by Yohn Yau

May 15, 2016

Judy Ledgerwood discusses her exhibition Far From the Tree in the context of the 40th anniversary of the Pattern and Decoration movement.

Judy Ledgerwood, “Women In A Park” (2016), oil on Canvas, 50 x 60 inches (all images courtesy Tracy Williams) (click to enlarge)

Judy Ledgerwood, “Women In A Park” (2016), oil on Canvas, 50 x 60 inches (all images courtesy Tracy Williams) (click to enlarge)

If, as Amy Sillman has said, “The elephant in the room is sex,” Judy Ledgerwood’s paintings ask the viewer: What exactly do you think you are looking at? The viewer sees a shaped rectangle painted onto an immaculate white ground. A catenary seems to have been used to determine the rectangle’s top curved edge, while both sides bow in slightly, bringing to mind textiles hanging on a laundry line. A few rivulets of paint drip down from the rectangle’s uneven bottom edge. Meanwhile, the thick stretcher bars turn the painting into an object protruding from the wall, rather than a flat thing hugging it.

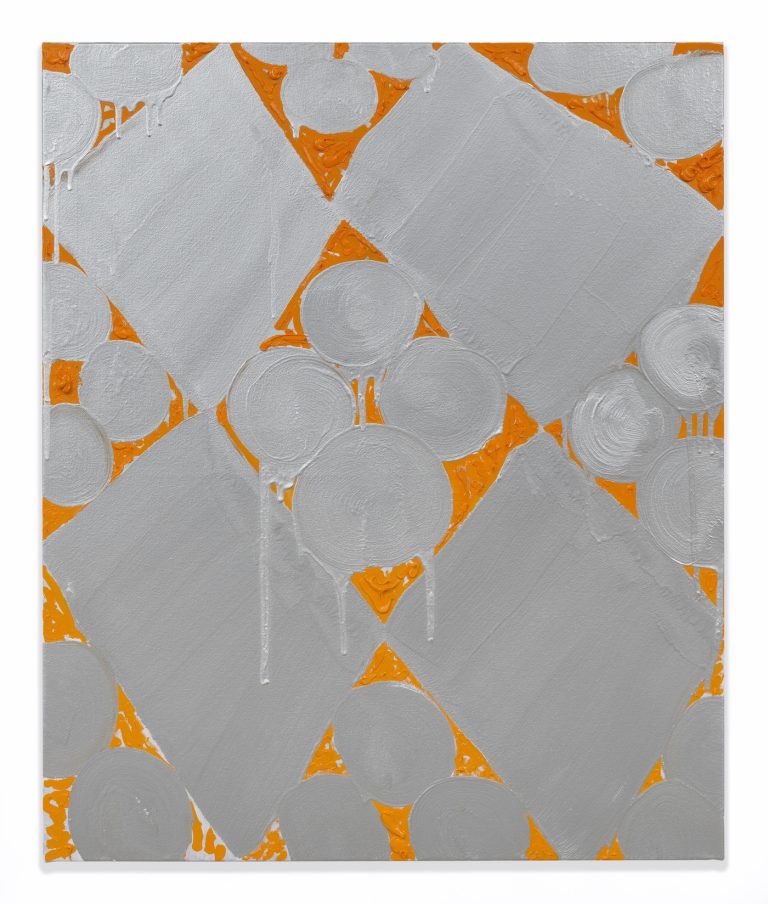

Judy Ledgerwood, “Tangerine Tomorrows” (2016), oil, metallic oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches (click to enlarge)

Judy Ledgerwood, “Tangerine Tomorrows” (2016), oil, metallic oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches (click to enlarge)

In a public conversation I had with the artist the day after her show, Judy Ledgerwood: Pussy Poppin’ Power, opened at Tracy Williams (May 7 – June 16, 2016), it was evident how clearly she had thought about all the issues – including the relationship between painting and architecture – that I’ve just described. Her paintings are what David Reed would call “bedroom paintings.” In her case, this means diamond-patterned grids in which emblems of sexual desire disrupt the comforting visual rhythms we associate with modular units and repetition.

