as Black people, we’ll suffer tomorrow, but worse. He also says the most miraculous thing: “social death can be destroyed.” We can “burn the ship or the plantation, in its past and present incarnations, from the inside out.” But first, he says, we must assume the position—Lord, let me accept the things I cannot change. Though, Wilderson warns, the end of our “non-human” status would trigger an apocalypse.

Black folks who’d lived, over and over, through the end of times warned of white people: everyone of ’em got the devil in ’em. We were cautioned white folks couldn’t be trusted, warned: they refused to be fixed. Every day America wanted to kill us, and our parents, our grandmas, our neighbors, our aunties and uncles knew all the ways our country could punish us for mistaking what we had for what white people called freedom. Hell if they were going to watch us help America along. We’d already been buried alive. They meant, how dare you choose baptism by fire, after all we’ve done to get you to water. Having arrived, we were forbidden to drown.

I want to know, until the burning comes, if we assume the position, what do we do with it?

—What if one way through was Camp?

Black people have excelled at Camp ever since enslaved people invented it through the cakewalk—America’s first national dance—and long after white culture and the 2019 MET Gala theme erased us from it. From our music to our dance to our language to our gestures, to the way we season our food, to our fashion, to our religion, to our bodies themselves, Black people are perpetually in the process of making and remaking American culture. Our Camp includes Josephine Baker’s banana skirt performances, Blaxploitation films, voguing, and Carnival. We’ve got Camp luminaries like Grace Jones, Erykah Badu, Bootsy Collins, Lil’ Kim, Missy Elliot, Busta Rhymes, André 3000, and Lorraine O’Grady’s “Art Is…” movement. Our Campiest Camp of all is the excess of a Black congregation’s Sunday best—the zoot suits, the bright colors, the big hats.

Thirty years before Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” began to dominate the historical Camp record, there was Hurston’s foundational Camp text. In “The Characteristics of Negro Expression,” Hurston presents a framework for how Black people respond to and engage with the world around us, while also demonstrating the way our expression actively shapes the very culture that, outside of its carceral imaginings, pretends we aren’t here. Hurston writes, “While he lives and moves in the midst of a white civilization, everything that he touches is reinterpreted for his own use. He has modified the language, mode of food preparation, practice of medicine, and most certainly the religion of his new country… ” Spending far too many of our living hours in domestic service uniforms planted in us what Hurston calls, a “will to adorn.” For example, in the average home of a 1930s Negro, “one always finds a glut of gaudy calendars, wall pockets, and advertising lithographs.” We desired beauty. On this fact, we hadn’t changed.

In Sunday school classrooms, in church offices, above plastic covered couches, we hung velvet Jesuses.“5. …For Camp art is often decorative art, emphasizing texture, sensuous surface and style.”; “26. Camp is art that proposes itself seriously, but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it’s ‘too much.’”; “54. …there exists, indeed, a good taste in bad taste.” Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp.” In our pews, there were fewer virgins and more homosexuals than any deacon, parent, or pastor wanted to say.“53. …homosexuals have been its vanguard.” Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp.” History haunted our old folks’ bodies. By way of respectability, church was a lesson in how sexuality could be exaggerated through the suppression of it.

My Nigerian and Muslim mother and my Alabama-born father—donning his African shirts—were always pointing toward the quotation marks.“10. Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but a ‘woman.’” Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp.” Although, as Black people we’d been born outside of them, my parents raised my sister and I to know which ones we were cast in: “freedom,” “justice,” “citizen,” “United States of America.” It was what Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” called, “Being-as-Playing-a-Role,” though, we called it “double-consciousness.”

Camp is a system, sensibility, and social practice that confronts the lie of dominant culture. It is the art of allusion, a mode of critical thinking and analysis made by a people willing to write themselves into the joke to highlight the hypocrisies within the status quo. Camp feeds off the absurdities. Like signifyin’ (the Black art of wordplay and verbal in/misdirection), like Black people throwing shade across a white room, Camp requires someone to receive the message, someone to know. Camp insists on a primary condition: community.

Elders spoke as though trying to show us that, in far too many ways, we were still trapped in the hold of the slave ship. Still stuck picking another man’s cotton. Their whole lives they’d had a front seat to history, and it had made them Afropessimists through and through. White America’s lies could fill every forest. Our elders felled us a clearing. We were people of two worlds. The second world was whiteness. The first one was us. Black adults pointed toward the future, expecting nothing less than futurity from us too.

