In Literature, Who Decides When Homage Becomes Theft?

Appropriation goes both ways, and increasingly it’s being seen as a creative freedom for writers who have been excluded from the literary canon.

By Ligaya Mishan

Oct. 8, 2018

IN JANUARY, the critic and novelist Francine Prose took to Facebook to express her outrage at a short story in the latest issue of The New Yorker by a relatively unknown writer named Sadia Shepard. Second-guessing The New Yorker’s fiction department is something of a parlor game among members of the literati, but Prose wasn’t interested in quibbling over aesthetics. To her, the story, titled “Foreign-Returned,” about Pakistani expatriates adrift in Stamford, Conn., was a flagrant rip-off of Mavis Gallant’s “The Ice Wagon Going Down the Street,” about Canadian expatriates adrift in Geneva, Switzerland, and also published in The New Yorker, in 1963. “It’s just wrong,” Prose declared, setting off a skirmish on social media that rallied other acclaimed writers, including Alexander Chee, Jess Row, Gina Apostol and Salman Rushdie, to Shepard’s defense.

Six years earlier, a similar scenario of influence and homage had unfolded, also involving two stories published more than half a century apart, also both in The New Yorker, because the literary world is that small. (Full disclosure: I was once on the magazine’s editorial staff, but not when any of these stories appeared.) “Referential,” by the short-story master Lorrie Moore, opens with two people fretting over what birthday present to give a deranged and hospitalized young man and ends with the hollow ring of a telephone — the same trajectory traced by Vladimir Nabokov’s 1948 “Symbols and Signs” (later retitled “Signs and Symbols”). Like Shepard, Moore diverges from her source in details but cleaves to its structure so closely that the likeness is undeniable. Yet Moore received no public censure, no scolding from a critic of Prose’s stature and power. For the same act, one writer was called out, the other given a pass.

Neither was trespassing. There’s long, honorable precedent for revisiting and recasting the work of fellow writers, communing and wrestling with predecessors and contemporaries alike; it’s essential to art as a sustained exploration of the human condition over time. So why the imbalance in response? Perhaps, paradoxically, Moore’s take on Nabokov seems more “acceptable” precisely because she doesn’t stray too far from the original, doesn’t subvert it, but simply and deftly applies a light, modern gloss with her incisive observations of domesticity and her trademark mordant wit. Her characters — white, educated, middle-class — are readily identifiable as part of Western literature, possessing their leading roles as if born to them. Shepard’s are not: They’re drawn from her background as the American-born daughter of a white father and a mother who was both Pakistani, with roots in a country once colonized by and subordinate to the West, and Muslim, part of a group increasingly demonized in today’s political rhetoric. Shepard’s approach to Gallant, and the Western literary tradition, is thus more radical. As an outsider, she is refusing to “know her place” on the margins and is instead writing herself into the canon, making — taking — a space where none might otherwise be granted.

IN PROSE’S INDICTMENT of “Foreign-Returned,” she never used the word plagiarism, but on Facebook, she dismissed the story as a “copy,” and in a letter to The New Yorker, she raised the specter of copyright laws. So the accusation is implicit.

The root of “plagiarism” lies in the Latin plagium, defined in Roman law as the crime of kidnapping, specifically enslaving free citizens or seizing and extorting labor from someone else’s slaves. Plagium in turn is believed to derive from the Latin plaga, which can signify either a snare or the stripe on skin called up by a whip, the presumed punishment of plagiarii. Only in the first century A.D. was the term deployed, by the poet Martial, to highlight a false claim of authorship. Later, it became a specific reference to the abduction of children, and is still cited as such in Scottish law, while another derivative, plagio, formerly a statute in Italian law, is loosely translated as brainwashing: the subjugation of another’s mind, bending it to one’s will.

