Querying the New Appropriation Art: Is this Cynicism?

By Joseph Henry, January 8, 2015

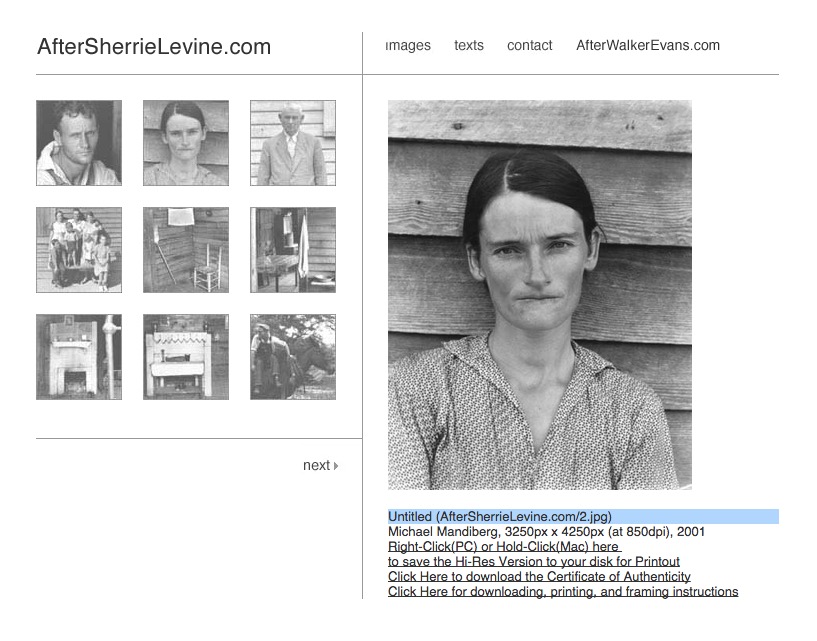

Michael Mandiberg, “After Sherri Levine,” 2001.

The Denny Gallery may have given themselves a curatorial headache with the title of their current exhibition, Share This! Appropriation After Cynicism. There are more tricky connections and presumptions in that moniker alone than in the web mantras and second-person addresses that typically sign most contemporary shows. To begin, the title suggests there was an appropriation art of cynicism. To most eyes, the “cynical” historical referent would be the founding generation of “appropriation art,” the New York Pictures Generation. The list of names in that canon could fill (and have already) their own museum wing: Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Laurie Simmons, Sherry Levine, Sarah Charlesworth, Louise Lawler, James Casebere, et al. One hopes Denny makes such a historical claim in their title with a degree of caution. To assemble these artists under an affective genre of cynicism would unfairly reduce the aesthetic particularities of their respective corpi and rob the political, usually feminist, component of its historical import.

Then what is the new, “sincere” appropriation and what was wrong with the old one? The clue lies in the exclamatory clause of the exhibition title: sharing. As the gallery press release clearly states, Share This! displays the work of “artists who appropriate the work of other artists.” If the Pictures Generation mined advertisements and Hollywood films for their source material, the new appropriators look to each other for content. This distinction seems to have become more calcified with age: despite the vanguard’s analyses of representation and commodity semiotics, they are distinctly authorial figures: for a generation of artists concerned with overthrowing standard notions of creativity and originality, their practices are decidedly and institutionalized – and expensive. No one’s confusing (or selling) a consumer-grade copy of a Cindy Sherman for an authenticated equivalent. The artists at Denny, then, have a different relationship to the market and ostensibly, to each other. Sharing is caring.

What exactly is so “post-cynical” about the work of Share This! remains an open question, a deficit reflective of the exhibition’s multivalent if not entirely elaborated conceptual premise. Not only does little of the art on display offer a decidedly emotional reading, but the feelings they might generate hardly speak to the utopia of life after cynicism: the artists here, to the show’s credit, steal, lie, mimic, and plagiarize in a social world more complicated than just smiles and helping hands. Share This! offers little resolution to these questions, which, let it be said, aren’t entirely novel: in a 1982 essay titled “Appropriating Appropriation,” the critic considered most adjacent to appropriation art, Douglas Crimp, acknowledged that “appropriation, pastiche, quotation – these methods extend to virtually every aspect of our culture.”