~

“It’s almost biblical,” Steph says, laughing. Around us, the world smells fresh. The trees are so numerous, it vibrates my vision. Despite the police dotting the park loop’s perimeter, something in me sings—the woods wanting us, like an Elizabeth Catlett linocut.

We’re talking about Black family albums and how Black people keep them oversized, preserving our relatives behind hard plastic thick as our grandmas’ couch covers. The albums are a lesson, reminding us that it was once illegal to claim each other, illegal to give ourselves our own names, or control our own images. Mainstream culture mostly showcased us in mug shots and images of hip-hop culture, but Steph and I first saw our reflections through the art and photography of family albums. When my mother was alive, my father photographed us thousands of times as models for his paintings and children’s books. Beneath his paintbrush, we saw Blackness was multivalent—the truth of it was up to us. Through images of our families, Steph and I were taught how much there was inside of Blackness for us to excavate. We learned the art of looking, the possibility of being recast. And though America would deny it, History unfolded in our pictures too. We were shown how America would attempt to write us out of everything: our families, history books, our theories, even Camp—Sontag never mentions us. When writers do include Black people in their discussions of Camp, we are relegated to analogy. They say, Camp is to queerness what Soul is to us. But those family albums, which always turned into sermons and lessons, were American history with us written back in—America was pictureless without us.

History was told through the lean-to bodies of old folks. We learned the story that style could tell across decades. We learned the art of seeing and the art of being held in someone else’s sight. We learned that if we wanted a true narrative of America, it would come from us, not from them. In our albums, we lined up after church, graduations, cookouts, funerals, and double shifts, all while America called us lazy, deadbeat fathers, violent addicts, super predators, welfare queens. We learned all the rules we had to follow to survive the white world. There was, “the talk”—that brimstone and fire sermon told in a never-ending series. Unknowing Afropessimists, our parents and grandparents taught us the art of refusal by pulling the most soul-saving rule from their trick pockets: pay them white folks no mind. Lord, they could laugh.

As a child, I witnessed Black adults laugh after the spirit left them and while waiting for the spirit to come. They laughed so deep, it sometimes arrived from behind the sucking of their teeth. They laughed in disgust through the worst parts of the histories they had to tell us, laughed so hard it stunk. They laughed with their backs exhausted from working, while combing through our tender-headed scalps. They laughed after funerals, babies, cornbread, after checking their sugars. All the while, they laughed while still teaching us how to love all that our country treated as “unnatural”: us.“The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural.” Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp.” And then they laughed like we were their perfume.

~

“I don’t mean that Blackness is Camp,” I tell Steph. Two hundred feet below us, water plays against rocks. Trees lie, collapsed over the park’s streams. White swans mother their fuzzy gray ducklings. I’ve memorized the park’s hidden waterfalls. I know the trees with so much shade, that even after a rainstorm their trunks remain dry, confirmation that nature is one way to attend to the wounds inflicted by a country. I’m thinking of the cakewalk, the signifyin’, and Pamela Council’s art installations of fountains—pastel colored fondue, concrete, and mechanical—that pour with red drink, grape drink, the plastic pony beads of Black-girl-childhood, and that Luster’s Pink Lotion that I still have a decade-old bottle of under my bathroom sink. I’m thinking of Kara Walker’s sexually explicit caricature silhouettes of the Civil War South and how white people salivated in response and how some Black folks accused Walker of needing help. Of needing Jesus. I had to laugh at the spectacle that was happening on both sides—the one Walker intentionally made of herself, the one she intentionally made of us. Council and Walker took a history and shined back something I’d never witnessed before. Suddenly, the road of Black possibility forked into many, like it had a thousand times before. I’m talking to myself, talking to Steph, talking through why this sensibility fills me with hope. “But I do think Camp is one of our people’s oldest forms of expression.”

Steph says the lines between what inspires us are thin. “It could be anger. It could be love.”

“It’s why we’re the most dynamic people in the world,” I smile back. I’m meaning the way we are the spotlight on America’s contradictions, how we’ve learned to dance on a tightrope,“16. …the Camp sensibility is one that is alive to a double sense in which some things can be taken.” Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp.” and the way we make each other laugh. At the foot of every tree, insects and chipmunks turn fallen leaves and trunk carcasses to mulch.