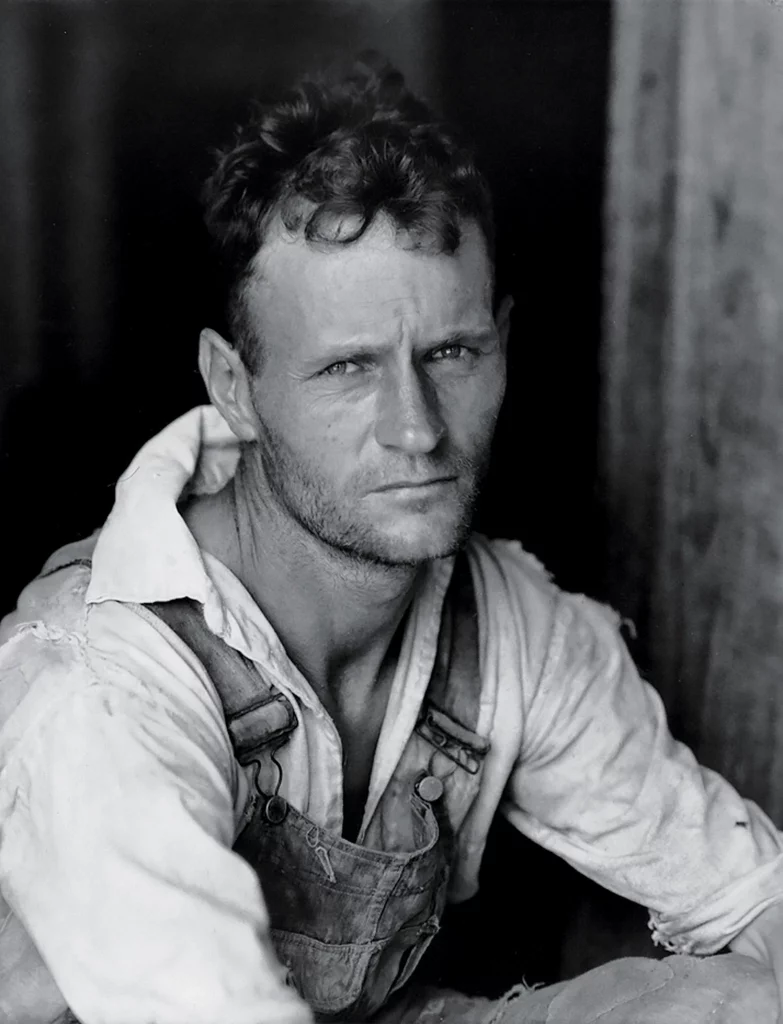

This etymology suggests that an author’s inventions are as precious as human lives and liberty, and that his preciousness is literal, in the sense of lost property. Martial was speaking of verbatim theft of entire verses, however, and what constitutes plagiarism today, in literature, music or the fine arts, is rarely so clear. The Scottish artist Douglas Gordon’s film “24 Hour Psycho” (1993) is materially the same as Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” (1960), except run in ruthlessly slow motion, silent, attenuated and sapped of drama, forcing the audience to project and manufacture meaning. The Norwegian artist Leif Inge did a similar experiment, titled “9 Beet Stretch” (2002); in each case, “stolen” goods — for Inge, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, stretched from about 70 minutes to a somnambulantly majestic all-day affair — were rendered unrecognizable. A more confrontational encounter between past and present took place in 1981, when the American artist Sherrie Levine exhibited what appeared to be Walker Evans’s Depression-era sharecropper portraits — in fact, photographs she had taken of reproductions of the originals — and labeled them her own work, both challenging the notion of authenticity and questioning the transformation of impoverished lives, via art, into a commodity. Her prints wound up in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s permanent collection. In 2001, another American artist, Michael Mandiberg, scanned the same Evans images that Levine had used and made them publicly available as online downloads, each accompanied by a “Certificate of Authenticity” attesting to authorship: Mandiberg’s.

Michael Mandiberg’s appropriation of Sherrie Levine’s appropriation of Walker Evans.

Credit: Michael Mandiberg, “Untitled (aftersherrielevine.com/1.jpg),” 3250 px x 4250 px (at 850 DPI), 2001.

