Sean Fader’s practice celebrates and interrogates digital technology

Written by Marigold Warner

Published on July 14, 2020

In his latest exhibition, Fader presents Best Lives — portraits made by and for the queer community — alongside a powerful digital installation that maps LGBTQ hate crimes in America

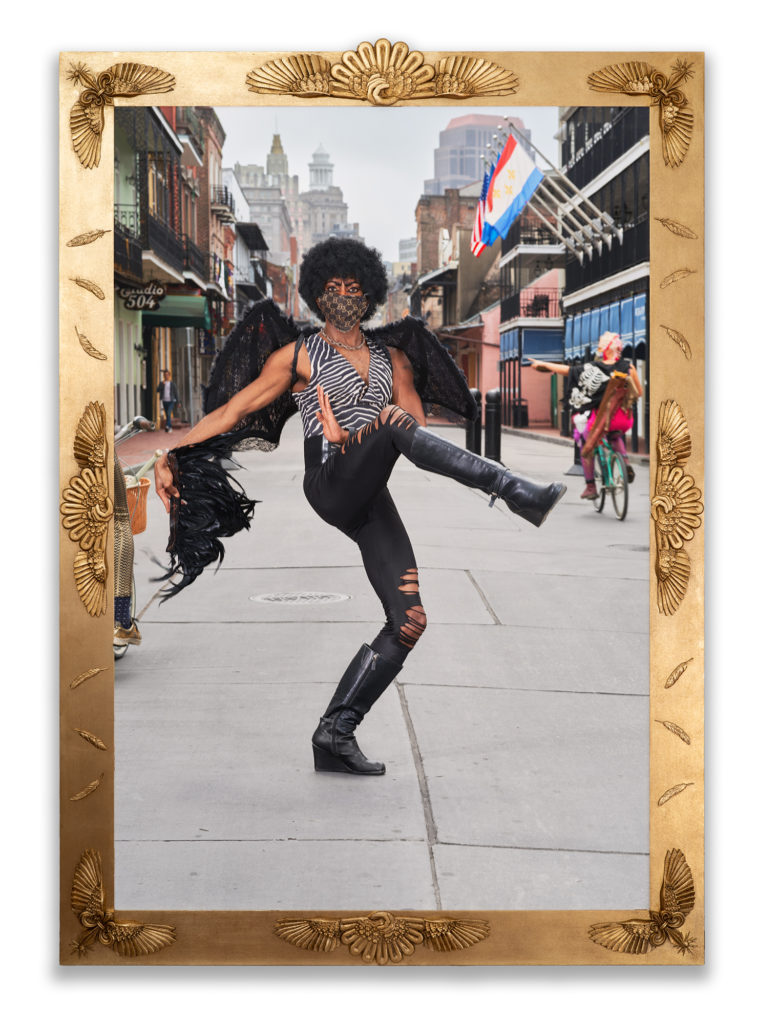

“They’re like gigantic formal portraits of queer society,” says Sean Fader, guiding his laptop through Denny Dimin Gallery in New York City, where he is exhibiting three 4x5ft portraits in regal custom-designed frames. “We’re trained to look at portraits in the Met in these giant golden frames, and learn the way these images are formally meant to be read, but we certainly don’t see queer bodies in those spaces.” Growing up, Fader can only remember mainstream images of “hairless, fatless gay men”, leading him to question what history might look like if the queer community could depict themselves. “I wanted to make a photograph that 12-year-old me could look at and feel empowered by.”

Historically, self-portraiture and activism come hand-in-hand in the world of photography, and Fader wanted to question whether the modern selfie can be considered a form of queer activism. This kind of mutual celebration and interrogation of digital media is a current that runs through his practice — “I love it, but I have a lot of questions for it,” he says. “The advent of digital technology created a space to be seen, but there’s also erasure, marginalisation, and homogenisation that happens as a result. I’m interrogating those things, but also celebrating the ways in which digital technology can be used to forge connections”

For this project, he decided to look at Instagram, where there are currently 42.6 million images hashtagged ‘instagay’. Fader forced his browser to continuously scroll through these images, and asked himself: “What are we trying to say? Are we saying something new? Or are we reinscribing the same violence on our bodies?” These are questions that women have been confronted with for years, says Fader, “but the queer community hasn’t quite yet grappled with the long term effects of normalised media attention”.