“We wouldn’t be able to create and innovate otherwise,” she says, layering another Black fact over our ancestors’ echoes. “We had to gain new tools and new resources to be able to deal with this world. Generationally, we’re looking at it from both sides of the coin. And if we’re talking about the cakewalk … ” Steph punctuates the end of her sentence with the sermon sound of a Black “Well.” It conjures up the ancestors between us. Now, they’re here.

The cakewalk, the OG of Camp, was a dance of protest invented by our ancestors who’d been renamed slaves. In the cakewalk, Black dancers puffed out their chests, held their heads comically erect on their spines. They marched in exaggerated high-knee steps while draping themselves in an air of propriety that reached toward hysterics—all of it mocking their white captors. Cakewalking required an attitude of exuberant pride. In any other scenario, pride would have gotten an enslaved person tortured or killed for behaving above their station. But Black people performed the cakewalk at the behest of their white enslavers who, unable to follow the speed of a Black joke, got a kick out of what they misinterpreted as Black aspirations toward whiteness.

“Mimicry is an art in itself,” writes Hurston. “The art of mimicry is better developed in the Negro than in other racial groups. He does it as the mockingbird does it, for the love of it, and not because he wishes to be like the one imitated.” Our mimicry was a remaking of the culture that caged us—the Camp of it, our reanimation. We’d been kidnapped to America carrying only our souls and our bodies. With every scrap we could filch, we made something new—collard greens, hammocks, a cakewalk. With a shift of cadence, we remixed sermons like songs. Our Camp was reimagination. It demanded personality to pull off. And, as Hurston points out, personality, we Negroes have in spades.

Cakewalking was one way to carve out, in public, the private space chattel slavery denied. There is the farce of having to perform one’s humanity over and over for a group of people who’ve lost sight of their own. There are the hypocrisies buried in the absurdities—a mess so thick, I could shovel it. It’s all the ingredients for Camp. Ever since we were kidnapped here, we’ve been mapping our way through our social deaths.

By the 1890s, with Black people technically “free” from bondage, and with America’s racial anxieties soaring, white people began cakewalking, both in and out of Blackface. At the 1908 International Conference of Dancing Masters, a World’s Fair–like event in Berlin, the cakewalk was chosen to be the dance of America. What enslaved people started on plantations as a joke had become America’s official and first national dance. It’s impossible to deny the depth and genius of our Camp.

“We had no choice but to be expansive—innovative,” Steph says. “We took all of the meager meanings written on us and created our own narratives.” She is speaking of the energy we carry through our generations, and drilling into the miracle we call Blackness.

Black people are always disrupting the notion of what anger can look like. Which, I tell Steph is what I love best about the way we Camp. “Assume the position,” Wilderson says.

Okay.

Blame the ancestors, but I find a jumping-off point, a kind of hope in Afropessimism. In Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, her book about the afterlives of slavery, she defines wake work as “a mode of inhabiting and rupturing this episteme with our known lived and un/imaginable lives.” She means all is not lost. I know that America treats Blackness as social death, but like Black people before me, I can also rupture that timeline. Camp is a wake work, and like all wake work, it is part of our radical imaginings. Cakewalking is just one example of the way Black people have used Camp as a way through. In the way we Camp, I see the ashes from which we rise.

Where Camp is a relationship dependent on signaling, in a shared language, to a specific community, Afropessimism is the gulf between Black and white. Maybe that’s why Afropessimism has always struck me as being less about us, more about them. After all, from capitalism to our climate emergency, it’s whiteness, not us, that keeps birthing death.

A Sontag lover, I’m always curious about the way she forgets I’m standing next to her in History’s room. Sontag writes that Camp “is the love of the exaggerated.” Isn’t exaggeration how Black folks are marked? That marking, a way for white America to police our visibility, the same people who they mean to disappear. Camp is the celebration of “low culture” by us—a people who, as far as white supremacy is concerned, are low culture too. Hurston again: “nothing is too old or too new, domestic or foreign, high or low, for [our] use.”

Like me, when Steph looks at the absurdly white canons of art, she thinks, How can this be real? We are Camp’s origin story, not its footnote. Still, these bleached canons endure as though Hurston hadn’t whupped “Notes on Camp” by thirty years.