In 2010, the German writer Helene Hegemann, then 17 and a child of open-source culture, bred on sampling, remixes and mash-ups, was baffled to be charged by critics with plagiarism for incorporating lengthy unattributed passages from a German blogger known as Airen (as well as from sources as varied as the French literary theorist Maurice Blanchot and the ’60s British band the Zombies) into her debut novel, “Axolotl Roadkill.” “There’s no such thing as originality anyway, just authenticity,” she wrote in a statement to the press. (Attributions were nonetheless appended to subsequent editions.) That may sound like pirate talk, but nearly a century and a half earlier, Brahms had much the same response when asked whether he’d pinched Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” theme for the finale of his First Symphony — “Any ass can see that” — and Hegemann was merely echoing Ecclesiastes 1:9, which was written more than two millenniums ago: “There is no new thing under the sun.” Stealing is better than imitating, as T.S. Eliot once wrote (and as numerous writers on the subject of plagiarism have quoted him). But intent and execution matter, he went on: “Bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.”

IN “THE ICE WAGON Going Down the Street,” Gallant’s central character, Peter, is a man of pedigree from Ontario, whose surname has the chime of money and whose faith in his capacity for victory rests on his father’s conviction that “nothing can touch us.” With his patrimony frittered away by the previous generation, however, he must take a dull clerk’s job in Geneva, which he silently revolts against by “strolling to work as if his office were a pastime and his real life a secret so splendid he could share it with no one except himself.” His wife, Sheilah, supports him blithely, haunting the story as a kind of vague shimmer on the sidelines. But Peter’s lack of momentum is challenged by Agnes, his ambitious and prim young female office mate and a fellow expatriate Canadian, who on her first day at work hangs her framed college degree on the wall — an act of pride that, to him, betrays “push, toil, and family sacrifice” and her “inferior” origins as a child of immigrants from Norway: “He would not have invited her to his house except to mind the children.” At a party, she gets drunk, despite her religious convictions, and Peter has to escort her home, leading to an unexpected, inchoate intimacy. He has a slow-moving premonition of disaster (“a railroad bridge over an abyss snapped in two and the long express train, suddenly V-shaped, floated like snow”) and retreats. When they next see each other at work, Agnes reveals her disillusionment with Peter and his “educated,” amoral crowd, meandering through unearned lives. Soon after, Peter and his wife leave Geneva, still convinced of their shining future, which never comes to pass.

Shepard’s aim in “Foreign-Returned” is not to write over Gallant’s story, as in a palimpsest, but to write alongside it; to tilt the lens to take in the people kept offstage at the time Gallant’s story was set, like the Pakistani sociologists, mentioned only in passing, who supplant Peter and Sheilah as guests at their wealthy white friends’ summer home, or the Muslim refugee child who appears, weeping, on their friends’ Christmas card. Here the heir to Peter’s melancholy abeyance is Hassan, an unaspiring analyst from Karachi. In Pakistan, he and his wife, Sara, grew up in ancestral homes and “had histories that were understood by their friends, shared by their neighbors,” but in Connecticut, they were “inconsequential.” Where Peter and Sheilah never allow themselves to doubt their own worth, Hassan and Sara perceive their diminishment and are estranged by it: She tries to fake her way up the social ladder, and he comes perilously close to publicly exposing her lies.

Gallant’s story begins at the end, with Peter’s failure, and circles back, as it seems Peter will spend his whole life doing, sifting through memories for the moment when everything was lost. For Shepard, the narrative belongs as much to the women in Hassan’s life, Sara and his office mate, Hina, who appears in the urgent present of the story’s opening line. Hina shares Hassan’s ancestry but grew up in the United States. He’s annoyed that they’ve been teamed up, “the two Pakistanis,” he thinks, lumped together, when in his eyes they have little in common. Her parents are uncosmopolitan, immigrants from “the kind of second-tier industrial city you visited only if you had a specific reason,” and he recoils from her “high and mighty” religious fervor. (She arrives at the office armed with her Quran, prayer rug and hijab.) In her meticulousness, he sees a rebuke: “That’s why American Pakistanis like me are superior to Pakistani Pakistanis like you.” At the same time, Hassan has trouble finding kinship with other Pakistani expatriates. Posh Lahoris whom he and his wife had considered friends gently elbow them off their guest list by telling them that their new “multicultural” book club has room for only one Pakistani couple — a winking allusion to the limits of minority representation in America.