The New Orleans-based artist wanted to talk to people in his local area, so he produced an app which scans Instagram for 30 queer hashtags, alerting him when an image is uploaded within a 10-mile-radius. He reached out to these people, asking to meet up and discuss what it means to make a queer image, and what it means to publicly come out using these hashtags. They then worked on a shoot based on this conversation, and the final image is the portrait that his collaborator chose to upload to their Instagram profile.

In the gallery’s front room, these “society portraits” scream queerness loud and proud. The back room, however, is a sobering reminder of the violence that LGBTQ people have faced through history, and which still endures today. Insufficient Memory is a digital installation (also available to view online) which maps LGBTQ murders that occurred in the US in 1999 and 2000 — a window of time that became significant for Fader, in terms of political, digital, and personal history.

“Queer stories are not only erased by lack of media coverage. Queer erasure happens a second round in the advent of digital technology, and our expectations that all histories are digitised”

It all began in 2019, when Fader started a new job as professor of photography at Tulane School of Liberal Arts. His predecessor had left behind piles of obsolete photo equipment, including a Sony Digital Mavica — one of the first commercially successful digital cameras from the late-90s and early 00s. “I had an immediate flashback. My ex-husband’s mother owned one. She was this deep-southern internet junkie who wanted to be like a ‘PFLAG mom’. She would photograph us with it to send to her friends,” says Fader.

Seeing this camera took him back to his own experiences as a queer person in 1999, 16-years before the Supreme Court legalised same-sex marriage in all 50 states. “My ex-husband and I didn’t think we would ever be able to marry,” he says. “Thinking about that 20 years on, it’s a no brainer.” Still, 2019 was the year the Trump administration rolled back an array of protections for transgender people. Holding this piece of technology, which marked the beginning of a mass-democratisation of digital image-making, while thinking about the past 20 years of queer history, sparked an idea.

Fader’s research took him back to 1999, the year after Matthew Shepard, a 21-year-old gay man, was brutally attacked, tied to a fence, and left to die in a field in Wyoming. At the time, federal hate crime legislation only covered race, creed, or religion. Then-president Bill Clinton urged Congress to expand the list to include sexual orientation, but it took a whole decade for the bill to pass, when Obama successfully signed it into legislation in 2009.

Recognising the turn of the century as a crucial time, Fader used a community-compiled spreadsheet to identify LGBTQ people who had been killed in a hate crime in the years 1999 and 2000. There were over 100 names, but for around 80 percent of the cases, he could find barely any information. “I’ve never done a numbers game on this, but you can definitely see that the more affluent, the more white, the more male — those were the stories that were spoken about.” Fader collaborated with multiple people with PhDs in library sciences; sometimes they managed to find a few sentences, other times, nothing. “One of the things that I had to come to terms with was that queer stories are not only erased by lack of media coverage. Queer erasure happens a second round in the advent of digital technology, and our expectations that all histories are digitised.”

The photographer has spent the last year driving over 15,000 miles across 40 states, to visit the crime scene of these murders, documenting them with the Sony Digital Mavica. The resolution is low — “this idea that photography brings visibility, is both a truth and a failure in the images,” says Fader. “It attempts to provide truth, but it fails. Some of the stories that I was able to compile alongside them also lets you know that oftentimes, it was the best I could do.”

The work feels incredibly relevant to this moment in contemporary history, in the midst of the largest movement against racism and police-brutality in US history. “It’s this idea that we can’t let these people be forgotten. We need to hear their names and we need to hear these stories.”

When Fader began making the work, it was 50 years since Stonewall, 20 years since Clinton first introduced a bill to include LGBTQ hate crimes, and 10 years since Obama signed it into legislation. Yet violence against LGBTQ people continues to rise; in the past month alone, five Black transgender women have been murdered in the US, and last year, the American Medical Association declared violence against the transgender community an “epidemic”. In this important time in history, Fader’s work is a reminder that despite recent progress, we must not forget the history of violence, and that the act of remembering is an important part of the continued fight for equality.

Thirst/Trap by Sean Fader is on show at Denny Demin Gallery, New York until 21 August 2020.