What white America calls “exaggeration,” Kiese Laymon calls, “Black abundance.” As a child, it looked more like a spilling. A single Sunday service with multiple baptisms, grown folks overwhelmed at finding their way. It was the permission to spill over in a world where even our breathing is considered too much. That spilling was the “Me, we”—the private made public. It’s why enslaved Black people’s cakewalking is the most brilliant piece of art.

“Our Camp is a temporary monument in a world that denies us permanent space,” Steph says. We are masters of Camp because to exaggerate the truth, you have to be able to hold onto it. Black people can walk around in white America’s lies without getting lost. “That’s the gift that we have,” she returns her wrist to that me-we gesture. Camp moves the baseline because it constantly calls the center into question. By refusing to take the lie seriously, Camp allows us to move toward something new. It ruptures respectability and all that’s expected of us in the wake of enslavement, lynchings, America gunning us down. Our Camp, like our humanity—the cup that overfloweth—spills everywhere now.

Summer 2020, cops were killing us so fast no algorithm could keep up. I couldn’t log onto Twitter without running into bodycam videos and bystander footage of one of us being suffocated or gunned down by cops or vigilantes. White allies plastered playgrounds with the names and the headshots of Black people murdered by the police. The New York Times made a fucked-up video game–esque reenactment of Breonna Taylor’s death. But Black folks, knowing that in a country like America, our monuments needed to stay on the move, made monuments of ourselves.

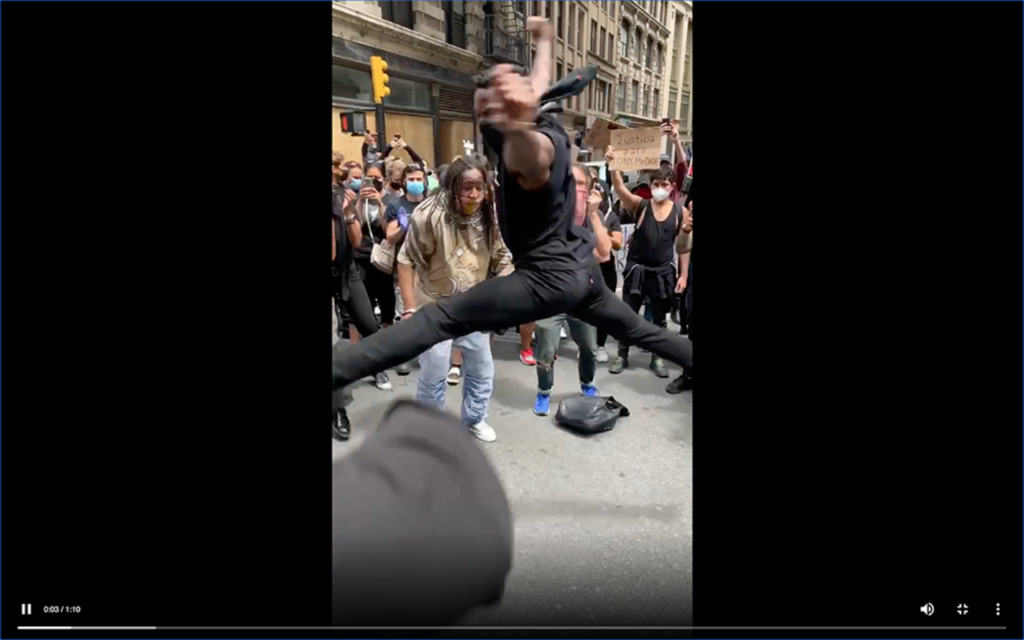

In Detroit, we marched to Black-made techno beats—a reminder to the rest of the country, we were the origin of American techno, too. In Philly, we protested voter suppression while twerking to E.U.’s funky 1988 hit, “Da Butt.” We marched our grief out in public while vibing to T-Pain’s “Buy U a Drank.” In Newark, we cupid shuffled. In Atlanta, we did the electric slide like we were at a family reunion. In St. Petersburg, we wobble-wobbled. In West Hollywood, Black queens vogued. In cities and towns across the country, we grapevined. We cha-cha’d. We krumped. We proved a social death is always in motion.