In “The Ice Wagon,” Peter’s inability to anchor himself becomes a reflection of postwar malaise. “Foreign-Returned” unfolds amid the anti-immigration fervor of the 2016 presidential election and is suffused with a more immediate sense of threat. Hina confides in Hassan that she was harassed by a white man while canvassing for voters in Pennsylvania; he’s infuriated on her behalf, abruptly becoming her ally. Later, when she feels sick at a party — after some older Pakistani women badger her to take off her hijab for a matchmaking photo — he’s appointed to accompany her home and ends up inside her apartment. In her anger at herself for believing in the superiority of “educated Pakistanis” like those at the party (and, by extension, Hassan), Hina unpins her head scarf, unfurling her hair before him in a shocking act of intimacy. The next time they meet, she confesses that she has not spoken to her parents in five years, since they tried to marry her off and she refused. This is the grief that propels her, a grief wholly alien to Hassan, who cannot imagine such a severance: He “had always been aware that he might lack the qualities essential for success in America, but it had never seemed as evident to him as it did now.”

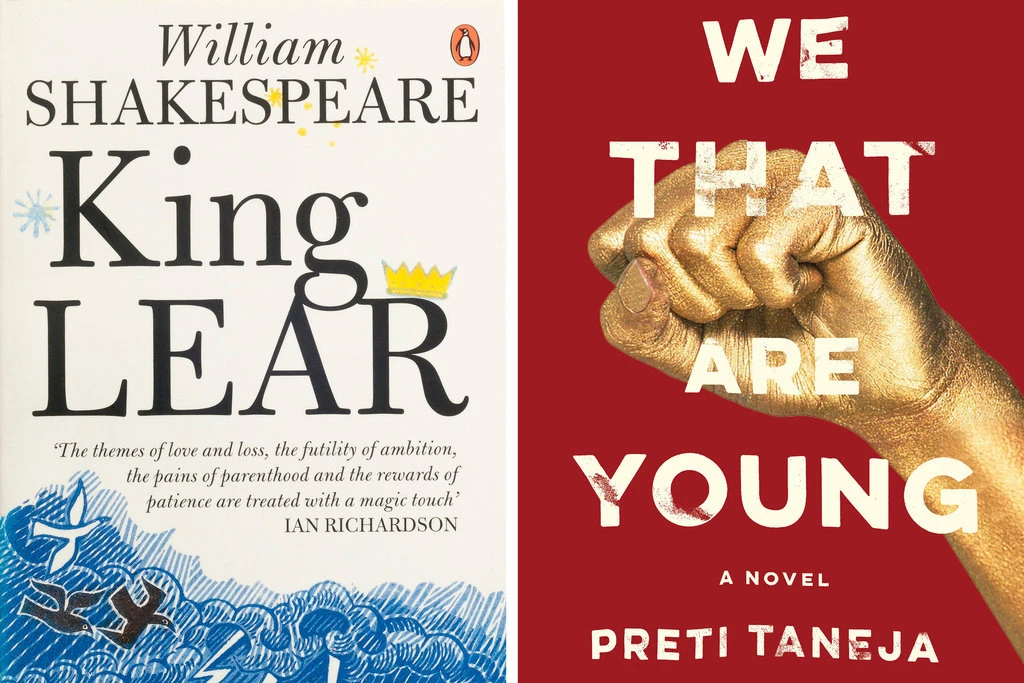

The British-Indian writer Preti Taneja’s novel “We That Are Young” was recently released in the United States, wrenching “King Lear” out of Iron Age Britain and setting it ablaze in a modern, feral New Delhi and a shattered Kashmir.