If, as Amy Sillman has said, “The elephant in the room is sex,” Judy Ledgerwood’s paintings ask the viewer: What exactly do you think you are looking at? The viewer sees a shaped rectangle painted onto an immaculate white ground. A catenary seems to have been used to determine the rectangle’s top curved edge, while both sides bow in slightly, bringing to mind textiles hanging on a laundry line. A few rivulets of paint drip down from the rectangle’s uneven bottom edge. Meanwhile, the thick stretcher bars turn the painting into an object protruding from the wall, rather than a flat thing hugging it.

In a public conversation I had with the artist the day after her show, Judy Ledgerwood: Pussy Poppin’ Power, opened at Tracy Williams (May 7 – June 16, 2016), it was evident how clearly she had thought about all the issues – including the relationship between painting and architecture – that I’ve just described. Her paintings are what David Reed would call “bedroom paintings.” In her case, this means diamond-patterned grids in which emblems of sexual desire disrupt the comforting visual rhythms we associate with modular units and repetition.

Judy Ledgerwood, “All the Pretty Ladies” (2016), oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches (click to enlarge)

Another thing about these paintings is their saturated color and tactility, and the dance they engage in. Dark blues, violets, and black dominate the upper two-thirds of “Midnight Garden” (2015), while the bottom row of diamonds, with a green one smack in the middle, suggests a change in the light. In the vertical painting, “Pretty Monster” (2015), Ledgerwood repeats certain colors, such as silver grey, but there doesn’t seem to be any logic to their placement. Or is there? The artist’s ability to walk a tightrope between order and disorder is just about flawless. You think there is no order to the color placement, but then enough doubt creeps in to keep you looking, testing your conclusions, taking the painting apart.

Judy Ledgerwood, “Midnight Garden” (2015), oil on canvas, 84 x 60 inches

If pattern is about seeing the overall design, rather than the particular detail, Ledgerwood pushes in the opposite direction. Her use of color and tactile marks undermines the overall pattern without denying it. A purple triangle flanked by a blue diamond spotted with thick orange circles on one side and a green diamond similarly marked with thick black circles on the other, compels us to examine isolation and juxtaposition, how each color holds its place within the overall scheme.

At the same time, Ledgerwood does something that few abstract painters dare to do: she introduces silly and vulgar possibilities into her work with a rare, debonair lightness. In “Pussy Poppin’ Power” (2016), the artists aligns three vertical rows of diamonds. The ground forthe right and left rows is black, while the middle row is metallic copper. There are four diamonds in each vertical row, with the labial shape drawn in the middle of each one, a number of which appear to have been made by squeezing the paint out of the tube directly onto the canvas. Almost all of the diamonds feature four blots of paint, one in each corner, ranging from thinly painted to thickly applied.

It is in the second diamond down from the top edge, in the row running along the right side, where she does something surprising and – more importantly – inexplicable. Beneath the labial shape she has drawn either a handlebar moustache or the outline of a pair of buttocks. The moustache-buttocks brings us back into the painting, asking ourselves what else has she done that we might not have noticed earlier? What about the pink diamond in the middle row, with its bright red labia outlined in white, sitting right above the shaped rectangle’s drippy, bottom edge? What about the two bottom diamonds in the right row, stacked on top of each other, mirroring each other’s colors? What might that mean?

In the painting, “Women In A Park” (2016), which Ledgerwood told me was her most recent, the shapes collides as if two or more patterns have become entangled with each other. By abutting bands of different colors against the edges of the three triangles anchoring the top of the painting, the artist shifts our perception of the diamonds from flat shapes to volumetric forms, and back. Again, the artist is masterful in her ability to poise the painting between order and chaos without one superseding the other. If the other paintings in the exhibition are bedroom paintings, “Woman In A Park” comes across as more public. Suspended between stability and pandemonium, it reminds us that any tidiness that we achieve in life, any sense of a routine that can be counted on, is an illusion. Interruptions are bound to happen.

In Ledgerwood’s paintings the viewer encounters elements of humor, instances of surprise, celebrations of female sexuality, forms of vulgar tactility, and intense and unpredictable combinations of color. There is nothing formulaic about her approach, which distinguishes her work from many other contemporary abstract painters as well as those working with pattern and decoration. Most of all, she brings these disparate possibilities into play in her work, which doesn’t look like anything else being done. Henri Matisse was genteel in his depictions of odalisques. Ledgerwood lets us know that the elephant in the room was more than just sex.