What’s new is the alacrity and ease with which appropriation can occur on a mass level. The obvious historical paradigm shift between late and high appropriation is the changed technologies: image duplication and distribution. Michael Mandiberg took this head-on in 2001, in the visually humble installation After Sherrie Levine, revived here for the Denny show. Visitors are invited to download a file of Levine’s canonical After Walker Evans, already a copy of another photographer’s work and then reproduce it from a nearby printer alongside a certificate of authenticity. The punch line is Crimp’s essay title. Mandiberg’s installation works as a historical precedent for Share This! and though its very historicity speaks witness to the pace of changing attitudes toward image copying, its premise now rings hollow. The infinite regress of appropriating appropriation is obvious, but what demands a more canny observation is how a print-out of a Levine is definitely not a Levine. The tautological relationship between original and copy, perhaps nascent in 2001, requires a more agile analyst of image economies in 2015 – I think of Hito Steyerl’s investigative, shrewd film essays, for instance.

A slightly more contemporary, and thus savvier, dramatization of appropriation is the exhibition’s only substantial nudge at its title’s good feelings. For a performance last year at both PULSE and SPRING/BREAK art fairs, Sean Fader asked passers-by to whisper a wish into his ear, stroke his chest hair, and document the experience on Twitter, Instagram, etc with #wishingpelt, in reference to the artist’s hirsuteness. Richard Prince, influential contemporary-artist-turned-professional-internet-troll, reproduced an image of Fader and a wishing participant for his infamous Gagosian exhibition of Instagram uploads. At Denny, Fader mounts the blown-up ‘Gram with a new image captioned, “Our pictures are for each other: #wishingpelt #collectiveauthorship #artselfie,” the notion being that gallery visitors reduplicate the experience with a selfie next to a selfie.

Fader, who’s present at the gallery most days to assist with the auto-portraiture, enacts the sharing and caring of the exhibition’s title: the optimistic desires of his original performance, based admittedly on a quirky kind of eroticism, necessarily requires its distribution online and on the gallery wall (a counterpoint here is the more enclosed intimacy of the late Adrian Howells’s work). I’m not sure the hashtag is an instrument of collective authorship, as much as it is currency for a corporate-minded smart-phone app. But in topping up Prince’s own appropriation of the performance, Fader shapes a dialogue on display value and contemporary strategies of (self)-promotion. His connections between the sentimentality of the wish, the attention of the hashtag, and the creativity of the artist are fertile in their implications, if perhaps naïve in their politics.

But both Fader and Mandiberg teach a primary lesson of appropriation art; the narratives surrounding appropriation, who takes what from who for what, are often far more curious than the aesthetics of the object itself. Artists in Share This! who don’t convey the complexities of their appropriative networks, like Matthew Craven and Jordan Tate, lose conceptual weight for a scrapbooked, blandly pastiche aesthetic.

Crucial here, then, is a display strategy that performs the networked nature of appropriation art, something that makes me want to know the story behind the object (relegated to press material and a gallery attendant, in this show’s case). Adam Parker Smith, for example, re-enacts, in part, Thanks, a 2013 exhibition at Lu Magnus wherein Smith assembled and sometimes sold works stolen from studio visits with other artists. At Denny, a sampling of the objects is presented with its components exchanged for others throughout the duration of the show. Thanks hits on the contemporary vogue for the archive no doubt, but it’s an archive composed with emotional tones of betrayal, camaraderie, and collaboration. None of the artists objected to Smith’s thievery and at Lu Magnus, he often sold their work for them. In a similar case in Share This!, Ana Teles riffed on objects made by colleagues under preparation for an MFA crit, copying and modifying them for her variations as she saw fit. Smith, and to a lesser extent, Teles, externalize the concatenation behind artistic influence that requires some plagiarism, some originality, and constant interaction.

What Share This! does best is illustrate a microcosm of the relationships between artists not yet at blue-chip-level incomes, especially in an environment as simultaneously hostile and supportive as New York. Many critiques of the neoliberal economy have identified “the artist” as the frightening paradigm of new kinds of labor – underpaid, stripped of benefits, and supported by the attritional pursuit of one short-lived opportunity after another. Taking stock of the networks between working artists, then, is a crucial task. The historicist examples of appropriation art in the exhibition differ little in tactic from their precedents thirty years ago (like artists in Share This! quoting from antiquity or neoclassical sculpture). Yet Denny’s exhibition puts together a useful micro-history of new appropriation art that highlights myriad responses to current social exigencies. What demands emphasis is not the sharing and sincerity among acts of appropriation, but the sharing and sincerity among appropriators themselves.