Shepard’s story ends on a note of resignation. Hassan and Sara have returned to Pakistan, where they genially recall a sun-burnished Connecticut that never was, while Hassan tries to picture the younger siblings whom Hina left behind, wandering their American living room, “content in their kingdom,” before the Old World and its ancient demands intrude. It’s a quiet, contained close to a story of unarticulated and unrealized wants. In “The Ice Wagon,” Peter and Sheilah have likewise returned to their home country, none the better for their travels but heroically oblivious to their defeat. Only in the final moments do we get a glimpse of Peter’s isolation, as he swerves into a vision of solitude at once serene and terrifying, of waking up early in the morning and running out, alone, to meet the ice wagon coming down the street — a vision borrowed from Agnes (as Shepard, decades later, will borrow from Gallant): “He has taken the morning that belongs to Agnes, he is up before the others, and he knows everything. There is nothing he doesn’t know.”

TO BE CALLED a plagiarist is arguably the most profound and existential accusation a writer can face. For a plagiarist is no longer considered a true writer, just a cribber peeking over a smarter classmate’s shoulder. Some so accused have never recovered, as Gina Apostol notes in her critique of the Shepard-Prose conflagration in the Los Angeles Review of Books, including the midcentury Filipino-American writer and labor activist Carlos Bulosan and Nella Larsen, who came to fame during the Harlem Renaissance. Bulosan was able to publish only a few stories after charges were made, and Larsen none.

Notably, Shepard and Moore are not the only fiction writers published in The New Yorker in the past decade who have made tributes to writers past. The Nigerian-American Chinelo Okparanta modeled her 2013 story “Benji” after the Canadian writer Alice Munro’s 2010 “Corrie”; Yiyun Li, a Chinese-American, took inspiration for “Gold Boy, Emerald Girl” in 2008 from the Irish writer William Trevor’s “Three People,” published in The London Magazine in 1998. Perhaps The New Yorker is trying to tell us something about the importance in our divided times of crossing borders, of finding both the individual and the universal in lives separated by geography, culture and time.

This was cultural appropriation in its earliest, positive sense, as used by sociologists in the 1970s to identify how groups outside the mainstream borrow from the presiding culture and make it their own. Now cultural appropriation is wielded as a pejorative against writers and artists who draw material from the trauma of those less privileged than themselves. In July, the white French Canadian theater director Robert Lepage was confronted with protests over two productions that explored the subjugation of nonwhite peoples: “Slav,” based on African-American slave songs, and “Kanata,” an account of the suppression of indigenous Canadians. Both shows were canceled. Around the same time, The Nation published a poem by Anders Carlson-Wee, the white son of Lutheran pastors in Minnesota, in which he attempted to ventriloquize a homeless person with a clumsy mimicry of black dialect. After an outcry, the magazine’s poetry editors issued an apology, saying that they had “made a serious mistake” in giving a platform to such “disparaging” language.