~

“I’m not interested in narratives that deplete us. At all,” Steph says. “Blackness is about making opportunities.” We both come from people who believe Blackness to be a spiritual plane. We laugh talking about how so much of what we FUBU—God, church hats, rappers, zoot suits, the movie B*A*P*S, Prince, Barkley L. Hendricks, Oprah in the ’90s and her early ’00s years, Robin Thede’s A Black Lady Sketch Show, and the FUBU clothing line itself—ends up a little Campy. This delight we take in making something for each other, for ourselves.

Around us, I note the way sweet birch, star magnolia, elm, oak, and cherry trees wave, their branches like church hands, reaching for the sky. What does it mean that four hundred years of enslavement didn’t destroy us? And how do you make sense of a people who can dance on fire? Black survival terrifies white America. Leaning into the absurd is one way we insist on reality. Camp questions the conditions. It is the performance that keeps the lie visible in the room, and this is why—in addition to being masters of living inside contradictions—Black people are so good at Camp.

“It all ties to the exploitative nature of how Blackness and death are treated as synonymous,” Steph says. We talk about the quickness with which a dead Black person becomes public property. I tell her that the eighteen-year-old Black girl who filmed George Floyd’s murder won a Pulitzer. Steph tells me that a statue of Floyd by the white artist Chris Carnabuci was unveiled in Brooklyn on America’s first official Juneteenth national holiday. Within days, a hate group defaced the cream-colored statue, literally Blackfacing it with black spray paint.

“It’s like white America is saying: I just want to take a little bit of your air every day,” Steph says. We exchange side-eye looks full of meaning. “What we’re up against is an entire world that was formulated on something that can never be erased. That narrative is always going to be a part of us, but the question is how do we liberate ourselves enough to create?”

When it comes to enslavement and the violences littered in our history, we’re expected to be sad, somber, silent, or strong Negroes about it all. But Camp is a negotiation of horror, grief, and the absurd—it requires allowing yourself the space to look at what else gazing into that abyss calls up in you.

“This is why I find Kara Walker and Pamela Council’s work full of so much possibility, so much hope,” I tell her. It is abundantly clear Walker and Council have both done their research to understand and grapple with our histories. So much has happened, there’s so much to unpack. What more liberating place to create from than the absurdities?

All over the park, the trees spill with every shade of green: chartreuse, juniper, basil, crocodile, lime, pear, and pickle. “I can only imagine how hard that work must have been for Walker to birth out of herself,” Steph says, “you have to spend an incredible number of hours going through archives and footage and seeing the most horrific things. That in itself is another level of carrying trauma.” But Steph and I both know that’s the work. To get to a place where you can be liberated into something else.