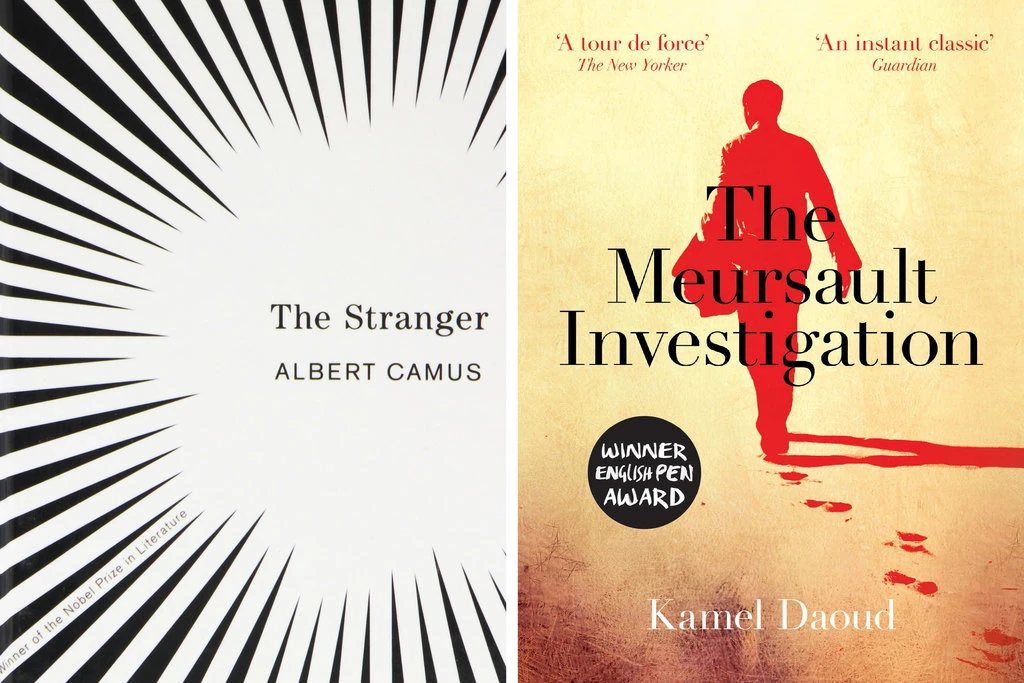

The Algerian writer Kamel Daoud’s novel “The Meursault Investigation” (2013) gives a name and history to the anonymous Arab victim in Albert Camus’s “The Stranger” (1942).

The Algerian writer Kamel Daoud’s novel “The Meursault Investigation” (2013) gives a name and history to the anonymous Arab victim in Albert Camus’s “The Stranger” (1942).

Inevitably, the backlash against each work of art was followed by a backlash against the backlash, and rumblings about censorship. But those fighting most fervently for and against cultural policing missed the central point. Lepage’s productions drew ire for bypassing black and indigenous peoples — their ostensible subjects — in favor of nearly all-white casts, and Carlson-Wee’s poem was a well-meaning but naïve portrait of homelessness that reinforced rather than interrogated stereotypes. The issue isn’t the right of artists to imaginatively enter other lives. What’s being questioned is the concentration of cultural capital, and how members of the dominant class, who tend to receive more resources and broader access to the public, are rewarded for telling “difficult” stories — like those dealing with the subjugation and suffering of minorities and the poor — even when they misrepresent the people they’re claiming to speak for. Often theirs are the loudest, if not the only voices heard on the subject. No one should proscribe artists from trying to transcend the limits of their experience; the joy of art and literature has always been how they free us from those limits. The answer is not to have fewer stories, but more.

GALLANT’S STORY IS great. And Shepard’s story, whether readers consider it the equal of its inspiration or not, is worth hearing. It brings her into a literary conversation that has not traditionally put people like her at the fore. In this, too, she is following others’ lead, like the Welsh-Creole writer Jean Rhys, who placed Bertha Mason, the madwoman in the attic of Charlotte Brontë’s “Jane Eyre” (1847), at the heart of “Wide Sargasso Sea” (1966); the Sudanese writer Tayeb Salih, whose novel “Season of Migration to the North” (1966) reversed the arc of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” (1899); and the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud, who in his novel “The Meursault Investigation” (2013) gives a name and history to the anonymous Arab victim in Albert Camus’s “The Stranger” (1942). In August, the British-Indian writer Preti Taneja’s novel “We That Are Young” was released in the United States, wrenching “King Lear” out of Iron Age Britain and setting it ablaze in a modern, feral New Delhi and a shattered Kashmir. Her landscape bristles with ghosts, Shakespeare flickering in an eerie déjà vu. The bones show through, and the book is all the fiercer for it.

“To steal a book is not a theft,” pleads a drunk, starving scholar in the Chinese writer Lu Xun’s 1919 short story “Kong Yiji.” The sad-sack character, having failed the official state exam, has no means of making a living, so he swipes books and sells them in order to buy wine. His defense hinges on a shift between two distinct words for “steal,” one elevated, one vernacular; accordingly, the phrase is sometimes more aphoristically translated as “to steal a book is an elegant offense,” in which form it has been misapprehended by the West as ancient Confucian wisdom. The original joke is that the difference is entirely semantic: Theft is no longer theft if you use a more beautiful word. But is it a joke? Writing, after all, is about choosing one word over another. “Purloin,” “burgle,” “filch,” “steal”: Pick one and the dominoes fall, affecting every word that follows. Somewhere a butterfly flaps its wings. The story changes.