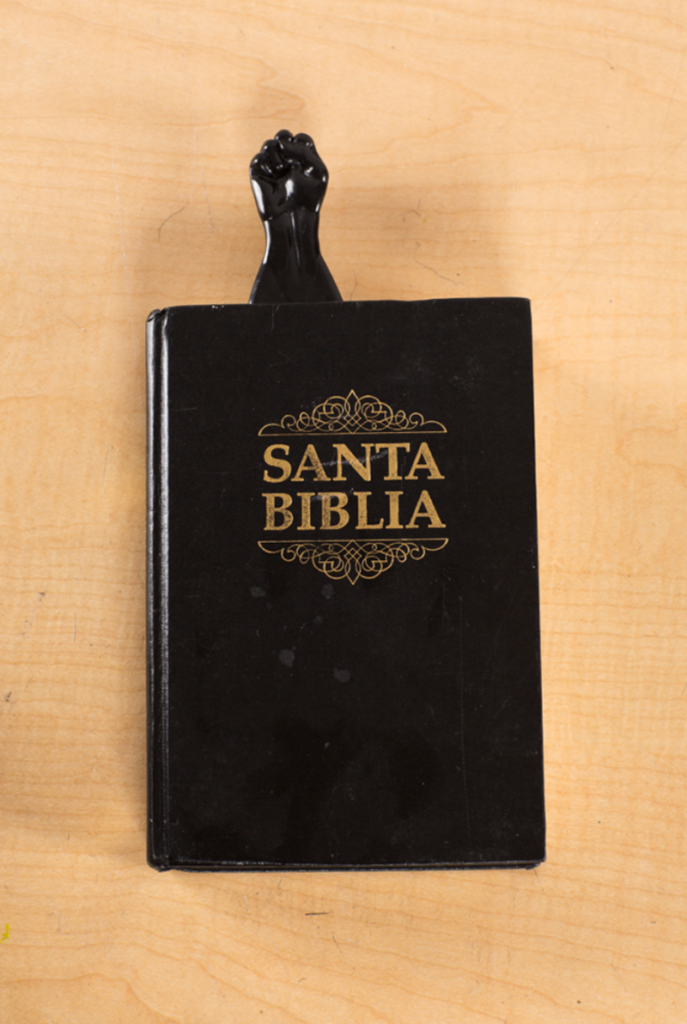

Raven Jackson, Untitled, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Still of Karma Munez (Gorgeous Mother Karma Gucci) dancing in Untitled, 2020, digital video, at a Black Lives Matter protest in Chicago. Courtesy of Karma Munez.

Hauwa Tini Geter, African Ken, 1994. Courtesy of Hafizah Geter.

Can institutions—can a country—change? Steph and I both have day jobs in white America but were raised inside the power of repurposing. Steph’s father was an entrepreneur, and she learned, if we build it, our people will come. All the money my father made teaching at the University of Akron we repurposed into Black art and our Black art gallery, where my mother also sold Black Kens and Black Barbies she’d redressed in tiny African outfits that she designed and sewed herself. I learned, if we build it, our people will come. We learned the way repurposing could ignite a rupture in what America claimed our narratives were supposed to be.

My mind jumps to the longest selling, most recognizable piece of Black art, the famous Gilbert Young painting, He Ain’t Heavy. With over a million prints sold. A Black man whose face we can’t see—only the crown of his head—reaches down from over a wall—it could be from heaven—to where another man’s hand stretches, waiting to be pulled up from the edge of the canvas, from where, we can’t see, though my guess, it’s America. Camp is like that, pulling up history to get us somewhere new. “He Ain’t Heavy.” He’s my brother.

We can’t teach white America to value us, but we can build our own galleries and tell our own stories. It’s the art of refusal and refusal is something Camp embodies.

~

We snake the perimeter of Prospect Park’s pond. People fish in pairs. The old Black men have already begun to take up their usual posts in their usual folding chairs. A white woman in a black T-shirt passes us by with an “I ain’t sorry,” written on the front and a “Boy, bye,” scrawled on the back, and Steph shoots me a barely-there look that doubles me over.

“Creating the stories we need to read and the art we need to see means we are actually starting from a place of abundance.” Steph’s words ignite something in the wind. Our abundance inverts and ruptures the dominant narratives.

Like the people who raised us, and the people who raised them, what Steph and I know of America means we are Afropessimists at heart, but we also know we can’t afford to operate from a place of death. As Wilderson himself noted at a lecture for San Diego State University, “You can’t organize Black political activity through an Afropessimist discourse. … Black people need relief.”

It’s not that Steph and I believe the world can’t be course-corrected, we just don’t know that those at the helm are willing to do it. For white America and its institutions, change would require an internal apocalypse. Are white people willing to join us on that “other side?”

“We’re not the fringe,” Steph says smiling, knowing that the origin of America is rooted in absurdity, and that white freedom rests in that absurdity. “We make our own centers. That keeps us going, because there isn’t just one center for us.”

“That center is the we,” I say, and Steph nods back like we’re sitting next to our grandmas in the pews of a Baptist church, the two of us having found our way into that Black art of call-and-response.

In the pond in front of us, turtles gather on rocks, their necks audaciously pushed out to collect the morning sun. All that’s been said volleys back and forth next to all Steph and I don’t have to say out loud—that private code, that gospel between us that is our birthright, our history.“Camp is esoteric—something of a private code.” Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp.” It takes up all the silences, save the birds.

“We must be builders,” Steph says. “Even if my parents didn’t tell me exactly what, I was raised to manifest something. Raised to know that we’re contributing to a future none of us can see yet.”

If Afropessimism is social death, then Black people must be immortal somehow. Maybe, all this is life after death, and Camp is just one of the many ways we make our way through it. After all, doesn’t Camp rupture notions of endings? Yes, Camp starts something new.

How funny, to make a list out of a sensibility.